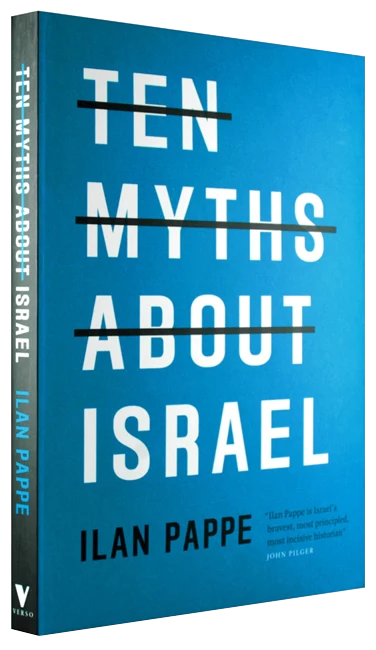

BOOK REVIEW: Ten Myths About Israel

Ilan Pappe

2017

In this groundbreaking book, originally published on the fiftieth anniversary of the occupation, the outspoken Israeli historian Ilan Pappe examines the most contested ideas concerning the origins and identity of Israel. Pappe, a historian, identifies ten fundamental myths which are discussed in separate chapters. The analysis incorporates a historical framework, its absorption by the international community and its repercussions upon Palestinian memory and the scarce options available for anti-colonial struggle and autonomy.

In this groundbreaking book, originally published on the fiftieth anniversary of the occupation, the outspoken Israeli historian Ilan Pappe examines the most contested ideas concerning the origins and identity of Israel. Pappe, a historian, identifies ten fundamental myths which are discussed in separate chapters. The analysis incorporates a historical framework, its absorption by the international community and its repercussions upon Palestinian memory and the scarce options available for anti-colonial struggle and autonomy.

The “ten myths” that Pappe explores—repeated endlessly in the media, enforced by the military, accepted without question by the world’s governments—reinforce the regional status quo. Pappe explores the claim that Palestine was an empty land at the time of the Balfour Declaration, as well as the formation of Zionism and its role in the early decades of nation building. He asks whether the Palestinians voluntarily left their homeland in 1948, and whether 1967 was a war of “no choice.” Turning to the myths surrounding the failures of the Camp David Accords and the official reasons for the attacks on Gaza, Pappe explains why the two-state solution is no longer viable.

Pappe begins by admitting that, “This is not a balanced book; it is yet another attempt to redress the balance of power on behalf of the colonized, occupied and oppressed Palestinians in the land of Israel and Palestine.” The first myth which is confronted is the Zionist claim that Palestine was an empty land when they arrived. Pappe explains, “Outside of Israel, in particular in the US, the assumption that the promised land was empty, desolate, and barren before the arrival of Zionism is still alive and kicking…Palestine began to develop as a nation long before the arrival of the Zionist movement. In the hands of energetic local rulers such as Daher al-Umar (1690-1775), the towns of Haifa, Shefamr, Tiberias, and Acre were renovated and re-energized. The coastal network of ports and towns boomed through its trade connections with Europe, while the inner plains traded inland with nearby regions.” At the end of the 19th century, Palestine had a sizable population, of which only a small percentage was Jewish. Those Jews who did live in Palestine at this time were opposed to the ideas promoted by Zionism. Contrary to the notion of Palestine being an “empty land,” Pappe shows that, “It was part of a rich and fertile eastern Mediterranean world that in the 19th century underwent processes of modernization and nationalization.”

The second myth Pappe considers is that “The Jews Were a People Without a Land.” He asks whether the Jewish settlers who arrived in Palestine could be considered “a people,” Pappe cites Shlomo Sand’s “The Invention of the Jewish People,” which shows that the “…Christian world, in its own interest, adopted the idea of the Jews as a nation that must one day return to the holy land. This return, in their view, would be part of the divine scheme for the end of the world, along with the resurrection of the dead and the second coming of the Messiah. Zionism.” Pappe believes this “…was therefore a Christian project of colonization before it became a Jewish one… A powerful theological and imperial movement emerged that would put the return of the Jews to Palestine at the heart of a strategic plan to take over Palestine and turn it into a Christian entity… This dangerous blend of religious fervor and reformist zeal…would lead to the Balfour Declaration of 1917.”

