|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Yusuf Abu Sinan

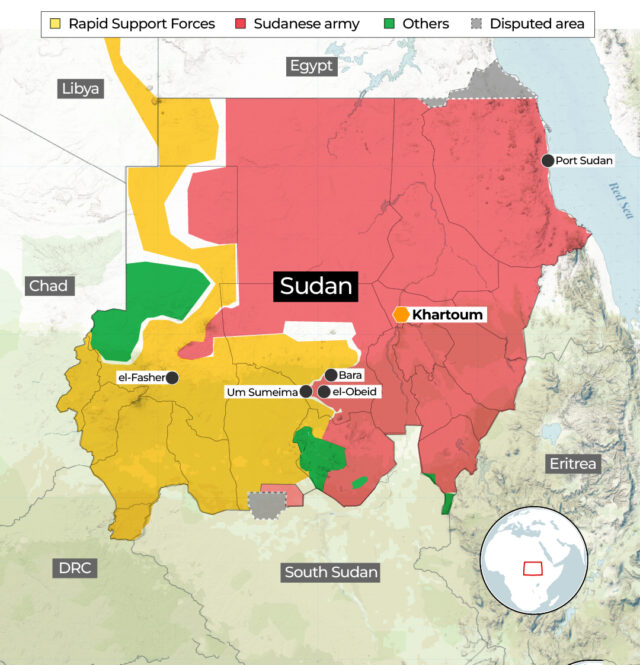

Sudan has returned to the headlines as the fall of el-Fasher — the capital of Darfur — exposes scenes of mass killing visible even from satellite imagery. On October 26, 2025, after a two-year siege, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) captured the headquarters of the Sudanese Armed Forces’ (SAF) 6th Infantry Division, completing their takeover of the city.

The 534-day siege of el-Fasher left famine, disease, and mass displacement in its wake, but the week that followed its fall brought horrors compared by witnesses to a Mongol-style slaughter. Western media has finally taken notice, highlighting what Sudanese citizens have long known — that the RSF’s rule brings systematic destruction. The only real surprise, many Sudanese note bitterly, is that anyone is surprised.

The fall of el-Fasher raises several questions: How did it happen? Why did it happen now? And why has Western attention suddenly surged? To answer these, we must trace the roots of Sudan’s fractured power structure.

From el-Bashir’s Regime to a Fractured State

Omar el-Bashir came to power in 1989 through a coup backed by the Islamic Movement led by Hassan al-Turabi. He consolidated his control over the armed forces and ruled for 30 years through repression and manipulation, balancing Islamist rhetoric with pragmatic alliances. His regime oversaw a brief economic boom before decades of sanctions, corruption, and mismanagement set in.

The conflict in South Sudan was his undoing. Facing rebellion over land, oil, and autonomy, el-Bashir cooperated with the United States to broker the secession of South Sudan in 2011, even when his army held the upper hand. But the loss of oil revenue deepened Sudan’s economic crisis. By 2018, mass protests toppled his rule, and in April 2019, the military replaced him with Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, a relatively obscure figure who became Sudan’s de facto head of state.

Omar el-Bashir came to power in 1989 through a coup backed by the Islamic Movement led by Hassan al-Turabi.

The Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF)

The SAF had always been the real power behind the regime. After the revolution, they reasserted direct military control, sidelining civilians while projecting an image of reform. To placate the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) — the main civilian coalition — the SAF agreed to a three-year transitional arrangement: a hybrid civilian–military government, with Burhan chairing the first half and civilians the second.

But before civilians could take over, Burhan staged a coup, dissolving the government under the pretext of “correcting the revolution’s course.” During this period, he also courted the West and Israel — meeting Netanyahu in Uganda and signing the Abraham Accords — moves that strengthened his position abroad but alienated domestic forces.

Under international pressure, the SAF later signed the Transitional Framework Agreement to transfer authority to civilians. This agreement threatened not only Burhan’s control but also the RSF’s autonomy — setting the stage for war.

The SAF had always been the real power behind the regime. After the revolution, they reasserted direct military control

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF)

The RSF evolved from the Janjaweed militia, notorious for atrocities during the early 2000s Darfur conflict. Originally led by Musa Hilal and later by his cousin Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo (“Hemedti”), the militia was meant to chase down Darfur rebels in remote regions. Over time, it morphed into a paramilitary empire.

