As the end of 2025 fast approaches this serves as a good opportunity to share some of the favourite books that have informed our analysts.

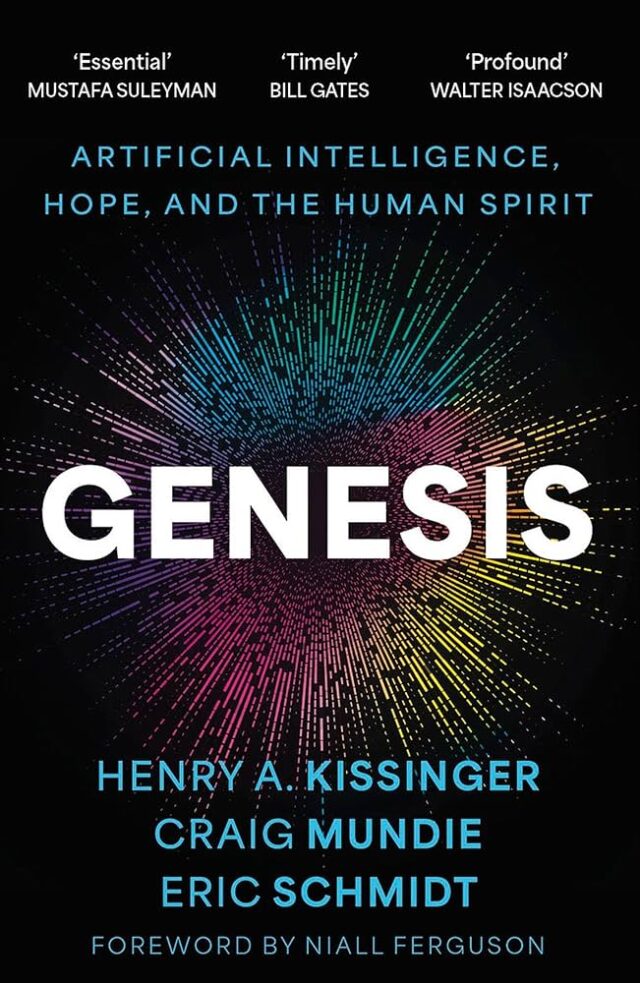

Genesis: Artificial Intelligence, Hope, and the Human Spirit

Craig Mundie, Eric Schmidt & Henry Kissinger

2024

AI is not merely a technological milestone — it is a civilisational rupture forcing humanity to redefine intelligence, agency, and meaning itself.

AI is not merely a technological milestone — it is a civilisational rupture forcing humanity to redefine intelligence, agency, and meaning itself.

Genesis is written by three men who spent their lives in the commanding heights of statecraft, business, and technological innovation, it reads like a final communiqué from an older establishment trying to make sense of forces they helped unleash but no longer fully understand.

The central idea is that artificial intelligence is not simply a tool. It is a new form of cognition. Mundie, Schmidt, and Kissinger argue that modern societies — built on institutionalised decision-making, liberal governance, and human deliberation — are structurally unprepared for systems that process information at scales and speeds that obliterate context and continuity. The book insists that the challenge is not technological but civilisational. For the first time, humanity has created a form of “intelligence” that does not share its evolutionary history, moral frameworks, or emotional architecture.

Kissinger, who passed away in 2023, viewed AI as the first force since the Enlightenment that may fundamentally dissolve the link between truth, perception, and authority. Schmidt adds a Silicon Valley perspective — optimistic, but with the cold realism of someone who knows how fast power accumulates when data trains the machine. Mundie grounds the book in the engineering details, explaining how the architecture of modern AI leads to unpredictability and emergent behaviour.

The authors argue that the “cognitive shock” of AI — the moment societies realise that human judgement has been dethroned — will fracture institutions. If previous technological revolutions reorganised economies, AI will reorganise meaning. That is a much deeper crisis.

Syed Fahad

A World in Permanent Crisis and Wasteland

Robert D. Kaplan

2025

Modern civilisation is entering an age of chronic instability, shaped by geography, demographic breakdown, and the erosion of Western moral and strategic confidence.

Modern civilisation is entering an age of chronic instability, shaped by geography, demographic breakdown, and the erosion of Western moral and strategic confidence.

Robert Kaplan makes a bleak but extraordinarily perceptive argument: the modern world is not heading toward crisis — it is in crisis, and that crisis is permanent.

