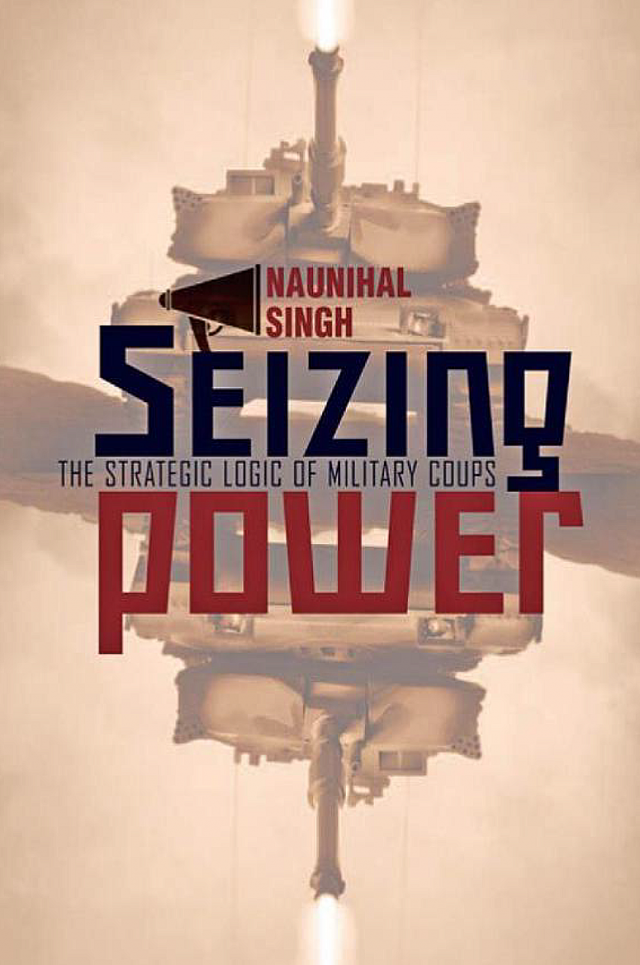

Seizing Power: The Strategic Logic of Military Coups

By Naunihal Singh

2016

In 1991, in a last-ditch effort to save the Soviet Union from dissolution, a coalition of the top military and civilian leaders in the country tried to seize power from Mikhail Gorbachev. Except for the premier himself, the conspirators included every major official in the state apparatus such as the defence minister, interior minister, KGB chief, the prime minister, the secretary of the central committee and the chief of the President’s staff. Despite the overwhelming force the coup makers had at their disposal — the coup attempt failed.

Almost ten years earlier, on New Year’s Eve 1981, a young retired flight lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings led a very different military coup in Ghana. In this attempt Rawlings and just a handful of men managed to take control of a military of 9,000 and a country of 11 million. Unlike the Soviet conspirators who commanded virtually the entire security apparatus and represented the entire state, Rawlings attacked with only ten men carrying small arms and broader alliances with mainly disgruntled enlisted men and student radicals. Yet, despite all these seeming obstacles, Rawling’s coup prevailed.

Why did the 1991 Soviet Union coup attempt fail and the 1981 Ghana coup attempt succeed? Why do 51% of all coups succeed and 49% fail? This is the question Professor Naunihal Singh of international security studies at the air war college, Alabama, aims to answer. The answer to this anomaly has bothered me for some time now. Even after reading numerous books on the subject and watching multiple documentaries and films, I for long felt I didn’t have a comprehensive framework that answered this question.

Singh’s conclusions are based on an empirical evaluation of all 471 coup attempts from 1950 to 2006, drawing on various interviews with retired military personnel and over 300 hours of interviews specifically with coup participants from Ghana. Whilst most research on coups has focused on successful coups and not those that failed, Singh doesn’t follow the mainstream view that looks at coups as referendums on the ruler or as battles between two parties with the strongest winning.

Singh develops his own framework, drawing on game theory where individual choices are based on the expectations and beliefs of what others will do. These expectations can be created by using the available means of communication to shape expectations. Singh argues that the pivotal factor in a coup’s success or failure is not its intrinsic popularity but rather its leaders’ ability to persuade others that the coup is broadly supported and likely to succeed. Consequently, seizing control of the national TV broadcaster or the radio facilities, can be important to project the impression of the coup’s solidified control. Singh examines seven coup attempts that took place in Ghana between 1967 and 1981 in much detail by interviewing the officers that led and participated in these coups.

For Singh, a coup will succeed or fail based upon the plotters creating the expectations that it has already succeeded and the rest of the military should get behind it. The biggest challenge to achieving this is organisational; the rank level the challengers occupy within the armed forces. Coup makers from the top, middle and bottom of the military possess very different resources with which to create expectations, leading to three distinct trajectories with different likelihoods of success.

Singh’s theory is easy to grasp and can be applied upon other coups not covered in his book. The theory explains the likely dynamics and outcomes of military coups, which provides an explanation of why some coups fail despite the coup makers’ having tactical might and why others fail despite the unpopularity of the incumbent government. Rank matters in coup making and explains why coups launched by military actors nearer the top of the military hierarchy have a better (though never a guaranteed) chance of success.

There are also a number surprising conclusions from Singh, which I had not considered previously. Such as coups being largely an intra-military affair, they are not influenced by external factors. He also alludes to the fact that a foreign sponsor of a coup is not guaranteed success, the coup plotters still have to create expectations and carry out the coup. Singh also concludes that whilst military officers are willing to fight to the last man to defend their country against an external invasion, they do not want to engage in fratricidal bloodshed that might damage the military and the country and perhaps spiral into civil war. Military officers, Singh found through interviews, cast their support to the side, they believed everyone else would back as well as the side that would win rather than the one they might have wanted to win.

Modern media communication platforms such as social media, Singh believes, do not currently possess the credibility to build expectations for a coup. As Singh asserts officers sending a tweet or Facebook post that they are undertaking a coup is not seen by the masses the way coup plotters would take over the national broadcaster and declaring their coup in the morning or evening news.

If there is one reason to fork out the price of this book, it’s for Singh’s analysis and conclusions on why Soviet Union coup failed in 1991. Using his framework, he provides a comprehensive answer that despite the conspirators’ confidence they failed to use the resources at their disposal. This left room for the Russian Chairman, Boris Yeltsin, and his allies in the media to hijack the content of public broadcasts and create self-fulfilling expectations that the junta was not in control. These repeated public assertions that the junta was not in control became a self-fulfilling reality, within the military itself, that led to the coup’s failure.