Pappe believes it was British strategic interests rather than their sentiment for the Jews that led them to support Zionism. An important advocate of a Jewish return to Palestine in England in the 19th century was Lord Shaftesbury (1801-85), a leading politician and reformer, who campaigned actively for a Jewish homeland in Palestine. In 1839, Shaftesbury wrote a 30-page article in The London Quarterly Review in which he predicted a new era for the Jews: “…the Jews must be encouraged to return in yet greater number and become once more the husbandman of Judea and Galilee…though admittedly a stiff-necked people and sunk in moral degradation, obduracy, and ignorance of the Gospel, (they are) not only worthy of salvation but also vital to Christianity’s hope and salvation.” Pappe believes Zionists had to rely on British officials and, later, military power. Jews and the world at large were not convinced that the Jews were a people without a land. Shaftesbury, Finn, Balfour, and Lloyd George liked the idea because it helped Britain gain a foothold in Palestine. This became immaterial after the British took Palestine by force and then had to decide from a new starting point whether the land was Jewish or Palestinian—a question it could never properly answer, and therefore had to leave to others to resolve after 30 years of frustrating rule.

Pappe questions whether the Jews who settled in Palestine as Zionists were really the descendants of the Jews who had been exiled 2,000 years ago. Quoting Arthur Koestler (1905-83) who in “The Thirteenth Tribe” (1976) advanced the theory that the Jewish settlers were descended from the Khazars, a Turkish nation of the Caucasus which converted to Judaism in the 8th century and was later forced to move westward.

The third claim Pappe looks at is Israel’s claim to represent all Jews – Zionism is Judaism and that everything it does is for their sake and on their behalf. Pappe highlights Zionism was originally a minority opinion among Jews. “Since its inception in the mid-19th century Zionism was only one, inessential expression of Jewish cultural life. It was born out of two impulses among Jewish communities in Central and Eastern Europe. The first was a search for safety within a society that refused to integrate Jews as equals and that occasionally persecuted them… The second impulse was a wish to emulate other new national movements mushrooming in Europe at the time.” Zionism gained some support in countries such as Russia, where Jews were second-class citizens, Pappe however explains that, “As these early Zionist ideas were aired among Jewish communities in countries such as Germany and the US, prominent rabbis and leading figures in those communities rejected the new approach. Religious leaders dismissed Zionism as a form of secularisation and modernisation, while secular Jews feared that the new ideas would raise questions about the Jews’ loyalty to their own nation-states and would thus increase anti-Semitism.” In 1897, the same year as the first Zionist conference was convened in Basel, Switzerland, a socialist Jewish movement was born in Russia, the Bund. Bund members believed that a socialist revolution would be a far better solution to the problems of Jews in Europe than Zionism.

Another critique of Zionism came from Orthodox Jews. Pappe notes that, “When Zionism made its first appearance in Europe, many traditional rabbis in fact forbade their followers from having anything to do with Zionist activists. They viewed Zionism as meddling with God’s will to retain the Jews in exile until the coming of the Messiah.” Pappe notes, “…it also hoped to secularize the Jewish people, to invent the ‘new Jew’ in antithesis to the religious Orthodox Jews of Europe… The Orthodox Jew was ridiculed by the Zionists, and was viewed as someone who could only be redeemed through hard work in Palestine.”

Another myth which Pappe confronts is, “Zionism Is Not Colonialism.” Pappe argues Zionism was a settler colonial movement, similar to the movements of Europeans who had colonised the two Americas, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Settler colonialism is motivated by a desire to take over land in a foreign country, while classical colonialism covets the natural resources in its new geographic possession. The problem was that the new ‘homelands’ were already inhabited by other people. In response, the settler communities argued that the new land was theirs by divine or moral right, even if, in cases other than Zionism, they did not claim to have lived there thousands of years ago. In many cases, the accepted method for overcoming such obstacles was the genocide of the indigenous locals.

In Pappe’s view, “One can depict Zionism as a settler colonial movement and the Palestinian national movement as an anticolonial one…. By 1945, Zionism had attracted more than half a million settlers to a country whose population was about 2 million… The settlers’ only way of expanding their hold on the land…and of ensuring an exclusive demographic majority was to remove the natives from their homeland… Palestine is not entirely Jewish demographically, and although Israel controls all of it politically by various means, the state of Israel is still colonising—building new settlements in the Galilee, the Negev, and the West Bank…”

Other myths confronted by the author include: the 1967 war was a war of “no choice,” Israel is the only democracy in the middle east, the Oslo mythologies, the Gaza mythologies and the two-states solution is the only way forward. A just solution to the dilemma of Palestine will, Pappe concludes, only be achieved if we stop treating the mythologies he sets forth as truths.

Pappe’s book is methodical, presenting facts with precision in a historical timeline. Pappe challenges Israeli narratives through facts which Israel and the international community have striven to wipe out and manipulate. Pappe does a very good job at highlighting the historical background to many of the arguments and provides lots of evidence showing their roots, evolution and how they are used to justify occupation.