Kaplan has always been a writer who sees geography not as background but as destiny. In his books, he extends this sensibility into the psychological and political realm. The central idea is: societies today are structurally fragile. Climate stress, water scarcity, demographic collapse, migration waves, and weakened national identities are converging into a long-term instability that no leader or institution is prepared to manage.

Kaplan’s chapters on the Sahel, the Levant, the Balkans, and South Asia read like dispatches from the front lines of a planetary slow-motion implosion. Yet he pairs this with reflections on the West’s internal decay — cultural exhaustion, political cynicism, and the corrosion of civic purpose.

The book combines reportage with a kind of philosophical melancholy. Kaplan believes that the West — especially Europe — no longer has the psychological confidence to shape global affairs. Its moral language is still powerful, but its ability to act is diminishing. Meanwhile, authoritarian states, nationalist movements, and non-state armed groups are filling the vacuum.

Kaplan argues that the world’s crises are no longer discrete episodes but overlapping systems — drought fuels migration, migration fuels nationalism, nationalism fuels political fragmentation, fragmentation prevents coherent climate policy, and the cycle deepens.

Kaplan does not offer solutions.. He strips away illusion and exposes the underlying pressures reshaping the world.

Adnan Khan

Chokepoints: How the Global Economy Became a Weapon of War

Edward Fishman

2025

The global economy — once a tool of integration — has become an arena of conflict where states exploit supply chains, finance, and logistics as instruments of coercion and deterrence.

The global economy — once a tool of integration — has become an arena of conflict where states exploit supply chains, finance, and logistics as instruments of coercion and deterrence.

Chokepoints is about statecraft and Edward Fishman, one of the intellectual architects of modern sanctions policy, makes a clear and unsettling argument: the global economy has become a battlespace, and states are weaponising its arteries — shipping lanes, financial rails, semiconductor chains — with increasing precision.

Fishman’s core argument is that economic integration has flipped. Where globalisation once created incentives for peace, it now creates vulnerabilities that great powers exploit. The US weaponises the dollar system. China weaponises supply chains. Russia weaponises energy. Even minor states exploit narrow bottlenecks — from rare earths to Red Sea shipping corridors — to influence world politics.

The book’s positive aspect is that it’s from inside the machinery. It explains how sanctions are designed, how they bypass traditional war thresholds, how companies and banks become unwilling instruments of statecraft, and how governments now think about supply chains as military assets.

Fishman’s most provocative argument is that the West may be accelerating the collapse of the global system it built. Aggressive use of sanctions, export controls, and financial blacklists is incentivising China, Russia, Iran, and many non-aligned states to build parallel systems. The result is a fragmented world economy — slower, more regionalised, and more hostile.

Chokepoints explains the real terrain of 21st-century great power conflict, where influence is exerted not through armies but through trade networks and container ports.

Umar Ahmed

Reportage: Essays on the New World Order

James Corbett

2025

The modern world is shaped by hidden power structures — financial, political, and informational — that operate beneath official narratives and erode democratic oversight.

The modern world is shaped by hidden power structures — financial, political, and informational — that operate beneath official narratives and erode democratic oversight.

James Corbett is a heavy weight of the alternative media and in this book in a collection of essays he challenges the official stories of our time, exposing the dense web of influence that links intelligence agencies, multinational corporations, financial institutions, and political elites. Whether one agrees with every argument is beside the point. Corbett’s value lies in forcing you to acknowledge that geopolitics has always had a shadow layer.

His central argument is that the modern international system is increasingly opaque, and that democratic oversight has eroded in the face of institutional complexity. Corbett examines NATO interventions, financial secrecy networks, propaganda systems, and the “deep state” dynamics that shape policy behind closed doors.

What stands out in this collection is Corbett’s insistence that power has migrated away from governments and toward networks — intelligence bureaucracies, central banks, big tech platforms, and media conglomerates. His essays argue that these networks do not merely influence policy; they are policy.

This is the kind of book that challenges the assumptions of mainstream geopolitics. Even if one rejects parts of Corbett’s worldview, the questions he asks remain important: Who benefits? Who decides? Who is accountable?

Adnan Khan

Why Civil Resistance Works

Erica Chenoweth

2012

Nonviolent resistance movements succeed more often than violent ones because they generate broader participation, legitimacy, and elite defections — the real engines of political change.

