It is often said that it helps to have friends in high places. Israel, long the beneficiary of bipartisan support in Washington, enjoys more than its fair share of friends in high places —from congressional backbenchers to the upper echelons of the Pentagon, Israel has them all. But even the closest of allies cannot always protect a nation from its own strategic misdemeanours.

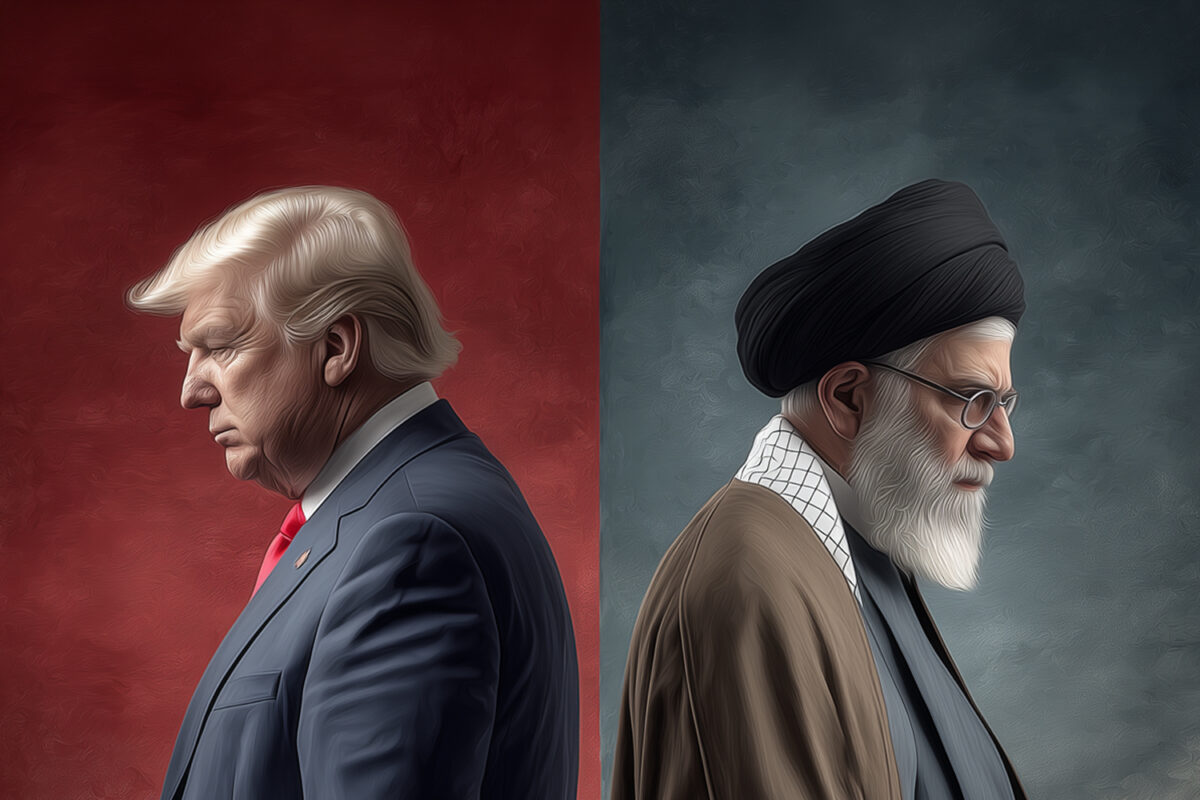

The latest round of hostilities in the Middle East has exposed a set of inconvenient truths. Chief among them is that America’s support, while considerable, is ultimately transactional. Grand talk of shared values and “ironclad commitments” may fill press briefings and prepared speeches, but when interests diverge, sentimentality gives way to ground realities and vested interests. Even Israel, often regarded as the cornerstone of the Western strategic presence in the region, must bend to its master’s will.

That fact has been made painfully clear in recent weeks. Israel, perhaps emboldened by its perceived indispensability, assumed that the United States would intervene quickly and decisively to halt Iranian reprisals following its aggressive military actions against Iran. To the indignation of the Israelis, when the President of the United States says that attack on US bases and personnel will elicit a response, it tacitly gives the green light to the Iranians to strike Israel with whatever it has without fear of attack.

Iran, meanwhile, wagered that Washington would restrain its attack dog and curb Israeli ambitions. Both were mistaken. The result is an escalation in which neither side has achieved its strategic objectives—and both have exposed their vulnerabilities.

Israel’s aura of invincibility, so carefully cultivated since 1967, has suffered a blow. Though its initial strikes degraded Iranian air defences and targeted key nuclear facilities, they stopped short of crippling Iran’s nuclear infrastructure. Iran, despite suffering early setbacks, recovered quickly and has continued to launch missile barrages against Israeli targets with an alarming frequency. That these missiles penetrated not only Israeli defences but also those of its regional allies such as Jordan and the US has unsettled defence planners in Tel Aviv and beyond.

