By Adnan Khan

The month of April has seen a flurry of reports on energy exploration in the Eastern Mediterranean. Ever since the 23 March apology by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu over the Turkish flotilla deaths, a number of energy projects between Turkey and Israel have come to light. Turkey, Israel, Cyprus and Lebanon have all been looking to develop the sea’s offshore energy reserves. Overall, these are very ambitious projects as they will include underwater pipelines and floating liquefied natural gas terminals. As well as these challenges, much of the reserves have not actually been proven; which raises further questions about the technological and logistical requirements. What is for certain is the region’s desperate need for energy.

Transforming the eastern Mediterranean into a hub for energy exports has long been an aim by the nations that share borders with the waters. Offshore exploration in the waters of the Eastern Mediterranean region started in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. These wells targeted structural culminations on the shallow shelf of Israel and northern Sinai, but all were found to be dry. Exploration activity in the offshore Eastern Mediterranean re-emerged in 2000, when five natural gas fields were discovered at a shallow depth west of the coastal town of Ashqelon and the Gaza Strip. These discoveries speeded up exploration efforts and promoted the acquisition of geophysical data throughout the entire Eastern Mediterranean area, particularly in the Levant basin. In 2009, the US Company Noble Energy announced the discovery of the Tamar field in offshore Israel. After this first major discovery, Noble Energy announced two other major findings in the Levant Basin: the Leviathan field in offshore Israel and the Aphrodite field in offshore Cyprus.

Turkey has very limited energy resources, but because of its strategic location between Europe and Asia and between oil consumers and oil producers, it is crossed by several major oil and gas pipelines. Turkey’s geographical location makes it a natural trans-shipment route between the major oil producing areas in the Middle East, Central Asia, and the Caucasus on the one hand, and consumer markets in Europe on the other. Europe’s attempts to circumvent Russian energy, regularly used as a political tool by the Russians, has made Turkey an important nation for Europe’s future energy security. The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline, considered one of longest oil pipelines in the world, delivers crude oil from the Caspian Sea basin to the port of Ceyhan on Turkey’s Mediterranean coast, from where it is distributed with oil tankers to the world’s markets. From a geopolitical perspective Turkey is critical to the world’s energy security.

Israel for long struggled to meet its domestic energy needs. While it still lacks oil reserves, discoveries in the 2009 of natural gas has had the immediate effect of covering Israel’s rising domestic needs, and will allow it to also export its surplus natural gas. The Israeli strategy has rested on integrating its energy with the region, especially Turkey. Since 2009 Israel has attempted to use its natural gas reserves as a tool to normalise its existence through locking countries such as Jordan, Cyprus, Syria and Egypt as well as Turkey into natural gas deals. However a number of proposed pipelines, deep water pipelines and LNG terminals, are still to materialise due to having to traverse ambiguous Lebanese and Syrian waters. With the northern Levant fragmenting under the pressures of the war in Syria and no credible government to enforce any agreement, these maritime boundaries will remain undefined for the foreseeable future.

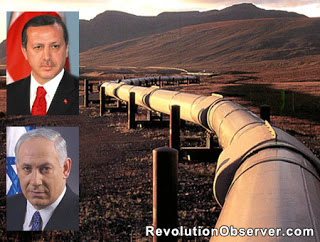

For Israel, exporting gas via Turkey is the jewel in the crown, as Turkey has the infrastructure, ports, markets, and insurance readily set up. As relations soured between the two countries, Israel constantly reiterated that such a break in relations is delaying the progress in Turkish-Israeli energy relations. However, whilst in public the Erdogan-led government appeared to have cut relations with Israel, energy ties have continued and progressed. On April 9 2013 Michael Lotem, the Israeli foreign ministry’s special energy envoy, was present at an oil and gas conference in Ankara. In one short speech and a few panel comments he made sure his message was clear: Israel’s door is open to such a deal.[1] The deal in question is the construction of a pipeline that transports Levant Basin gas under the Mediterranean Sea to southern Turkey to market its gas to Western Europe. Turkish international relations expert Soli Ozel of Istanbul’s Kadir Has University said regarding the potential deal: “The issue may become an important topic that the two can cooperate on. The Israelis have already made a suggestion to send some of their gas by pipelines to Turkey. And this fits well with Turkey’s grand desire to be the grill full of pipelines from north to south, from east to west, and therefore become on energy matters, if not a hub, certainly an indispensable transition place.”[2]

Whilst there are numerous technical and logistical issues surrounding the development of Eastern Mediterranean energy, Turkish-Israeli relations will be central to any progress. No sooner had Netanyahu apologised to Turkey, the energy deal was the first news item to hit the headlines, which indicates that talks have continued to take place on the issue. Both countries for domestic reasons needed to be seen holding their positions, and it was here the US stepped in. Alon Liel, a former Israeli ambassador to Turkey highlighted what really took place: “Obama and Kerry worked on it the last two months, and they made the difference. With the whole region in such turmoil, it was very difficult that the two allies of the US in the region were not cooperating.”[3]

For the prize of energy deals, the U.S. intervenes relentlessly, Israel forsakes its pride and apologizes, and Turkey forsakes the blood of the brave men murdered on the flotilla. The wealth and resources of the Muslim Ummah are once again offered at little price to satisfy the hungry Capitalist machinery, while the people to whom the wealth belongs are offered little information, let alone their approval sought.