Nonviolent resistance movements succeed more often than violent ones because they generate broader participation, legitimacy, and elite defections — the real engines of political change.

Chenoweth’s argument remains one of the most counterintuitive ideas in political science: mass nonviolent movements succeed roughly twice as often as violent revolutions. In this book, Chenoweth uses historical data to overturn long-held assumptions about how power changes hands.

Her central point is that nonviolent movements create conditions states struggle to manage: scale, legitimacy, and defections. More people participate because the barriers to entry are lower. Legitimacy masks repression. And elites defect more easily when movements appear civic rather than insurgent.

But reading this book in 2025 is different from reading it in 2011. The technological landscape has changed. States have developed far more sophisticated digital repression tools — predictive policing, internet shutdowns, mass surveillance, and online propaganda. Chenoweth’s data remains powerful, but the battlefield has shifted.

Yet the book’s relevance endures because it provides the conceptual foundation for understanding people power. From Belarus to Iran, Sudan to Hong Kong, Chenoweth’s framework explains why movements rise — and why they sometimes fall short.

Her argument forces a valuable reflection: the ultimate terrain of political struggle is legitimacy. And that cannot be manufactured by force.

Abdul Latif

Enough Already: Time to End the War on Terrorism

Scott Horton

2021

The War on Terror was a strategic catastrophe — unnecessary, counterproductive, and corrosive to both American power and global stability. It must end, not be managed.

The War on Terror was a strategic catastrophe — unnecessary, counterproductive, and corrosive to both American power and global stability. It must end, not be managed.

Scott Horton writes with the fire of a man who has spent two decades documenting a tragedy that almost everyone prefers to ignore. Enough Already is not an academic book, and it is not meant to be balanced in the conventional “foreign policy” sense. It is an indictment — a long, exhaustively sourced, moral indictment — of America’s War on Terror and the bipartisan machinery that enabled it.

Horton’s central argument is devastating: the War on Terror created the very monsters it sought to destroy. Every intervention, every drone strike, every coup-backed operation sowed the seeds for new conflicts, new extremist movements, and new resentments. In Horton’s telling, al-Qaeda was a fringe network before 2001. After two decades of “counterterrorism,” the US helped generate al-Qaeda affiliates across the Middle East, expanded ISIS’s footprint, destabilised entire states, and transformed drone warfare into a global norm.

This book is refreshing precisely because Horton engages the geopolitical consequences without hiding behind strategic euphemisms. He is brutally honest about the structural rot inside the US national security state: the financial incentives, the bureaucratic inertia, the political cowardice. His chapters on Libya, Yemen, Somalia, and especially Afghanistan illustrate the sheer cost of US hubris. He argues that terrorism became a justification for endless interventions, each of which deepened the insecurity it claimed to fight.

What makes the book powerful is that Horton isn’t simply anti-war — he’s arguing for strategic realism. The War on Terror, in his view, destroyed American credibility, empowered rivals like Iran and China, and distracted the US from the actual geopolitical contests that matter. His thesis is that America’s greatest self-inflicted wound this century was the decision to fight an abstract enemy with limitless tools and no strategic vision.

Anam Sultan

How Tyrants Fall: And How Nations Survive

Marcel Dirsus

2024

Dictatorships collapse through elite fracture, institutional decay, and regime miscalculations — not through external pressure or popular uprisings alone.

Dictatorships collapse through elite fracture, institutional decay, and regime miscalculations — not through external pressure or popular uprisings alone.

Marcel Dirsus has written one of the clearest, most accessible books on authoritarian breakdown. How Tyrants Fall isn’t a moral critique of dictatorships; it is a structural one. Dirsus’ core argument is that authoritarian systems are inherently brittle, even when they appear stable. Their collapse is rarely due to economic crisis or mass protest alone. It occurs when elites splinter, security apparatuses hesitate, and the regime loses its internal coherence.

What makes this book stand out is its method. Dirsus combines political science research with textured historical case studies — from the fall of Ceaușescu to the Arab Spring, from Franco’s Spain to the collapse of the Soviet Union. He avoids simplistic narratives. Instead, he focuses on the real mechanism of regime failure: internal politics among generals, business elites, party officials, and intelligence chiefs.

