By Adnan Khan

On Christmas eve, dawn raids took place across Turkey, implicating three government ministries, the directors of state banks and some of Turkey’s most powerful businessmen in a massive corruption probe.[1] In what is now the biggest scandal since the AKP rose to power in 2002, three ministers were forced to resign as their sons were among dozens of people detained as part of a wide-ranging corruption probe.[2] With local municipal elections due in March 2014, Presidential elections due in June 2014 and Parliamentary elections due in June 2015, questions are being raised on whether the AKP’s grip on power is coming to an end. The current scandal is the result of an on-going souring of relations within Erdogan’s support base, which has now come out into the open.

The recent events may be understood in light of the following:

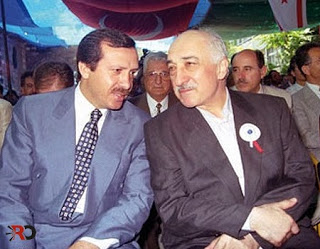

Firstly when Erdogan and the AKP took power in 2002, it was in a climate of crisis as the previous coalition government had collapsed. The army, judiciary and secular opposition maintained their influence despite the AKP winning a clear majority. The AKP immediately set about weakening the hold of the army and the secular opposition through constitutional amendments,[3] through altering the make-up of the National Security Council[4] and through corruption probes against those who could potentially threaten the AKP.[5] The AKP gave the domestic police more powers and military grade weapons to counter the army, and created a new breed of business class through a massive government privatization campaign totalling over $54 billion.[6] The AKP rise also included an alliance with the Fethullah Gülen Movement (FGM).

Secondly, the Gülen movement is a worldwide religious organization, educational network, and business conglomerate rooted in Turkey. The organization bears the name of an Islamic scholar and cleric who began preaching and developing a wide-ranging network in Turkey in the 1970s, and has resided in the US since 1999. The movement began penetrating Turkey’s law enforcement in the 1970s, and their influence reached its peak under the AKP. Today the Güllenists have people in various influential positions of society, which include teachers, journalists and police chiefs. Facing a state apparatus that had been traditionally hostile towards Islamic minded individuals, Erdoğan chose to assign a number of official positions to Gülen members to cement his influence in the state institutions. The FGM proved very useful in Erdoğan’s showdown with the secular elements within the state institutions and judiciary. The FGM controlled news outlets that eagerly published allegations leaked from court proceedings related to the Ergenekon and Sledgehammer cases, which resulted in weakening the positions of Erdoğan’s opponents .[7]

Thirdly, relations between Erdoğan and Fethullah Gülen soured after Gülen’s criticism of Erdoğan’s handling of the Turkish flotilla incident.[8] The FGM, with its sheer size and influence, continued to undermine Erdoğan, which in turn also led Erdoğan to put them in check and also undermine them.[9] In the 2011 general elections the FGM nominated its own members to the electoral lists for the AKP, but Erdoğan fielded other party loyalists.[10] This was when the fallout became public and FGM media outlets began to openly criticize Erdoğan’s policies. In response, Erdoğan deposed a number of security officials affiliated with the group, to ensure it did not penetrate and gain more control of state institutions. Erdoğan then announced in November 2013 the nationalisation of private preparatory schools, one of the FGM’s most important operations and sources of income. This was taken as a declaration of war by the Güllenists who ran 25% of all such schools in Turkey.[11] The Güllenists lashed out in response, leaking a torrent of compromising material on the AKP and Erdoğan.

Fourthly, the FGM in its latest move began corruption cases against those who benefited from AKP rule and received kick-backs. The FGM utilised its media outlets to highlight the arrests, which included individuals from Erdoğan’s inner circle. All of this was to expose and weaken Erdoğan. The AKP government’s immediate reaction was to initiate a country-wide comprehensive overhaul of the Turkish Police Force. Consequently, dozens of senior police officers, including the Istanbul police chief, were removed from their posts and assigned to other positions outside the probe.[12] The FGM exposed the fact that secret talks had been taking place with the PKK since 2003, additionally, documents were also leaked that the government had been using the state’s intelligence agency, MIT, to gather information on opposition-leaning businessmen.

After a decade long rule, Erdoğan successfully challenged the army and won, and he was as successful in weakening the secular elements in the judiciary and the opposition. However, 2013 has been a difficult year for Erdoğan, especially with the Taksim Square protests in June 2013. Will Erdoğan survive? Erdoğan is still popular amongst a large segment of the Turkish population and is considered to have administered Turkey’s economy particularly well. The mounting pressure against Erdoğan has not reached the point where a significant number of AKP members view him as a liability. Erdoğan is a politician first and foremost, and has thus far weathered the storm against him. Creating new political alliances to compensate for the Güllenist support will in all likelihood help the AKP win the upcoming elections. Erdoğan is expected to remain on the Turkish political scene for years to come.

[4] A quiet revolution: Less power for Turkey’s army is a triumph for the EU, Financial Times (editorial), July 31, 2003.

[7] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-24457491 and http://www.gloria-center.org/2011/08/ergenekon-sledgehammer-and-the-politics-of-turkish-justice-conspiracies-and-coincidences/

[9] http://www.todayszaman.com/columnists/emre-uslu_332737-did-erdogan-say-shut-up-to-gen-eruygur.html