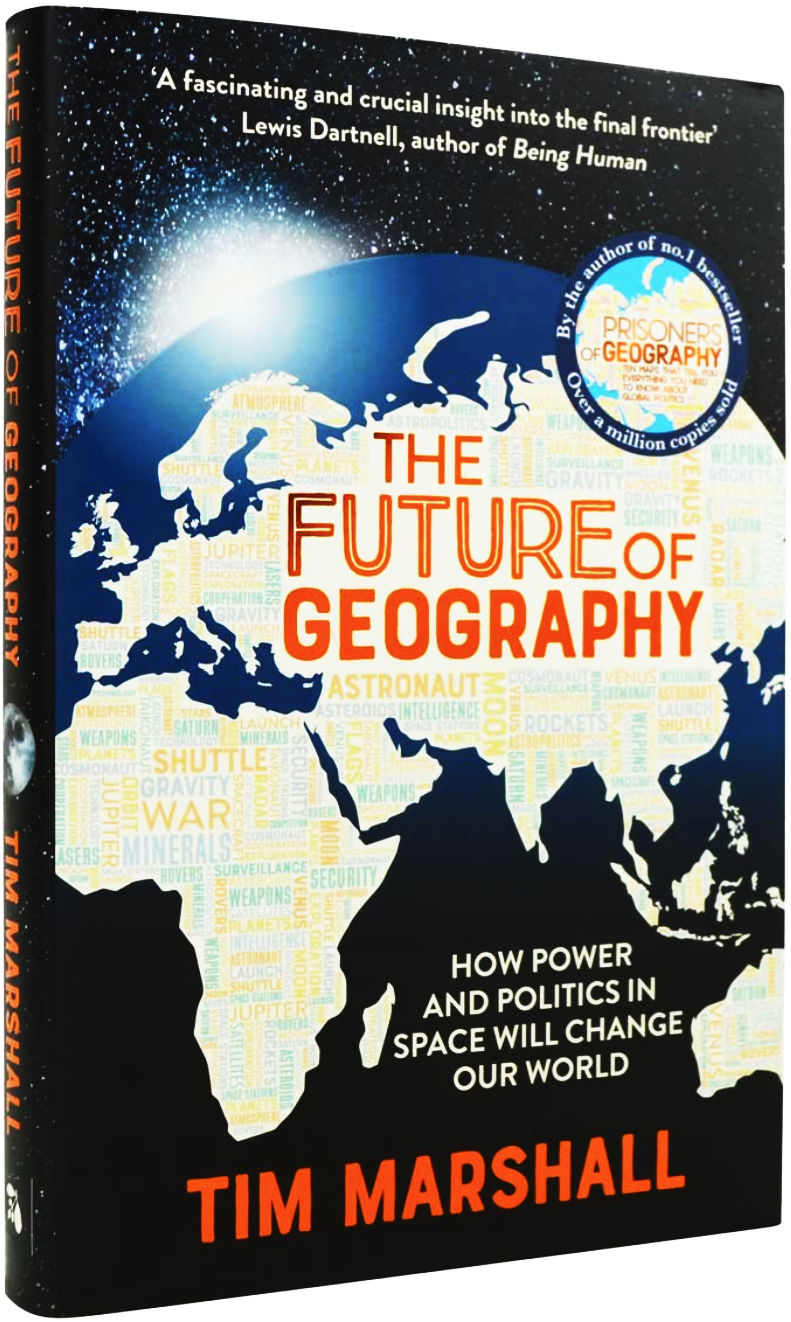

Book Review: The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change Our World

Tim Marshall

May 2023

Tim Marshall predicts that humanity’s search for resources will soon extend beyond Earth, with the moon as a staging post. The Future of Geography is a useful introduction to astropolitics.

Earth, with the moon as a staging post. The Future of Geography is a useful introduction to astropolitics.

Whether it is Elon Musk’s SpaceX launching reusable rockets to put thousands of Starlink satellites into orbit or the emerging competition for resources on the Moon that pits the US and China against each other, space exploration and satellite technologies are back in the news in a way not seen since the late 1960s. Besides those big players, more than 80 countries, including ones in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, now have a presence in space and a national space programme.

This book is journalist and author Tim Marshall’s third book on the future of geography, but on this occasion, he explores the future of geography – the geography beyond earth. As a non-expert, Marshall does a good job of explaining ‘Astropolitics’ to those who know little about this new emerging field which Marshall believes will be part of the next generation of great power competition.