Dirsus’ central insight is that authoritarian regimes fail because they rot from within. Leaders over-centralise power, eliminate competent advisors, and distort information flows. Over time, the system becomes incapable of self-correction. When pressure arrives — economic, geopolitical, or popular — the regime snaps.

What makes the book relevant in 2025 is its discussion of modern autocracies like Russia, China, Turkey, and Iran. Dirsus cautions Western observers: authoritarian regimes appear strong right up until they break. The Soviet Union looked stable in 1989. Mubarak looked entrenched in 2010. The lesson is humility — and vigilance.

How Tyrants Fall is not triumphalist. It does not pretend that democracy automatically emerges after collapse. In fact, Dirsus is brutally honest: regime failure often produces chaos, not freedom. But his larger argument is that authoritarianism carries within it the seeds of its own destruction.

Mehvish Ali

Empire of AI

Karen Hao

2025

Artificial intelligence has created a new kind of empire — built not on land or armies, but on data, computers, corporate power, and algorithmic governance.

Karen Hao’s Empire of AI is one of the latest contributions to understanding the geopolitical implications of artificial intelligence. Unlike most AI books written by technologists or policymakers, Hao approaches the subject as a global investigative journalist.

Her central argument is that AI has already produced a new global empire — controlled not by nation-states but by a handful of corporations, research labs, and data monopolies. This empire governs through algorithmic systems that influence markets, politics, and even individual behaviour. Its power is diffuse but immense. And it is reshaping the world faster than regulators or democratic institutions can comprehend.

Hao argues that today’s AI boom mirrors historical imperial expansion: power is centralized in a few corporations and states, resources are extracted globally, and decisions with worldwide consequences are made without democratic accountability.

Using the rise of OpenAI as a central case study, she shows how ideals of openness and safety gave way to scale, secrecy, and geopolitical competition. The book highlights three pillars of this “AI empire”: concentrated corporate power, hidden labor in the Global South, and massive environmental costs.

One of the book’s most compelling ideas is that AI governance is increasingly geopolitical. Whoever controls the infrastructure — compute clusters, chip supply chains, talent pipelines, and training data — controls the future rules of global order. Hao exposes just how dependent governments are on private companies for critical natúional capabilities.

What makes the book really valuable is its nuance. Hao does not reduce AI to “good vs evil” narratives. She examines how AI improves crisis response, enables scientific breakthroughs, supports education, and empowers marginalised communities. Yet she insists that power must be acknowledged before benefits can be responsibly distributed.

Shabih Ul Hassan

How Progress Ends: Technology, Innovation, and the Fate of Nations

Carl Benedikt Frey

2025

Technological progress is not linear or inevitable — it has repeatedly stalled in history, and today’s world risks entering a period of innovation stagnation unless societies confront structural obstacles.

Technological progress is not linear or inevitable — it has repeatedly stalled in history, and today’s world risks entering a period of innovation stagnation unless societies confront structural obstacles.

Carl Benedikt Frey is best known for his research on automation and labour disruption. In How Progress Ends, he turns to a broader question: why do periods of rapid innovation end, and what determines whether societies continue advancing or fall into stagnation?

His central argument is that technological progress ends when social, political, and institutional structures fail to absorb and deploy new technologies. Innovation depends not only on scientific discovery but on the incentives, governance, and economic systems that allow ideas to scale.

Frey argues that we are entering a moment where progress may stall. Productivity growth is slowing. Regulatory environments are increasingly restrictive. Risk-taking is suppressed by cultural and demographic conservatism. And geopolitical fragmentation is reducing the global knowledge flows that fuel breakthroughs.

Using case studies from the Roman Empire to China, from Victorian Britain to the mid-20th-century United States, Frey demonstrates that societies often choose stagnation without realising it. Innovation is fragile. It requires openness, competition, and the willingness to disrupt existing elite interests.

In 2025, this argument feels timely. The world is simultaneously experiencing rapid breakthroughs (AI, biotech, materials science) and deep structural drag (ageing populations, declining entrepreneurship, regulatory overreach). Frey forces us to confront a provocative possibility: the technological frontier may be advancing, but society’s capacity to harness it may be retreating.

Adnan Khan

How to Hide an Empire

Daniel Immerwahr

2019

The United States built an empire — not through formal colonies, but through territories, military bases, and global infrastructure — and understanding this hidden empire explains modern geopolitics.

