With the electoral victory of Ebrahim Raisi, the ultra conservative head of Iran’s judiciary was always a foregone conclusion. There was nothing left for his rivals to do but congratulate him on his victory. With the reformist bloc hobbled at the first hurdle, it was not surprising that Raisi garnered 17.8 million votes, a colossal 14.5 million more than his nearest rival, he was in effect the only viable candidate.[1] But whether the president is a reformist or conservative, the clerical regime faces its biggest test since seizing power over four decades ago.

Ebrahim Raisi’s victory secures for the conservative establishment, both elected and unelected nodes of power, and for the first time since 2007 a conservative consensus which exists unopposed in government. Although Ebrahim Raisi may now command almost unilateral power and without a dramatic fall from grace, will most likely secure the position of supreme leader, the challenges that face both the clerical regime specifically and Iran in general are both deep and intractable.

It is only with a healthy dose of scepticism that a conservative victory in an election which saw the majority of reformist candidates including former parliamentary speaker Ali Larijani and Vice President Eshaq Jahangiri disqualified by the Guardian Council be taken as a endorsement of the clerical establishment which has ruled Iran since the revolution of 1979.[2] Rather disenchantment with the regime in particular and clerics in general has become a defining feature of the Iranian political landscape.

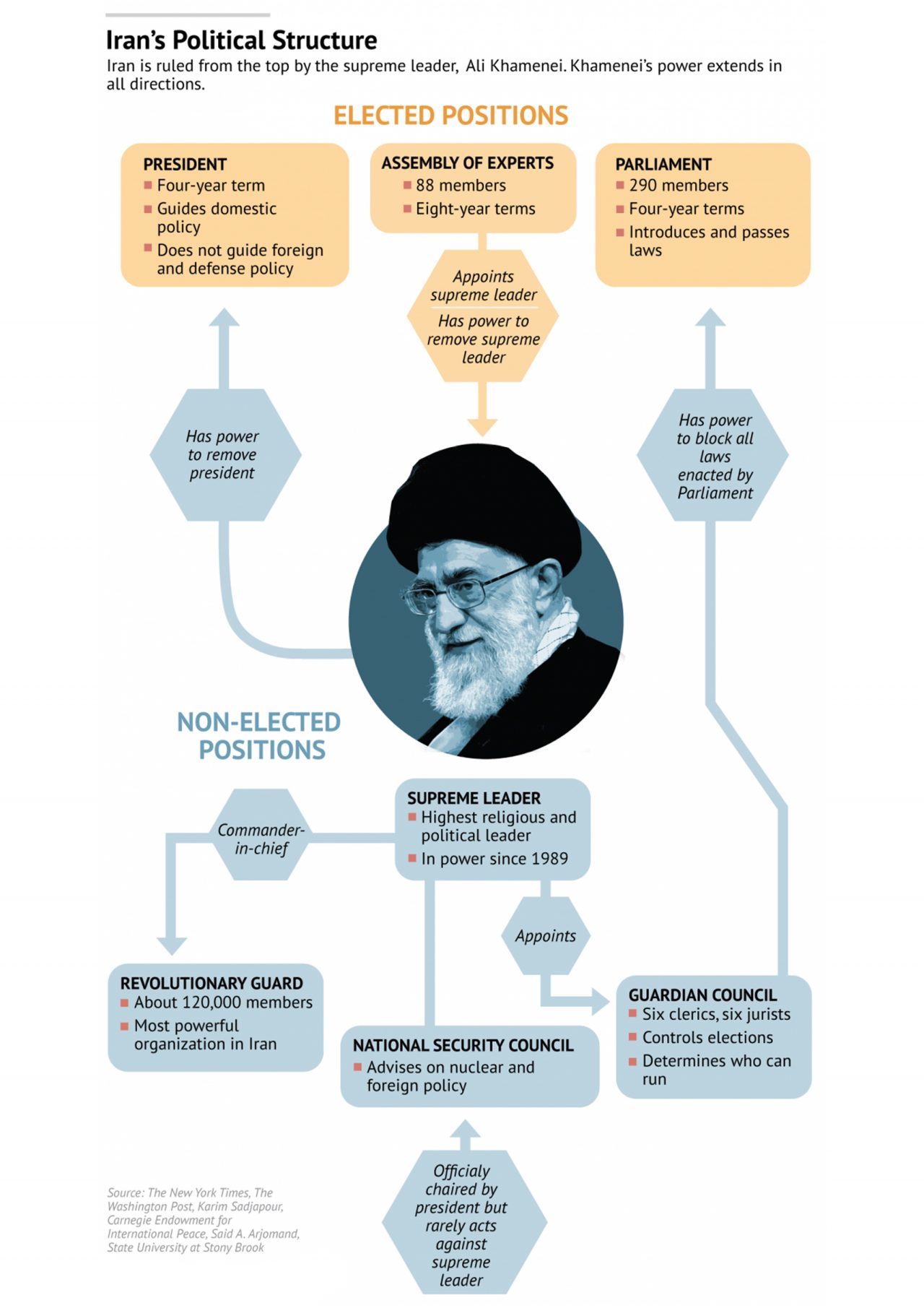

