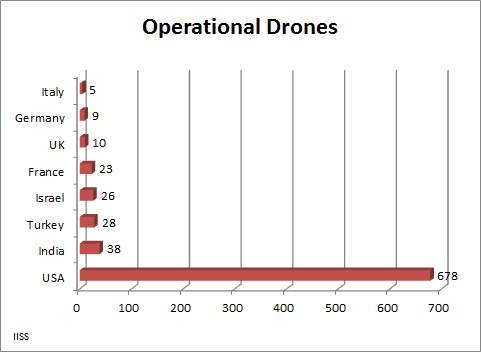

America’s war in Afghanistan and Pakistan has seen the widespread use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV), commonly known as drones. Whilst much debate continues on the moral aspect of their use, this military platform is now a critical aspect of America’s global military footprint. UAV usage is rapidly increasing throughout the world and has doubled in just the last 5 years. This trend is set to continue, but all drones are not created equal. There is a huge variation in physical structure, capabilities and the systems used on these platforms. UAVs are a subset of the broader category of unmanned vehicles that operate on land, on and below the ocean, and in space. UAVs are currently the most prominent and advanced in military utility, but other subsets such as unmanned underwater vehicles are also being developed. However, UAVs suffer from inherent shortcomings and this will keep the platform a complementary system, rather than a replacement to manned fighter aircraft.

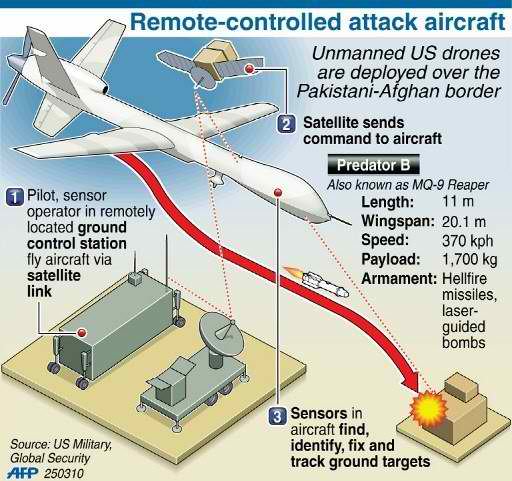

UAV operations are all about data. Everything its sensors see must be received by the controller, and every command the controller gives must get to the drone. Getting this data across space requires infrastructure. In its simplest form, this can be an advanced remote control, but this means you have a very limited operational range. In more advanced versions, portable ground stations can be set up with powerful transmitters and antennas that extend this reach. In the most advanced versions, complex data systems and space-based satellites can be networked and used to project data over vast distances. For all of this to take place these drones require logistical networks and access to airfields just like all aircraft. For all practical purposes any nation wanting to deploy drones will need forward bases and plenty of IT infrastructure to operate them. This is a big vulnerability as such facilities would need to be in close proximity to the battlefield making them susceptible to a strike, which would end their use.

UAV operations are all about data. Everything its sensors see must be received by the controller, and every command the controller gives must get to the drone. Getting this data across space requires infrastructure. In its simplest form, this can be an advanced remote control, but this means you have a very limited operational range. In more advanced versions, portable ground stations can be set up with powerful transmitters and antennas that extend this reach. In the most advanced versions, complex data systems and space-based satellites can be networked and used to project data over vast distances. For all of this to take place these drones require logistical networks and access to airfields just like all aircraft. For all practical purposes any nation wanting to deploy drones will need forward bases and plenty of IT infrastructure to operate them. This is a big vulnerability as such facilities would need to be in close proximity to the battlefield making them susceptible to a strike, which would end their use.Most UAVs are slow, easy to see and virtually defenseless. Lacking the agility of fighter jets, drones cannot operate well in hostile airspace. Gen. Mike Hostage, chief of the US air service’s Air Combat Command, confirmed: “the drones that have proved so useful at hunting al Qaeda are useless in nearly every other battlefield scenario. Predators and Reapers are useless in a contested environment today. I couldn’t put [a Predator or Reaper] into the Strait of Hormuz without having to put airplanes there to protect it.” [1] Despite their widespread use in Afghanistan and Pakistan, US drones have not faced any challenge in the airspace above both countries as their leaders have been in complete cahoots with the US and as a result US drones faced no opposition. In a contested airspace, drones as a weapon system are near useless. Gen. Mike Hostage confirmed: “MQ-1s and MQ-9s have limited capability against even basic air defences. We’re not talking deep over mainland China; we’re talking any contested airspace. Pick the smallest, weakest country with the most minimal air force — [it] can deal with a Predator.”[2] The development of stealth drones is an attempt to overcome such limitations. [3]

In an air war, an advanced aerial threat environment increases the likelihood of within-visual-range air combat, often referred to as “dog-fighting.” Dog-fighting presents the most dynamic aerial environment conceivable. Survival requires both proactive and instantly reactive three-dimensional aircraft manoeuvring. Success requires critically outthinking an adversary while making split-second decisions, executing demanding manoeuvres under crushing g-loads, and firing weapons at an enemy. At present, these are critical tasks that only pilots physically engaged in the battle can do. Distantly controlled unmanned aircraft lack these capabilities. If ever caught in a dog-fight, they transition from lethal airborne assets to defenceless targets.

The biggest problem currently with drones is the GPS navigation system. GPS signals are weak due to the distance they travel and can be easily out punched (overridden) by stronger local signals from television towers and devices such as laptops or mobile satellite services. In a report on GPS Spoofing the C.S. monitor highlighted: “The GPS navigation is the weakest point, by putting noise (jamming) on the communications, you force the bird into autopilot. This is where the bird loses its brain.”[4] A more pernicious attack involves feeding the GPS receiver fake signals so that it believes it is located somewhere in space and time that it is not. Former US Navy electronic warfare specialist Robert Densmore highlighted: “Even modern combat-grade GPS [is] very susceptible to manipulation, it is certainly possible to recalibrate the GPS on a drone so that it flies on a different course. I wouldn’t say it’s easy, but the technology is there.” This was the method Iran reportedly utilised to ‘trick’ a US drone into landing in the country in 2011.[5] The US military continues in seeking alternatives to the GPS system of satellites. But fundamentally GPS signals travelling over long distances can be easily overwhelmed with a stronger local signal.

Whilst much of the debate regarding drones has centred on their moral use, their use in Pakistan, Afghanistan, Somalia and Yemen has only been possible due to the governments in these countries handing over their airspace to the US. As a platform, drones suffer from numerous inherent shortcomings which make it extremely unlikely they will replace the manned flight. The US is planning to expand its use of drones to other theatres of war allowing for the orchestration of an entire battle group managed by a handful of people[6], but all of this is predicated upon political support from the rulers of such countries.

[2] Ibid