By Malik Abu Luqman

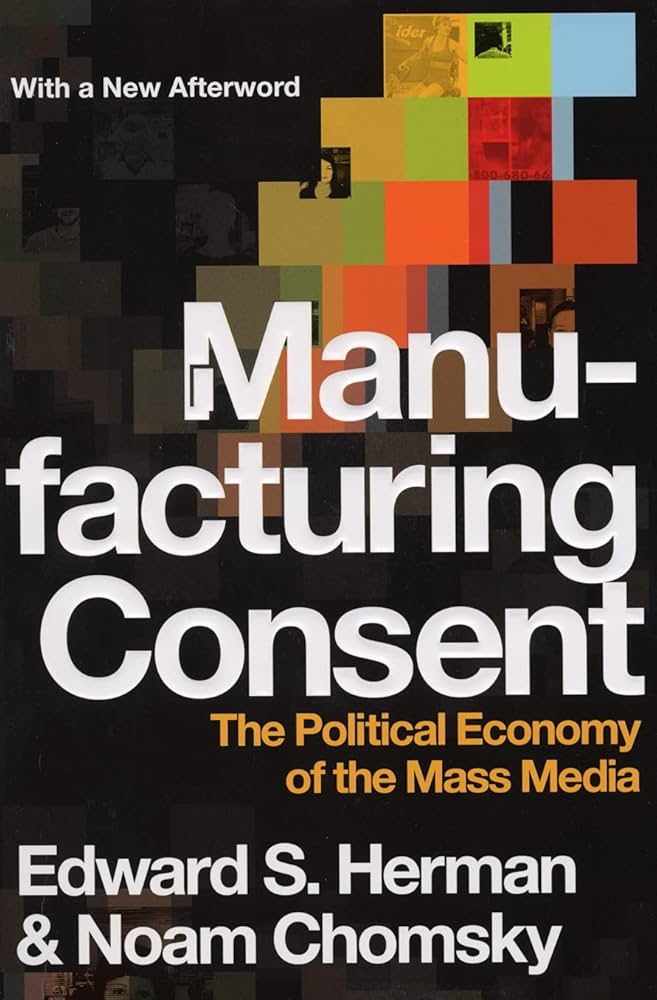

Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media

Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman

1988

Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman’s “Manufacturing Consent” provides a framework for understanding how mass media functions as a propaganda system serving elite interests. The book, written during the Cold War, systematically examines how American media coverage shifts based on whether events align with or challenge elite interests. Through this comparative analysis, the authors demonstrate that rather than fulfilling its stated mission of holding power accountable, the US media system operates as a propaganda model serving elite interests.

Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman’s “Manufacturing Consent” provides a framework for understanding how mass media functions as a propaganda system serving elite interests. The book, written during the Cold War, systematically examines how American media coverage shifts based on whether events align with or challenge elite interests. Through this comparative analysis, the authors demonstrate that rather than fulfilling its stated mission of holding power accountable, the US media system operates as a propaganda model serving elite interests.

The propaganda model identifies five key filters that shape media coverage: ownership concentration requiring massive capital investment, advertising dependence, reliance on official sources, flack (organised backlash), and anti-extremism (formerly anti-communism). These filters systematically bias coverage in favour of establishment perspectives while marginalising dissenting views.

The book demonstrates this bias through a comparative analysis of “worthy” versus “unworthy” victims. A striking case study contrasts coverage of the murder of Polish priest Jerzy Popieluszko (worthy victim from a Communist state) with four American churchwomen killed in US-allied El Salvador (unworthy victims). The quantitative analysis revealed Popieluszko received three times more articles (94 vs 31) and five times more column inches of coverage (1500 vs 300) – equivalent to comparing a nine-story building to a two-story house. Qualitatively, his case featured detailed violence descriptions, prominent placement, sustained coverage, and aggressive investigation of government involvement.

This framework remains relevant today, as shown by The Intercept’s analysis of Gaza coverage. Deaths of Zionists receive 16 times more mentions than Palestinian deaths, while emotive terms like “slaughter” (60:1), “horrific” (60:1), and “massacre” (120:4) are overwhelmingly reserved for Zionist victims. Even headline framing subtly manufactures consent – compare “Buildings Damaged in War” versus “Forces Responsible for Destruction” when describing similar events in different contexts.

The media’s role extends beyond simple misinformation to sophisticated manipulation of coverage intensity and framing. Through systematic filtering and selective emphasis, mass media “manufactures consent” by shaping public perception to align with elite interests while maintaining an illusion of objective reporting. This analysis provides a powerful tool for understanding media bias not as isolated instances but as a structural feature of the system.

“Manufacturing Consent” remains essential reading for understanding modern coverage of conflicts and humanitarian crises in the Middle East and beyond. It helps readers recognize both the tactics of media bias – from selective coverage to manipulative language – and their underlying purpose of serving elite interests. By exposing these patterns, the book enables readers to understand how media framing perpetuates rather than challenges existing power structures.