It is only the phalanx of the guardian council, the political, economic and military weight of the IRGC that keeps the reformist at bay. Far from the ideals of the so-called Islamic revolution, the clerical regime has become a coterie of vested interests, with patron clerics vying for state largesse which is then apportioned to their various clients and followers. The transformation of the clerical regime into a vast and distributed client patron network, dissolves any vestiges of meritocratic appointment and rational allocation of state revenue. The façade of a rigged election only papers over the cracks of a clerical establishment that enjoys diminishing legitimacy at best and derision from those that fail to benefit from their ill-gotten gains. Reigning in the clerics and divesting the various Bunyods (Cleric run foundations) of their ill-gotten gains is a task that the new president will have to complete to restore even a fraction of the legitimacy formerly enjoyed by the clerics.

Although the economy of Iran is more diverse than most of its Arab neighbours, it is still reliant on oil for the majority of its export earnings and state revenue. The fall in oil prices significantly affected government revenue, and it was only the timely intervention of US president Barack Obama and the JCPOA nuclear agreement in 2015 that partially mitigated the nearly 50% fall in oil revenues . Iran’s dependence on oil and gas exports as the primary source of state revenue, leave the state and population open to the vagaries of the international oil and gas markets. Weaning the Iranian economy away from its dependence on oil, to a more mixed economy similar to its erstwhile neighbour Turkey is a priority, for the new president, especially when one considers the global shift away from fossil fuels.

Far from the ideals of the so-called Islamic revolution, the clerical regime has become a coterie of vested interests, with patron clerics vying for state largesse which is then apportioned to their various clients and followers