El-Bashir relied on Hemedti to guard against army coups, granting the RSF access to Darfur’s gold mines, especially Jebel Amer. The group grew into a semi-autonomous power broker, running gold exports, mercenary operations, and private deals with foreign patrons — notably the UAE, which employed RSF fighters in Yemen and dominated Sudan’s gold trade.

After 2019, Hemedti became Burhan’s deputy, and the RSF helped crush protests outside army headquarters in Khartoum, deepening public resentment. When the 2023 Transitional Framework Agreement threatened their independence, the RSF struck first — launching a coup attempt in April 2023.

Clashes erupted nationwide. The SAF withdrew from major cities, allowing the RSF to roam unchecked. Even as civilians were slaughtered, international mediators called for restraint and “dialogue.” The result was paralysis — and space for the RSF to consolidate its grip on Darfur.

The Darfur Rebel Movements

Two groups — the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM) under Minni Minnawi and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) under Gibril Ibrahim — once fought against Bashir’s regime but later joined it. After the 2023 war began, they initially remained neutral but eventually aligned with the SAF to resist the RSF’s advance.

Their forces heroically defended el-Fasher for over 500 days without reinforcements, but the fall of the city leaves them shattered. If the RSF consolidates control and Darfur moves toward de facto secession, these movements risk political extinction.

The FFC, Taqaddum, and Sumood

The secular-liberal coalition that rose during the 2019 revolution has since splintered. The faction led by former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok — now branded as Sumood — retains strong ties to the UK, Qatar, and the UAE, despite lacking any real base inside Sudan. During its brief time in government, the FFC focused on removing Islamic influences from law and education and normalizing ties with Washington, even paying reparations for the USS Cole attack to ease sanctions.

Since the war began, Sumood has sided with the RSF, adopting an anti-Islamist rhetoric aimed at winning Western sympathy and positioning itself as the “civilian alternative” to the SAF.

Foreign Powers and the Quartet

Since 2019, Sudan’s fate has largely been managed by an informal Quartet: the US, UK, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE. This group mediated the initial transitional deal and later steered the 2023 Framework Agreement. In September 2025, the Quartet was reshaped — the US replaced the UK with Egypt — formalizing a division of roles.

The US directs the diplomatic tempo, portraying the war as a civil conflict between “two equal sides.” Its strategy has been to prolong the conflict, maintaining both forces as counterweights and preserving leverage for a potential partition of Sudan — especially in Darfur.

The UAE arms and funds the RSF while denying it publicly, its motives rooted less in gold than in counter-revolutionary fear: the desire to suppress any Arab uprising that might inspire change at home. The Saudis and Egyptians, meanwhile, support the SAF, but under the same US umbrella, ensuring no side wins decisively.

The UAE arms and funds the RSF while denying it publicly

The UK’s Waning Role

Once a key backer of the FFC, the UK has been sidelined by Washington’s newer alignment with Cairo. British media’s sudden spotlight on el-Fasher’s atrocities reflects London’s attempt to reinsert itself diplomatically — using humanitarian rhetoric as a pretext for renewed involvement.

A War of Many Layers

Sudan today hosts five overlapping conflicts — military, tribal, political, ideological, and international. The fall of el-Fasher is not just a battlefield loss but a symbolic defeat for Sudanese sovereignty.

The Quartet, led by Washington, effectively manages the war’s equilibrium: the UAE sustains the RSF; Egypt and Saudi Arabia prop up the SAF; the US orchestrates both; and the UK agitates from the margins. The goal is not victory or peace but control.

What Comes Next

With Darfur now fully under RSF control, the next phase may well be partition. Washington’s muted reaction to el-Fasher’s fall suggests no urgency to intervene. Instead, it will likely engineer public sentiment to accept a “peace plan” that legitimizes RSF rule in a breakaway Darfur. When the time comes, the US may theatrically “distance” itself from the UAE — portraying itself as a mediator while shepherding Sudan toward a divided future.

The war in Sudan, like those that crushed the Arab Spring, has become a textbook case of how external powers — through local proxies and competing agendas — dismantle a revolution from within.