The United States built an empire — not through formal colonies, but through territories, military bases, and global infrastructure — and understanding this hidden empire explains modern geopolitics.

Daniel Immerwahr’s How to Hide an Empire is one of the most engaging histories of American power in decades. His central argument is that the United States is not the anti-colonial republic it imagines itself to be. It is an empire — a sprawling network of territories, protectorates, military bases, and logistical nodes that form the backbone of American global dominance.

Immerwahr’s brilliance lies in his storytelling. He resurrects forgotten histories of America’s island colonies, from Puerto Rico to Guam, the Philippines to the Marshall Islands. He shows how these territories were laboratories for US military strategy, chemical testing, and industrial policy. He also exposes the uncomfortable reality that America’s war-making capacity depends on a global “empire of bases.”

But his most fascinating argument is about the shift from territorial empire to technical empire. The US moved from ruling land to ruling systems — standards, technologies, supply chains, and finance. Immerwahr calls this the “pointillist empire,” where influence is exercised through strategic nodes rather than contiguous territory.

In a world where the US is now challenged by China’s Belt and Road, Russia’s security networks, and emerging multipolarity, Immerwahr’s book feels prescient. It forces readers to see power not as borders but as infrastructure.

This is essential reading for anyone trying to understand how the modern American-led order was built — and how it may unravel.

Mehvish Ali

Goliath’s Curse: The History and Future of Societal Collapse

Luke Kemp

2025

Civilisations collapse not from a single shock, but from the convergence of complexity, elite failure, ecological overshoot, and institutional rigidity — and today’s world exhibits all the classic patterns.

Civilisations collapse not from a single shock, but from the convergence of complexity, elite failure, ecological overshoot, and institutional rigidity — and today’s world exhibits all the classic patterns.

Goliath’s Curse blends sweeping historical narrative with sharp contemporary relevance. Its thesis is: societies do not fall because of a single cause — invasion, famine, war — but because their internal complexity becomes unmanageable, their elites become rigid or parasitic, and their ecological foundations erode. Collapse is the final stage of a system that can no longer adapt.

The author argues that modern civilisation mirrors many of the trajectories that doomed past empires. Not because history “repeats,” but because civilisations operate with similar constraints: resource limits, political fragmentation, bureaucratic sclerosis, and rising inequality. The book suggests that complexity — once a strength — becomes a liability when institutions ossify and elites fail to reform.

What sets Goliath’s Curse apart from typical collapse literature is its refusal to indulge in sensationalism. Instead, it examines the structural stresses that accumulate quietly: freshwater depletion, soil exhaustion, demographic inversion, global supply chain fragility, psychological alienation, and the polarisation that corrodes civic trust. Collapse becomes a process rather than an event — the result of societies losing the capacity to correct course.

The book’s most compelling chapters compare Rome’s late imperial sclerosis with the modern bureaucratic mega-state, and the environmental degradation that preceded Mayan and Khmer collapse with today’s planetary ecological overshoot. The author argues that technological sophistication does not protect societies; often it accelerates decline by allowing elites to postpone necessary reforms.

What resonates in 2026 is the author’s observation that collapse usually becomes visible only in hindsight. Civilisations rarely acknowledge when they have entered the downward phase. Instead, they double down on failed policies, expand repression, or try to revive past glory — the real signs that the system is breaking.

Goliath’s Curse is not fatalistic. It ends with the argument that societies can survive upheaval if they decentralise power, embrace adaptability, restore ecological balance, and rebuild civic cohesion.

Anam Sultan

The Once and Future World Order

Amitav Acharya

2025

The Western-led liberal international order is neither eternal nor unique — it is simply one iteration of many historically recurring world orders, and a new, more pluralistic order is now emerging.

The Western-led liberal international order is neither eternal nor unique — it is simply one iteration of many historically recurring world orders, and a new, more pluralistic order is now emerging.

Amitav Acharya is an expert on global orders, and The Once and Future World Order is his most ambitious book. His central argument challenges the West’s most cherished geopolitical myth: that the liberal world order is the natural, inevitable, or final stage of international politics. Acharya argues that world orders are historically contingent, culturally specific, and constantly evolving — and the Western-led system is now being replaced by a more decentralised, hybrid order.

