The population of the Middle East has been on an upward trajectory for over 100 years and this will remain the case for the next century. Despite the discovery and development of energy in the region the region’s economies have not kept pace with population growth and all of the nations that constitute the Middle East suffer from deep structural issues with their economies.’

The first Arab Human Development Report (AHDR) in 2002 characterised the Arab world as “richer than it is developed.”[1] That description highlighted the contradiction between the region’s material wealth and its real levels of human development, which pointed to a backlog of policy failures often overlooked by conventional economic analyses. Yet the fabled oil wealth of the Arab countries is itself misleading in that it masks the structural weaknesses of many of the region’s nations. Across the region there is a consistent pattern of massive policy failure on very basic matters such as food security, education, development and employment. The World Bank reported in 2011 that over 210 million people live below the $5 dollars-a-day international poverty line.[2]

The story of Arab economies since the 1970s is largely the story of oil. Producer countries gained most, amassing untold wealth, but non-oil Arab countries also benefitted substantially from oil-related services, worker remittances, intra-regional investment flows, regional tourism receipts, and aid. Arab oil revenues fuelled extraordinary wealth and rapid infrastructural and other areas of development in the 12 oil producing states of the region, accounting for almost 90% of their annual public budgets. These revenues also powered associated industries, jobs, income and remittances for the citizens of other Arab states. Oil income is thus a major driver in the economic security of the region. But the rulers in the region opted to put much of their energy windfall into foreign investments, external reserves and oil stabilisation funds, foreign military equipment and to repay debts. Very little of this money has been used to construct industry which would have created many jobs, stimulated the economy and brought in taxation for central government.

Oil-led growth has created weak structural foundations in Arab economies. Many Arab countries turned into import oriented and service based economies. The types of services found in Arab countries fell at the low end of the value added chain, contributing little to local knowledge development, and locked countries into inferior positions in global markets. This trend, has been at the expense of Arab agriculture, manufacturing and industrial production. Not surprisingly, most Arab countries have experienced significant deindustrialisation over the last four decades. In fact, the Arab countries were less industrialised in 2007 than in 1970, almost four decades ago. This includes nations with a relatively diversified economic base in the 1960s, such as Algeria, Egypt, Iraq and Syria – although Jordan, Oman, Tunisia, and UAE made noticeable progress in industrial development. Nonetheless, in general, the contribution of manufacturing to GDP is anaemic, even in Arab countries that have witnessed rapid industrial growth.

A number of nations in the region have a heavy reliance on oil exports; this has created a dependency on the oil process and has kept such economies narrowly focused. The energy infrastructure in the region was constructed by foreign companies and today is dominated by foreign companies. Very little technology or knowledge transfer has taken place which could have reduced unemployment significantly. The regional nations have also embarked on major domestic investments in real estate, construction, oil refining, transport and communication and social services. Such huge energy wealth remains in the hands of monarchs, families and business elites with the vast bulk of the population languishing in poverty. In Saudi Arabia the oil wealth remains within the royal family who subsidise the lifestyles of their expanding family or the wealth is spent bailing out Western institutions.

The non-oil economies in the region such as Sudan, Tunisia, Egypt, Algeria, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, whilst rich in Agriculture and minerals rely upon oil-related services, worker remittances, intra-regional investment flows, regional tourism receipts and aid. This has led to a reliance on food imports that has resulted in more and more of government budgets being spent on food due to the rise in international food prices. The subsequent food riots have led to governments in the region resorting to food and fuel subsidies which have not dealt with any of the underlying problems of food security.

Food security and agriculture in general remain problematic in the region. A third of the agricultural production in the region is exported abroad to earn foreign currency reserves, this is at a time when most of the region is in poverty and with some nations struggling with agricultural production due to the climate.

Unemployment is a major source of economic insecurity in most Arab countries. At the end of 2014 unemployment was at 11%, the highest in the world, with youth unemployment at 30%. This has been mainly caused by the large and unsustainable role public sector plays. The limited size, hobbled performance and weak job-generating capacity of the private sector have also not helped the wider economy.