Israel’s aura of invincibility, so carefully cultivated since 1967, has suffered a blow

Israel’s much-vaunted multi-tiered air defence network—comprising the Iron Dome, David’s Sling and the Arrow system, now reinforced by the American-supplied THAAD battery—was considered near-impenetrable. Yet it has struggled to intercept a moderate number of Iranian missiles, many of which are decades old. This was against newer missiles that have the capability to manoeuvre in their terminal phase, these systems proved to be even less effective. The cost imbalance is stark: each Israeli interceptor missile can cost up to $3 million, while the munitions they destroy may be produced for a fraction of the cost. Israel’s attempt to strike at Iranian missile launchers has yielded limited results. Iran still retains the ability to strike at will. Although ballistic missiles devoid of nuclear warheads are of limited military use, nevertheless in a nation as small as Israel, they can cause significant economic and psychological damage.

Yet Iran, too, has been caught exposed. Its defences, largely a patchwork of ageing Russian systems and a smattering of locally produced platforms like the Bavar-373, proved startlingly ineffectual in the opening phases. Iranian air defence, it seems, has long been subordinated to the needs of ground forces—specifically the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), whose political loyalty to the clerical regime has often counted more than military necessity.

The cost imbalance is stark: each Israeli interceptor missile can cost up to $3 million, while the munitions they destroy may be produced for fraction of the cost

Unlike its neighbour Türkiye where investment focussed on producing state of the art and indigenous weapon systems, and their subcomponents, Iran squandered hundreds of billions on building a network of proxies, across the Middle East and beyond. That the IRGC, long the spearhead of Iranian regional influence, has seen its credibility eroded. Its network of proxies in Syria, Iraq and Lebanon—once thought to be a deterrent against Israeli action—has proven to be a liability rather than an asset. These groups, far from being an effective arm of Iranian resistance and revolution, have often operated with the tacit approval of the United States, securing US interests rather than exclusively Iran’s. They helped the US stabilise post-invasion Iraq, mobilized the Shia Hazara minority in Afghanistan against the Taliban and countered Sunni jihadist groups in Syria, all issues where the Iranians felt that their interests aligned with the US.

But it was simply folly. The US is a gluttonous power, it does not share, in its haste to prove its utility to the US it’s neglected to consider the full ramifications of its actions. Rather than buttressing the Assad regime if they had embraced the opposition in a similar manner to Iran’s relationship with Hamas and other Sunni political and jihadist movements, it would of gained significant influence and security from a new and friendly regime in Damascus. If Iran had instead of collaborating with the US in Iraq made the US occupation a more costly affair for the US both Syrian and Iraqi airspace would not have been safe spaces from which Israel could dismantle Iranian air defences.

For the US when their strategic utility waned, they were quietly neutralised—leaving Iran’s deterrence posture dangerously hollow.

More broadly, both Israel and Iran appear to have fallen victim to the same delusion: that they are indispensable to the United States in the Middle East. Israel assumed that its role as Western proxy would compel Washington to shield it from the consequences of escalation. Iran, for its part, believed that its tactical cooperation with the United States—in Iraq, Afghanistan, and even Syria—had earned it a degree of protection from Israeli reprisals. Both have misread the mood in Washington, where patience has worn thin and the appetite for protracted wars and entanglements in the middle east has given way to more important theatres’ of operation, the strategic focus has shifted elsewhere the US needs a quiet Middle East.

both Israel and Iran appear to have fallen victim to the same delusion: that they are indispensable to the United States in the Middle East

Although publicly belligerent, privately they admit that the real long-term threat to both of them—and to American interests in the region—lies not in each other, but in the potential emergence of a transnational Sunni Islamist caliphate. It is this spectre that has, paradoxically, made temporary and often tacit cooperation between Iran, Israel and America possible in the past.

Wars, like diplomacy, are about the management of illusions. Israel and Iran have both nurtured fictions about their strategic indispensability—and are now confronting the costs of believing them.

For Israel the lesson is severe it has proven to be indefensible even from a enemy located a thousand kilometres away, if war was to come to its border, its ability to resist will be measured in days rather than weeks, its population would be at the mercy of its enemies with little or no space to hide. To add insult to injury when US intervention did occur its came to impose an agreement and ceasefire on the Israelis, and gave the Iranians a face saving means to conclude the agreement already brokered. With the Fordow and Natanz facilities supposedly destroyed by the US bombing, Israel’s actual war aim which is to dismantle the Iranian regime is exposed and is forced to conclude without success.

Although the Israelis insist otherwise, it was not lost on the US, the EU and other sensible parties to the conflict that Iran’s stockpiles of highly enriched Uranium have always been a negotiating strategy rather than a serious attempt to build a weapon. Enriching to 60% is neither useful nor ornament, neither suitable for nuclear power or weapons without further processing or dilution. It simply constituted a bargaining chip that may elicit concessions when negotiations begin.

Israel’s intervention at the eleventh hour, when negotiations between all parties were to be concluded and a deal signed, is judged as an unwarranted escalation, like its sparring partner Iran, Israel is now considered part of the problem rather than its solution.

Iran once drunk on its success in creating its so-called Shia crescent, its strategic gains have been reversed in hours and days, lands once considered part of its security sphere are now safe havens from which its enemies launch attacks. Once considered the bogey man of the Middle East it seems Iran is surprisingly impotent in the face of determined opposition.