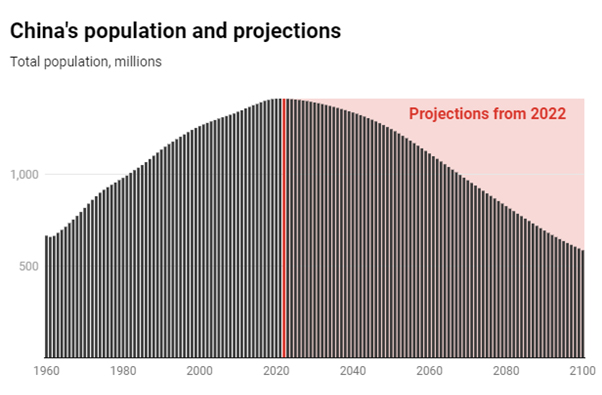

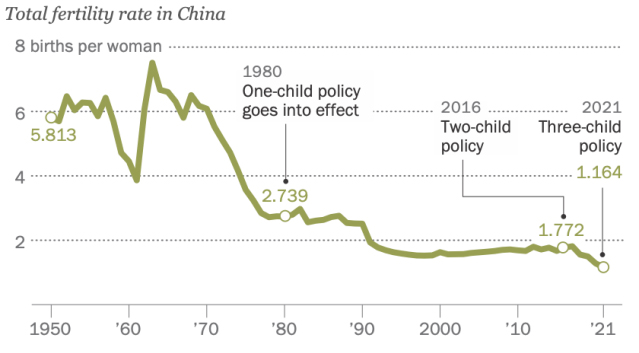

China’s National Bureau of Statistics released the countries’ latest demographic numbers on Tuesday the 17th January, confirming China’s population fell for the first time since records began back in 1953. The world’s most populated nation saw its demography shrink by 850,000 people as its replacement rate fell to 1.15 children per woman, well below the replacement rate of 2.1. China’s birth rate has been declining for years and prompted a slew of policies to try to slow the trend. But seven years after scrapping the one-child policy, China has entered a new era of negative population growth.

Since 2021 when China published results from its once-a-decade census it showed China’s population growing at its slowest pace in decades with newborn babies falling by 20% from 2019. It was expected China would not see population decline for at least another decade. But the arrival of population decline poses a major strategic challenge for China who for long relied upon an endless supply of young workers to fuel its economic growth.

It was expected China would not see population decline for at least another decade. But the arrival of population decline poses a major strategic challenge for China who for long relied upon an endless supply of young workers to fuel its economic growth

The numbers released from the National Bureau showed the country’s population is now 1.4118 billion, falling by 850,000 lower than 2021. Chinese population growth has been shrinking for a decade and now it has turned negative. This is the first time this has happened since records began after WW2 when the Communist Party conducted its first census, in 1953. The birth rate of babies has been declining for a decade, but it now reached its lowest official number since 1961, when the great leap forward caused widespread famine. The only aspect of China’s demography that is growing are those in retirement. The population is ageing rapidly with 264 million pensioners. China is growing old without first having grown rich.

China abandoned its one child policy in 2015 as after three decades the policy led to a huge gender imbalance and an inverted population pyramid where a diminishing pool of young workers came to support an ever-increasing number of pensioners. The One Child Policy, adopted in 1979 was in order to avoid massive overpopulation. As a result of this policy China’s fertility rate has fallen to 1.15 children per woman, when 2.1 children per woman is needed to maintain a stable population.

The effects of the One Child Policy can be felt across China. A Ministry of Education report in August 2018 confirmed more than 13,600 primary schools closed nationwide in 2012. The ministry looked to China’s dramatically shifting demographic profile to explain the widespread closures, noting that between 2011 and 2012 the number of students in primary and secondary schools fell from nearly 150 million to 145 million. It also confirmed that between 2002 and 2012, the number of students enrolled in primary schools dropped by nearly 20%.

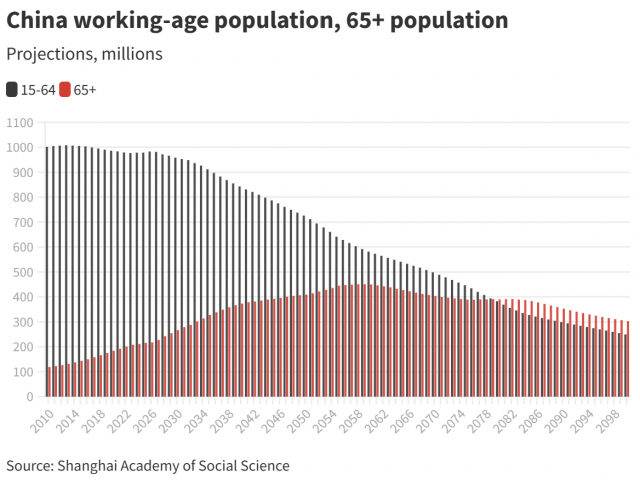

Considering China’s large population one would think a slowing or even shrinking of the population is a positive development. But for China the declining population comes at the wrong time. If China wants to continue its economic growth she will need to urbanise much more of its population to increase domestic consumption. It will need to house, employ, care for and educate most of its population if it hopes to create more consumers by 2030. Within the next decade however, over 25% of China’s population will be over the age of 60, compared with around 13% today. In that time, the portion of China’s population too young or too old to work will rise from around 38% to 46%, with the balance of China’s dependent population shifting substantially from young to old. At the same time, China’s working-age population (20-59) is set to decline by as much as 80 million people. The shift to internal consumption will require a drastic increase in worker productivity just to sustain growth rates even remotely close to present levels.

“China is facing a unique demographic challenge that is the most urgent and severe in the world,” said Liang Jianzhang, a research professor of applied economics at Peking University and a demography expert. “This is a long-term time bomb.” As China’s population gets older, it will impose immense pressure on the country’s social system and underfunded pension system. China also continues to grapple with a huge surplus of single men that has driven problems such as bride trafficking.[1]

Like a number of other nations facing demographic decline, raising the retirement age is being considered by the Communist Party. China has a retirement age for women of 50 and men at 60 years. China’s main state pension fund, which relies on tax revenues from its workforce, risks running out of money by 2036.

China’s huge and endless supply of workers was the backbone of its economic growth for four decades. Whilst China has been looking to shift away from cheap, low end manufacturing to high end and high value manufacturing that will rely more on technology rather than workers, China needs its large population to consume much of what it will produce. With China’s workforce shrinking, this will mean its consumer base will also shrink and this will likely pose one of the most serious challenges to the Chinese communist Party.

Whilst the CCP likes to present China’s exports, aircraft carriers, smart cities, bullet trains and AI as signs of its superpower status, the truth is China has a growing list of internal challenges, such as Taiwan, Hong Kong, Xinjiang, its economic model and now population decline. All of these indicate that China’s future will be determined by its internal issues rather than what it projects abroad. India will also be replacing China as the world’s largest nation in June.

[1] She Thought She’d Married a Rich Chinese Farmer. She Hadn’t. – The New York Times (nytimes.com)