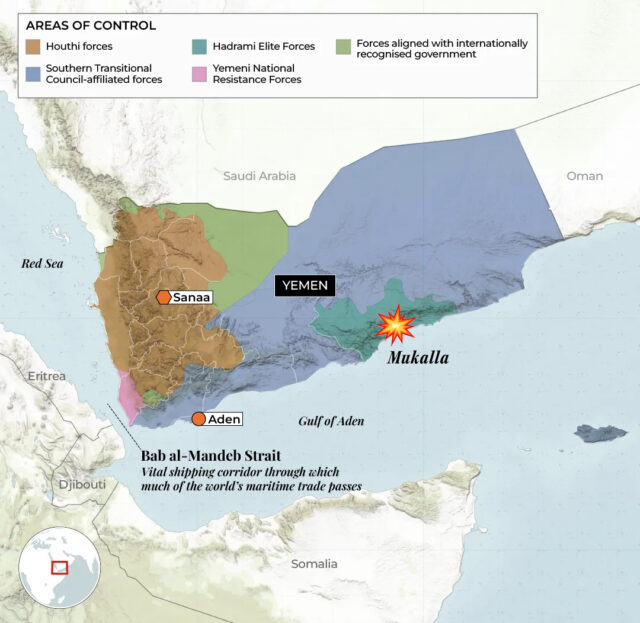

Tensions between the House of Saud, the ruling dynasty of Saudi Arabia, and the Al Nahyan and Al Maktoum families, who dominate political power in the United Arab Emirates, have spilled into open confrontation in Yemen. Saudi aircraft have struck shipments of Emirati arms allegedly bound for the Southern Transitional Council (STC), a UAE-backed secessionist movement seeking the partition of the country.

The deliberate use of dynastic nomenclature is instructive. In states where rule is exercised by families rather than symbolic institutions—as opposed to constitutional monarchies such as Britain—it is the interests of the ruling house that prevail. Public welfare is considered principally through the prism of regime stability, not as an end in itself.

The Gulf monarchies, including Saudi Arabia, owe their modern political configuration to American power and British statecraft. Their foreign policies remain closely aligned with those of their respective patrons. While Riyadh and Abu Dhabi often act in concert where Western interests overlap, Saudi policy is inseparable from Washington’s strategic priorities, while the UAE—despite the overwhelming asymmetry of power between Britain and the United States—remains closely aligned with London.

On December 30th Saudi jets struck storage facilities at Mukalla, the principal port of Yemen’s Hadramout province. According to the Saudi-led coalition, civilian and military vehicles were destroyed after being unloaded from two vessels that had arrived from Fujairah on December 28th. The ships were accused of disabling their tracking systems—a common indicator of illicit activity—and unloading without authorisation from port authorities.

The strikes coincided with a rapid advance by the STC. Since early December, the group has mounted a highly effective offensive against forces loyal to Yemen’s internationally recognised government, seizing large swathes of Hadramout, including the cities of Tarim and Seiyun.

This campaign comes amid growing international acceptance of the STC. Once excluded from the Presidential Leadership Council—the largely symbolic executive body of the Yemeni state—the group was formally incorporated in May 2023, marking a significant shift in Saudi policy towards accommodation rather than outright opposition.

Yemen’s current fragmentation has its roots in the 2011–12 Arab spring uprising, which shattered the precarious post-unification settlement established after 1990. That system distributed power and patronage primarily to northern tribal elites, leaving the south and east marginalised. The resignation of President Ali Abdullah Saleh and the emergence of the Houthis as the de facto rulers of northern Yemen prompted Saudi Arabia and the UAE to intervene militarily, viewing the movement as an extension of Iranian influence.

Yet while Saudi Arabia expended vast sums in an air campaign that frequently failed to achieve decisive results, the UAE pursued a different strategy. Exploiting long-standing southern grievances, Abu Dhabi quietly constructed independent power structures, often operating beyond the authority of both the Saudi-led coalition and the UN-recognised Yemeni government.

Abu Dhabi quietly constructed independent power structures, often operating beyond the authority of both the Saudi-led coalition and the UN-recognised Yemeni government

Emirati engagement against the Houthis was limited. Instead, resources were channelled into cultivating a network of paramilitary forces across southern Yemen, including the Security Belt Forces, the Southern Giants Brigades and the Hadrami Elite Forces—some of which have been implicated in assassinations and enforced disappearances.

Although nominal allies, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi diverge sharply in their ideological outlook. The UAE views the Yemeni government—particularly its Islah faction, which has links to the Muslim Brotherhood—as both a security and ideological threat. It has therefore obstructed efforts to consolidate state authority, favouring instead local armed actors as a counterweight to Islamist influence. This approach culminated in the creation of the STC in 2017, drawing on elements of the former socialist establishment of South Yemen.

Saudi Arabia has adopted a more pragmatic stance. Acknowledging Yemen’s deep ethnic, tribal and religious divisions, Riyadh opposes the formal partition of the country. It envisages a negotiated settlement in which a diminished Iran encourages the Houthis to accept an accommodation within a unified Yemen. The Houthi-controlled north contains the bulk of the population and constitutes the country’s historical heartland. Any durable peace, Saudi officials concede, must include the movement they have been unable to defeat militarily. Southern secession, by contrast, risks entrenching perpetual instability and creating two failed states on Saudi Arabia’s borders.

On religion, Saudi Arabia is as wary of politicised Islam as the UAE, but recognises that Islam remains integral to Yemeni society. Rather than suppress it entirely, Riyadh seeks to contain religious expression within theological, charitable and social frameworks, avoiding overt political mobilisation.

For the UAE, however, the moment appeared decisive. Aydarus al-Zubaydi, the STC’s leader, declared a two-year transitional period, and his forces moved swiftly to establish facts on the ground before Saudi Arabia could offer concessions to the Houthis.

The Saudi response was both swift and uncharacteristically forceful. Rather than relying on economic pressure, Riyadh resorted to military action against Emirati supply lines in Yemen. The result was a rapid reversal of STC gains in Hadramout. Despite its wealth, the UAE lacks the manpower and strategic depth to sustain prolonged conflict against a determined adversary. Its reliance on local proxies—whose loyalties are often transactional— are a critical vulnerability as unlike soldiers motivated by grievance or ideology, mercenaries prefer to spend their earnings rather than dying.

All of this unfolds beneath the protective umbrella of Western patronage. Both the UAE and Saudi Arabia are similar to Ukraine in that they are not capable of using long-range weaponry and their military platforms without foreign targeting support and assistance from the suppliers of the military platforms. This is why it remains inconceivable that Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman would undertake significant military action without American acquiescence, just as it is unlikely that the UAE would pursue its regional ventures without British diplomatic cover.

With the re-entry of Yemeni government forces into Mukalla, the balance has shifted once more. The episode appears to mark the beginning of a reduced Emirati role in Yemen—and a reminder that even among allies, power in the Gulf remains sharply hierarchical.