His concept of a “multiplex world” is especially compelling. Instead of a single hegemonic centre of power, the world is evolving into a mosaic of regional systems — Asian, Middle Eastern, African, and Eurasian — each shaped by unique political cultures, power structures, and security dynamics. The United States remains important but no longer central. China is a major pole but not a replacement hegemon. Europe is a declining but still influential node. India, Turkey, Brazil, and the Gulf states are rising as autonomous actors.

Acharya’s historical chapters dismantle the myth of Western uniqueness by examining earlier multipolar systems — the Indian Ocean world, the Islamic Golden Age, the Chinese tributary order, and the pre-colonial African kingdoms. This historical breadth gives the book a refreshing depth, showing that the modern world is not entering uncharted territory but returning to a historically normal condition.

What makes the book powerful is its critique of Western strategic narratives. Acharya argues that the West misread the post–Cold War moment, believing the liberal order had triumphed permanently. Instead, globalisation empowered non-Western actors who are now shaping rules and norms in ways the West cannot control.

Acharya’s message is the world order is no longer about American leadership or Chinese dominance. It is about the diffusion of power, the diversification of global governance, and the erosion of any single model of modernity.

Kazi Ahmed

Land Power: Who Has It, Who Doesn’t, and How That Determines the Fate of Societies

Michael Albertus

2025

Control over land — its distribution, ownership structures, and political organisation — determines whether societies become stable, prosperous, or prone to conflict and authoritarianism.

Control over land — its distribution, ownership structures, and political organisation — determines whether societies become stable, prosperous, or prone to conflict and authoritarianism.

Michael Albertus’ Land Power is one of the most important political economy books in recent years, offering a simple but transformative argument: land — who owns it, who controls it, how it is distributed — shapes the long-term trajectory of societies more than ideology, institutions, or even culture.

Albertus challenges a common misconception: that land politics is a relic of the past, overshadowed by finance, technology, and globalisation. Instead, he shows that land remains the foundation of political power. In countries where land is concentrated among elites — from Latin America to the Middle East — political inequality becomes entrenched, democratic institutions weaken, and the state becomes captured by narrow interests.

The book’s historical range is impressive. Albertus traces land-based power from feudal Europe to colonial empires, from the Mexican Revolution to modern China’s urbanisation strategy. He argues that land reforms — when genuine — produce more stable political systems and broader economic development. But when elites manipulate land regimes, states become brittle, corrupt, and prone to authoritarian backsliding.

Albertus’ analysis is especially relevant for understanding today’s geopolitical hotspots. He argues that land inequality fuels insurgencies, civil wars, territorial grievances, and populist revolts. Whether in Colombia, Pakistan, India, or Ethiopia, land is often the silent root of political instability.

This is a masterpiece of political economy, and one of the most clarifying books for me.

Syed Fahad

Lobbying for Zionism on Both Sides of the Atlantic

Ilan Pappé

2024

Pro-Israel lobbying networks in the US and Europe have shaped political discourse, foreign policy, and public narratives far more deeply than acknowledged, often suppressing criticism of Israeli policy and entrenching geopolitical bias.

Pro-Israel lobbying networks in the US and Europe have shaped political discourse, foreign policy, and public narratives far more deeply than acknowledged, often suppressing criticism of Israeli policy and entrenching geopolitical bias.

Ilan Pappé has long been one of the most outspoken critics of Israeli state policy, and Lobbying for Zionism on Both Sides of the Atlantic is his most direct confrontation with the political lobbying infrastructure behind it. The book’s central argument is that pro-Israel lobbying networks in Washington, London, Brussels, and European capitals have created a political environment where meaningful critique of Israeli policy becomes institutionally suppressed.

Pappé meticulously documents how think tanks, political action committees, media networks, and philanthropic donors shape public discourse. But what makes the book compelling is not the exposé itself — much of this influence is known — but Pappé’s argument that lobbying succeeded because it tapped into deeper Western cultural assumptions. Zionism aligned with Western narratives of civilisation, security, and guilt, making it unusually effective.

The book does not claim a conspiracy; instead, Pappé shows that these networks operate like any other powerful lobbying ecosystem — except far larger, more coordinated, and more institutionalised. He argues that this influence has constrained Western foreign policy options, marginalised Palestinian voices, and distorted the public’s understanding of the conflict.

