For several centuries, Russian leaders have looked across every direction from their vast landscape that encompasses 11 time zones and formulated policy accordingly: but no direction has concerned Russia more than westwards. Western leaders seem to have difficulty deciphering Putin’s motives, especially when it comes to his actions in Ukraine; his invasion towards Kiev has shocked the world. Russia’s current leader has been described in terms that evoke Winston Churchill’s famous 1939 observation that Russia “…is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside of an enigma.” But few go on to complete the sentence, which ends, “…perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest.”

It’s helpful to look at Putin’s military intervention in the context of Russian leaders’ longstanding attempts to deal with geography. What if Putin’s motives are not so mysterious after all? What if you can read them clearly on a map?

Geography

For Russia, the world’s largest country by landmass, which bestrides Europe and Asia and encompasses forests, lakes, rivers, frozen steppes, and mountains, the problems come by land as well as by sea. In the past 600 years, Russia has been invaded every century from the west. The Ottomans burnt Moscow to the ground in 1571, the Poles came across the European Plain in 1605, followed by the Swedes under Charles XII in 1707, the French under Napoleon in 1812, and the Germans—twice, in both world wars, in 1914 and 1941. [1]

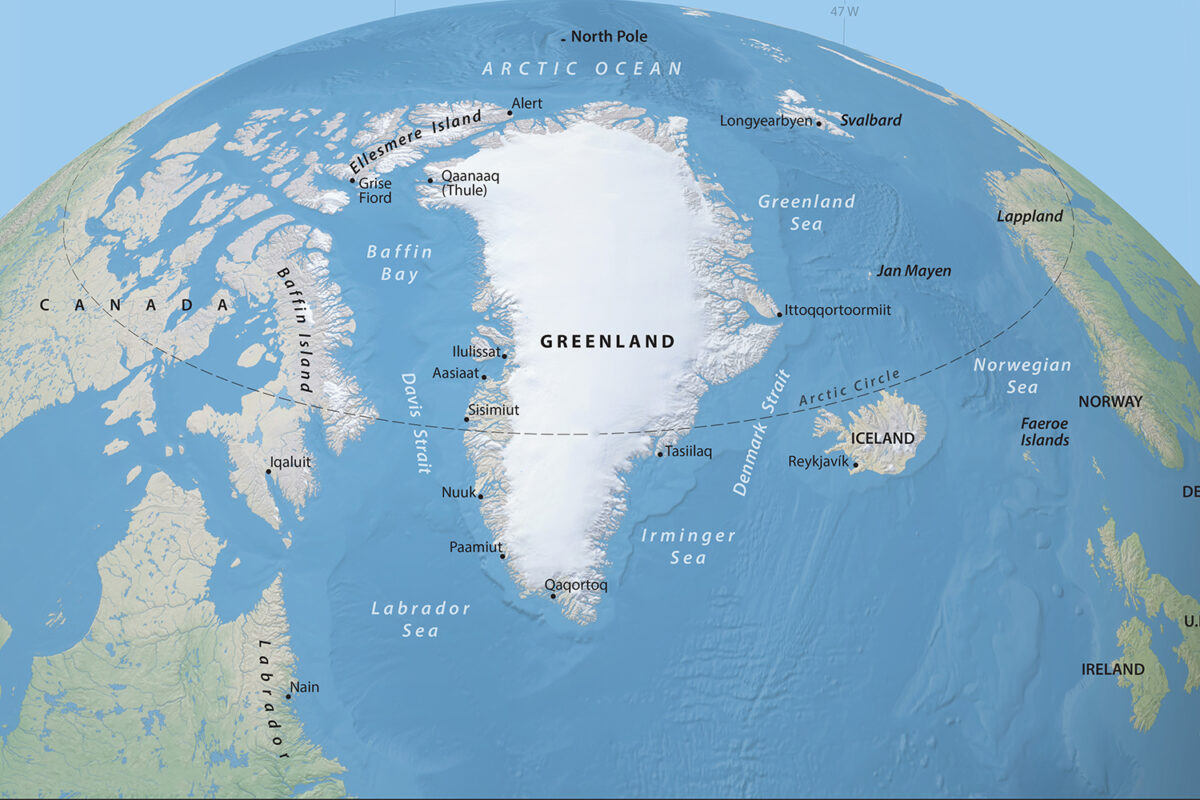

In Poland, the plain is only 300 miles wide—from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Carpathian Mountains in the south—but after that point it stretches to a width of about 2,000 miles near the Russian border, and from there, it offers a flat route straight to Moscow. To put simply, from 1812 to 1945, the Russians were fighting on average in or around the North European Plain once every thirty-three years and its current borders leave it exposed.

Thus Russia’s repeated attempts to occupy Poland throughout history; the country represents a relatively narrow corridor into which Russia could drive its armed forces to block an enemy advance toward its own border, which, being wider, is much harder to defend. With neighbouring Ukraine providing access to warm water ports in Crimea and a supportive, Russian speaking population residing there, Ukraine is part of Russia’s design in the Black Sea: extend the buffer zone.

Cultural History

For Russia, Ukraine’s capital is the cultural and spiritual capital of the Russian people. Going all the way back to Russia’s progenitor state of Kievan Rus of the 10th century, founded by the Rurikid dynasty originating among Swedish vikings, Ukraine has been a part of, or closely connected to, the continuous political entity that we now call “Russia”.