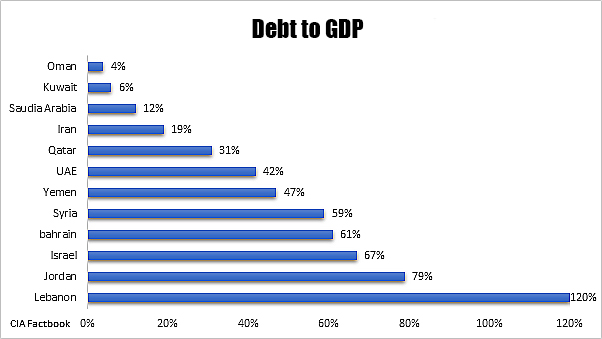

The inability of many of the region’s countries to develop sustainable sectors of the economy has resulted in 14% of regional export earnings going to debt servicing. In Lebanon, debt servicing accounts for 47% of the government’s budget. Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia spend more on debt servicing than they do on education; all spend twice as much on debt service than they do on health care. Sudan and Yemen are among the 41 countries identified as Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPCs).

Like much of the world wealth is unevenly distributed across the Middle East. Monarchies and dictators control most of the wealth and they ensure their support base benefit from this only. Wealth is usually used to maintain social cohesion and to keep the masses occupied with day-to-day fulfilment of basic needs rather than the corrupt rulers. Nearly 50% of the region’s wealth is held by just 20% of the population.[3]

With a growing population and lack of food security, many rulers in the region maintained their grip through subsidies. This ensured the cost of food, fuel, electricity and many other basic necessities being subsidised by the state. In the Middle East, generalised price subsidies have for many years been part of society. But generalised price subsidies have not been well targeted or cost-effective as a social protection tool. Though subsidies may reach the poor and vulnerable to some extent, they benefited mostly the better off, who consume more of subsidised goods, particularly energy products: for example, in Egypt in 2008, the poorest 40% percent of the population received only 3% of gasoline subsidies. Middle East and North African nations are now struggling to maintain their subsidy programmes. Total pre-tax energy subsidies in 2011 cost $237 billion – equivalent to 48% of world subsidies, 8.6% of regional GDP, or 22% of government revenues. They amounted to $204 billion (8.4% of GDP) in oil exporters and $33 billion in oil importers (6.3% of GDP). Food subsidies are also common in the region, though less costly. In 2011, they amounted to 0.7 percent of GDP for the region. With a growing population in the region and with the advent of Shale energy to keep energy prices low, the energy jackpot will in all likelihood not be able to fund future subsidies. But with poverty still high in the region, any removal of subsidies will lead to price increases which will lead to instability – the very thing the subsidies were created to stop.

The lack of a sustainable driving engine for the region’s economies has resulted in unemployment and the lack of direction for the economies of the region has led to weak job-generating capacity. All of this has been plugged by unsustainable subsidies. According to Sundeep Waslekar, a researcher from the Strategic Foresight Group: “Autocratic, oil-rich rulers have been able to control their people by controlling nature and have kept the lid on political turmoil at home by heavily subsidising “virtual” or “embedded” water in the form of staple grains imported from the US and elsewhere.”[4] Going forward, there is few places in the world that will be subject to as much pressure from growing numbers of people as the Arab world. This rising population will need to be watered, housed; they will need new and modern transportation systems and labour markets. Competition for jobs, especially government jobs, and housing and the poor quality and inadequate provision of public services are prime causes of the deep dissatisfaction with the status quo that marks so many of these societies. The stress these demographic pressures exert—and regional governments’ ability to mitigate them—will play a major role in determining the future trajectory of the region.

[1] http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/rbas_ahdr2002_en.pdf, pg 26

[2] http://www.worldbank.org/en/region/mena

[3] Inequality and Arab Spring Revolutions in North Africa and the Middle East, African Development Institute, Vol 3, issue 7, 2012, pg 7, http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/AEB%20VOL%203%20Issue%207%20juillet%202012%20ENG_AEB%20VOL%203%20Issue%207%20juillet%202012%20ENG%202.pdf

[4] What does the Arab world do when its water runs out? Guardian, February 2011, retrieve July 13 2015, http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/feb/20/arab-nations-water-running-out