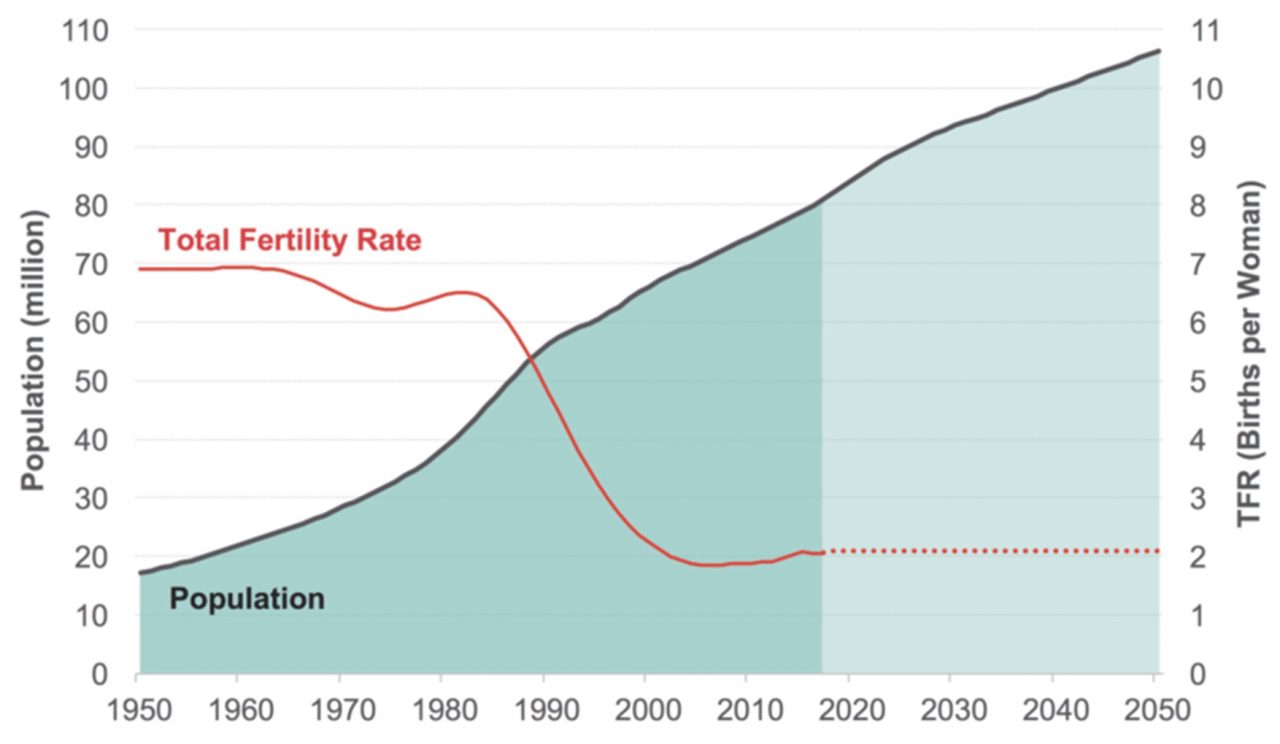

Even without the collapse of oil revenues, the Iranian economy has failed to keep up with its rapid population growth. Iran’s population has grown from 16.4 million in 1950 to 39.7 million at the time of the Shah’s fall in 1979. Today Iran’s population is 82 million. With over 850,000 young Iranians entering the job market every year and youth unemployment optimistically declared as 27%, but more likely double than this, Iran’s economy has failed to generate adequate employment for its aspiring youth.[3]

Unlike many of its Middle Eastern neighbours’ Iran does in fact possess a technically proficient and industrious work force, but ossified decision making, nepotism and suffocating state-controlled enterprises have divested Iran’s economy of much of the vitality and dynamism that is required to foster adequate growth. Rolling back state control and opening the economy for private enterprise and entrepreneurships will in the long term diversify and grow the economy, despite short term economic pain.

Economic mismanagement and the effect of US and EU sanctions has resulted in Iran being in the unenviable position of possessing an inflation rate double that of its GDP growth, in effect impoverishing its population. Household income has a witnessed a sharp decline in real terms, tackling inflation should be the primary objective of the new president.[4]

Internationally Iran has expended huge resources with very little gain. The recruitment and equipping of tens of thousands of Shi’ah militia in Syria and Iraq paradoxically has not provided the clerical regime with the regional power status it covets. The future of Syria and Iraq continues to be decided in Washington, Moscow and Brussels rather than Tehran. The existence of the militias, apart from sowing the seeds of mistrust across the Sunni world, are an expense that the regime can ill afford. Declining living standards of the common man prompt them to call into question the regimes preoccupation with foreign misadventures rather than domestic economic reform.[5] If Iran is to reintegrate into the Middle East the demobilization and reintegration of these militia without the inevitable slide into criminality and organized crime will be a key challenge.

Despite the bellicosity of the clerical regime the impotence of the Iranian clerical regime is brought into sharp focus by its inability to respond to the assignation of Qassim Solomani by the US and the killing of key personnel involved in its nuclear program by Israeli operatives who shockingly operating inside Iran, and with the de facto return of the Taliban to governance in Afghanistan another front opens up on an already stretched regime.

[1] Conservative Ebrahim Raisi tops Iran’s presidential candidates | Elections News | Al Jazeera

[2] Hardliner Ebrahim Raisi hailed as Iran’s new president | Iran | The Guardian

[3] The Crisis in Iran: What Now? | Center for Strategic and International Studies (csis.org)

[4] Mismanagement Leaves Iran’s Economy Vulnerable | The Washington Institute

[5] Iran’s Allies Feel the Pain of American Sanctions – The New York Times (nytimes.com)