Although there were periods where statelets in contemporary Ukrainian territory fell outside of formal Russian control, and even became part of Islamic rule for centuries under the Golden Horde and as a satellite of the Ottoman Caliphate, Ukraine never completely left “Russian” hegemony and culture since the 1000s and was formally reinstated into the Russian empire since the 18th century. While this does not give Russia a right to the territory in a legal or moral sense, it helps explain the attachment Russians have for a land they believe is intimately connected to them.

The NATO question

At the end of WWII, the Russians occupied territory conquered from Germany in Central and Eastern Europe and the USSR, consisting of 15 republics — the lands began to resemble the old Russian Empire again.

In contrast, in 1949 the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) was formed by an association of European and North American states, for the defence of Europe and the North Atlantic against the danger of Soviet aggression.

To counter this, most Communist states of Europe – under Russian leadership – formed the Warsaw Pact, a treaty for military defence and mutual aid. But with the fall of the Soviet Union, the Pact also disintegrated in 1991.

President Putin lamented this historic moment – consequently, he is no fan of the last Soviet President, Mikhail Gorbachev. He blames him for undermining Russian security and has referred to the break-up of the former Soviet Union as ‘a major geopolitical disaster of the century’.

Since 1991 the Russians have watched anxiously as NATO has crept steadily closer, incorporating countries which Russia claims it was promised would not be joining; the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland in 1999, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania and Slovakia in 2004 and Albania in 2009. NATO says no such assurances were given.

While the current confrontation between Russia and the West is fuelled by many grievances, for Russians, “the Betrayal” is considered the greatest grievance of them all. In his now famous 2007 speech to the Munich Security Conference and the run up to the recent Ukraine invasion, Putin accused the West of forgetting and breaking assurances, leaving international law in ruins.

Tensions were already high when, upon the inauguration of US President Joe Biden in 2020, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said his first question to the new US leader would be: “Mr President, why are we not in NATO yet?” [2]

Continued cooperation between Ukraine and NATO had put Ukraine in a strong position to join the defence alliance and plans were already in place for this to happen. Ukraine, along with Georgia, began a formal process to begin a NATO Membership Action Plan (MAP) in 2008.

This led Russia to ask for assurances that a neighbouring country like Ukraine does not join NATO but had the demand rejected by the West. Speaking previously, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said: “It’s only Ukraine and 30 NATO allies that decide when Ukraine is ready to join NATO. Russia has no veto, Russia has no say, and Russia has no right to establish a sphere of influence to try to control their neighbours.” [3]

Clearly, Putin did not share the same sentiment as he attempted to counter Western efforts to wrestle control of Ukraine through their support for the Orange Revolution in 2004 and then the Euromaidan Revolution in 2014. For the West, the purpose of these coups was to absorb Ukraine into the EU, indirectly rendering it a NATO asset, and of course reducing its utility as a Russian market. From that moment the die was cast. Putin annexed Crimea, which contained not only many Russian-speaking Ukranians but, most importantly, the port of Sevastopol. And with Ukraine and NATO’s insistence on aspiring membership throughout the COVID19 pandemic, Russia has now taken the decision to declare regions of Ukraine independent and move troops into these regions.

The two decades have seen many decisive moments: a lack of appetite in the West for war after their abysmal “War on Terror” campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, Western economies in tatters after the financial crisis of 2008 and losses incurred during the Covid pandemic, a lack of confidence among EU states after Brexit with the rise of nationalist parties and the US’s focus on China — perhaps now Putin sensed an opportunity.

What Now?

It would appear Russia wants regime change and this may be with a divided Ukraine or a combined Ukraine (which looks unlikely for the moment). Putin will expect at least a return to Ukraine’s Minsk agreement with Russia which consisted of a package of measures, including a ceasefire, withdrawal of heavy weapons from the front line, release of prisoners of war, constitutional reform in Ukraine granting self-government to certain areas of Donbas and restoring control of the state border to the Ukrainian government as well as complete rejection of NATO membership.

In reality, a situation reminiscent of the aftermath of the Iraq War could play out if the conflict evolves into Russia fighting an insurgency supported by NATO. There is a developing perception that the war will not stop until Ukraine is conquered or divided, or has put an end to the western espansion to the East.

Ultimately, Russia has not finished with Ukraine yet, nor elsewhere. Unless it feels threatened, Russia will probably not send its troops all the way into the Baltic states, or any further than it already is in Georgia, and in this volatile period further military action cannot be ruled out. But how Russia responds to the fallout from the invasion is the first major challenge it faces today.

[1] Russia and the Curse of Geography, From Ivan the Terrible to Vladimir Putin – The Atlantic

[2] Zelenskiy asks Biden why Ukraine still not in NATO – EURACTIV.com

2 comments

Václav

3rd March 2022 at 5:05 pm

The article contains at least two inaccuracies.

1) Warsaw is much further west than the map shows.

2) Furthermore, it is not true that Ukraine has been part of Russia since the 10th century. At that time, Moscow did not even exist, and therefore not the Russian state in today’s sense of the word. Moscow has no right to claim the Ukrainian nation. You may better understand that it is as if Poland claims the Czechia, Slovakia and other southern Slavic nations. Almost every one of these nations once had its “empire.” The borders as Putin wants and paints them are the borders of the empire. At the same time, the current Russian borders are imperial. There are many nations in Russia who are denied the right to self-determination.

Václav

3rd March 2022 at 5:15 pm

3rd inaccuracy is the tone of the Orange Revolution. That happened, because someone, guess who, poisoned their presidential candidate and then there was a meddling in their votes.