Marshall charts the human fascination with the stars from hunter-gatherer tribes to the present day, through the Babylonians and Sumerians, the Greeks and Romans, and the Golden Age of Islam. He tracks the development of scientific exploration through the familiar names of Copernicus, Giordano Bruno, Galileo Galilei, Newton and Einstein, and emphasises that the knowledge of the past has been surprisingly accurate in its measurements of the Earth and its place in the stars.

It was the Russians who initially took the lead, much to America’s chagrin, and Marshall reminds us that Russia actually reached the Moon first. The Americans caught up, but Marshall reminds us that “Armstrong is a colossal figure, but he knew he stood on the shoulders of giants such as Gagarin and Tsiolkovsky, Goddard, Oberth, Korolev, von Braun and, before them, the great scientists down the ages.”

Marshall acknowledges the reasons for the space race coming to an end when it did was due to budgets and political pressures, but it is now over 50 years since humans have walked on the Moon and Marshall explores the question — is it now time to go back?

Marshall explores the reasons for countries and ‘space superpowers’ to go back to the Moon. He compares space geography to Earth geography and observes that if an interested party controls access to a place — terrestrial or otherwise, then they have the power there: “If a space superpower could dominate the exit points from Earth and the routes out from the atmosphere, it could prevent other nations from engaging in space travel. And if it dominates low Earth orbit, it could command the satellite belt and use it to control the world.”

Marshall outlines that our oldest satellites contain an abundance of resources, not least Helium-3, the fuel for a potential future fusion reactor. Investment possibilities in the minerals of the Moon and beyond might prove to be the lure we can’t resist. “Many countries have the incentive to go after them [metal oxides], especially those that don’t want to rely on China, which currently holds a third of the world’s known reserves.” Due to this Marshall believes we need an understanding of geopolitics and ‘astropolitics’ is also required in space, as our expansion continues. “Many of us still think of space as ‘out there’ and ‘in the future’. But it’s here and now — the border into the great beyond is well within our reach.”

Marshall repeatedly makes the call for global cooperation as an approach through which space exploration can continue in a positive manner. Without global cooperation, Marshall’s fear is that “…we may end up fighting over the geography of space, just as we have done over the geography of Earth.” The current legal frameworks and agreements that do exist, Marshall believes, rely on countries signing up to them and some of the definitions are too loose and hazy to be effective. Marshall explores hypotheticals that need addressing before they happen, not as a belated response after the fact.

Marshall dedicates a whole chapter each to the ‘big 3’ space superpowers: China, the US and Russia, and highlights their respective notable achievements and ambitions for space activity. China, he believes, is the least-credited space explorer: “In 2019,…” Marshall explains “…the uncrewed Chang’e 4 became the first spacecraft to land on the far side of the Moon. In a perhaps now expected symbolic tradition, it planted the Chinese flag on the surface and began digging for rocks in a region it is considering using as a base.” The US “…plans to construct a Lunar Gateway Space Station near the Moon,” and Russia is developing a new system known as Kalina, which could focus laser beams to dazzle or ‘blind’ other orbiting satellites, in actions that might normally be seen in a James Bond movie.

The big three no longer have space to themselves. A growing number of countries and companies are trying to elbow their way into the new world of space exploration. Jeff Bezos has founded Blue Origin, Richard Branson has Virgin Galactic, and Elon Musk has SpaceX. In addition, there are a host of countries, including France, Germany, Japan, Australia, the UK, Israel, Iran, India and the UAE, who are all vying for projects, partnerships and prestige in an increasingly crowded marketplace.

“Each time humanity has ventured into a new domain,” Marshall concludes, “…it has brought war with it. Space is no different and the potential battlefield is beginning to take shape.” Given our history, he feels, “…it is unlikely that we will recognize our common humanity and work together in space to harvest its riches and then distribute them equally.” At the same time, he accepts the inevitability of our next steps into space: “Humanity has not gone so far only to stand still now.”

Marshall believes by the mid-2030s — only a short 15 years from now we may see the first human landing on the planet Mars. Marshall believes it’s worth taking a moment to imagine that. How many people across the world will watch this global event, if and when it happens? Which country or group of countries or even group of companies will put the first person on Mars?

The future of geography provides a useful past, present and future on astropolitics. For those who follow geopolitics and global competition, this is a growing area and compulsory reading for students, activists, professionals, and everyone who wants to make sense of the world. Going forward it may very well be events in space shaping events on Earth. Tim Marshall’s book is a good place to start making sense of this.