By Adnan Khan

“Don’t forget, China’s current success is built on 300 million people taking advantage of 1 billion cheap labourers. And the unfair judicial system and the unfair distribution of wealth are making the challenges even greater.”[1] Zhou Xiaozheng, Institute of Law and Sociology at Renmin University of China

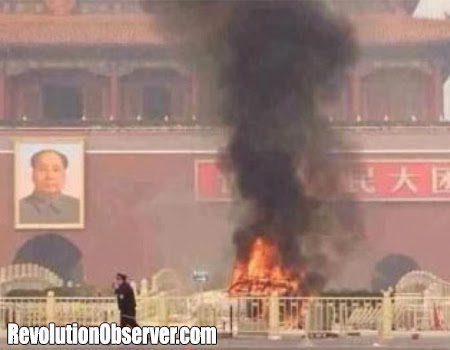

On October 28 2013, an automobile plowed into a group of pedestrians and burst into flames on the avenue next to Tiananmen Square, the massive public square in Beijing which is the symbolic heart of the Chinese capital. Chinese police considered the incident an act of terrorism, a suicide attack carried out by three Uyghur Muslims.[2] China’s largest province – Xinjiang, has long troubled Beijing; the restive region in the northwestern part of the country has not been part of the country’s three decades economic miracle. Despite the rhetoric, when placing the attack in perspective, grievances over systematic injustice, remain the greatest threat to the Chinese government and the mounting discontent and grievances are primarily among the ethnic Han majority.

China faces a demographic problem of colossal proportions. With the world’s largest population of 1.3 billion, feeding, housing, protecting, educating and maintaining such a vast population is an enormous challenge. This problem is also not new. For centuries, China has attempted to hold together a vast multi-cultural and multi-ethnic nation despite periods of political centralization and fragmentation. China has a long history of societal upheaval of gigantic proportions. Regularly through its 4000-year history everything came crashing down as each attempt at development cracked from its seams. The death of Mao Zedong in 1976 led to the emergence of the reformist movement and chief architect of China’s current economic development – Deng Xiaoping. Under his leadership it was concluded that China’s population and in particular its growth, could become the nation’s Achilles heel. If population growth was not matched with economic growth and employment then the resulting mass unemployment would cause mass poverty, civil unrest and a revolt against the rule of the Communist Party.

Whilst the Communist party’s totalitarianism is what receives most of the media headlines, the communist party’s main strategy of maintaining social cohesion has been through the economy. China attempted to deal with social cohesion through ensuring full employment. China is an export driven economy, built to produce goods which are exported around the world. As long as China remains the world’s largest and cheapest exporter, mass employment is the outcome for Chinese citizens. China manipulates its currency, by keeping its exchange rate artificially low, ensuring its exports are the cheapest globally.[3] Full employment achieves territorial cohesion for the Communist government.

China’s economic miracle is now faltering and this is bringing the underlying discontent to the surface. China’s rapid economic development has been anything but equal. The Special Economic Zone’s (SEZ) were all constructed on China’s Eastern coast and everything that came of the production line was placed on ships as cargo and exported to the world. The coastal region as a result was interlinked with the global economy; it has seen most of China’s rapid development and enriched a new breed of elites, all at the expense of the rest of China. A large chunk of China today remains largely agrarian, has little infrastructure and lives in poverty. According to the Boston Consulting Group 2008 worldwide study of household wealth, 70% of China’s wealth is controlled by only 0.2% of its population.[4] Such wealth misdistribution is compounded by physical mistreatment, imprisonment, lax labour laws, pitiful pay and the fact that the Chinese government is seen not to have addressed the economic needs of the vast bulk of the population. In 2005 China handled 87,000 cases of social unrest; including public disturbances, demonstrations and civil strife. In 2010, China was rocked by 180,000 protests, riots and other mass incidents, more than four times the tally from a decade earlier.[5] Domestically China is a very unstable society.

The Chinese leadership has not addressed this fracture in any clear way. All the trends point to the continued use of nationalism. The Chinese leadership has historically attempted to deal with social cohesion through promoting nationalism. Chinese nationalism has in the modern era been about China’s 4000 years of glorious history and its modern humiliation by Japan and the west. Today, Chinese nationalism is characterized by the relationship between the population’s feelings of pride, disappointment and hope for China’s future. This policy has in reality been a tool by the Communist Party for social management and securing party control. Nationalism has been a volatile strategy for social cohesion by those who have utilised it. For unifying a populace, nationalism has caused more violence in almost all cases.

China’s rapid economic growth has masked its underlying weaknesses. Its economic model of exports and low wages is now struggling and this is bringing the underlying discontent to the surface. China attempted to maintain social cohesion by creating economic prosperity; yet it is not economics or commerce that create cohesion but values that bind societies together. However, even the use of Chinese nationalism as a binding philosophy did not address this issue. China today is at the same critical juncture it has been at on a number of occasions in its 4000 year history. China’s internal deficiencies, masked by a period of relative prosperity and stability, are now becoming more apparent: and if we go by Chinese history, its implosions are always of gigantic proportions.

[4]Wealth Markets in China, The beginning of the race for china’s rich, Boston Consulting group, October 2008, pg 8, http://www.bcg.com/images/file7715.pdf