In the context of the Gaza war and shifting global attitudes, Pappé’s argument feels timely. He suggests that Western societies are experiencing a slow realisation that their political discourse has been structurally shaped by decades of lobbying — and that this realisation is generating political backlash, especially among younger voters.

Whether one agrees with Pappé or not, this book forces a confrontation with the uncomfortable question of how influence is manufactured in western societies.

Mortaza Akbar

Tower of Basel: The Shadowy History of the Secret Bank that Runs the World

Adam LeBor

2013

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) is one of the most powerful and least accountable institutions in the world — a technocratic hub shaping global finance from behind the scenes.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) is one of the most powerful and least accountable institutions in the world — a technocratic hub shaping global finance from behind the scenes.

Adam LeBor’s Tower of Basel is a history of one of the most mysterious institutions in international finance: the Bank for International Settlements. Created in 1930, it has survived world wars, financial crises, and the evolution of the global monetary system — all while maintaining an extraordinary level of secrecy.

LeBor argues that the BIS operates as a technocratic empire. It sets the rules for global banking standards, coordinates financial policy among central banks, and influences crises from the shadows. The central argument is that the modern financial order is not governed by elected officials, but by an elite network of central bankers and technocrats who operate beyond democratic oversight.

What makes the book gripping is its historical narrative. LeBor uncovers the BIS’s role in laundering Nazi gold, coordinating the postwar financial order, and managing the transitions from Bretton Woods to the modern dollarised system. He shows how crises like 2008 revealed the true power of the BIS — it acted as the command centre for stabilising the global banking system.

The book is not conspiratorial; it is analytical. LeBor does not claim that the BIS “runs the world,” but that it exemplifies how technocratic institutions wield enormous authority in shaping the global economy. The BIS is powerful precisely because it is unelected, insulated, and designed to be invisible.

Adnan Khan

107 Days

Kamala Harris

2025

The first 107 days of a presidency reveal not just political priorities but the character of leadership itself — and Harris frames her short tenure as democratic presidential nominee as a fight to reclaim stability, dignity, and democratic resilience amidst national turmoil.

The first 107 days of a presidency reveal not just political priorities but the character of leadership itself — and Harris frames her short tenure as democratic presidential nominee as a fight to reclaim stability, dignity, and democratic resilience amidst national turmoil.

107 Days is a political memoir by Kamala Harris, the 49th vice president of the United States, in collaboration with author Geraldine Brooks.The book details Harris’s 2024 presidential campaign spanning from Joe Biden’s withdrawal from the election on July 21, 2024, to Election Day on November 5, with the title referencing the length of her campaign

Kamala Harris recounts the chaotic, emotionally charged period of her election campaign for US president — the crises she inherited, the pressures she endured, and the fierce attempts to stabilise a nation fraying under institutional distrust and polarisation.

Her central argument is that leadership is forged under pressure, and that the health of a democracy depends on a leader’s ability to restore credibility after periods of institutional shock. Harris frames her tenure as a struggle against disinformation, political violence, racial tension, and executive overreach. She believed her campaign represented an attempt to stop a downward spiral in American governance.

The book’s strongest chapters are the ones where Harris steps away from rhetoric and discusses the mechanics of wielding power: negotiating with Congress, confronting security briefings about domestic extremism, managing a White House still psychologically scarred by the previous administration, and facing an American public exhausted by crisis. Harris writes candidly about moments of doubt and the crushing emotional weight of governing a divided country.

At times the book is self-justifying, it belongs to a genre — the presidential memoir written from the inside of a storm — where the author must defend decisions that history will judge. Harris does this with characteristic framing: the struggle is not merely political, but civilisational. She argues that democracies do not collapse in dramatic moments, but through accumulated distrust, institutional sabotage, and a public that gives up on the idea of a common nation.

What the book confirms is that Harris did not learn the failure over Gaza in those 107 fateful days. Israel’s genocide was perpetrated with weapons and political cover supplied in large part by the Biden administration. But for such a defining, gruesome issue, Harris shows no introspection or awareness. The former presidential candidate sticks to the script in this memoir.

Shabih Ul Hasan

The Man Who Would Be King: Mohammed bin Salman and the Transformation of Saudi Arabia

Karen Elliott House

2025

Mohammed bin Salman’s rise is reshaping the Middle East — not through gradual reform but through an unprecedented consolidation of personal power, economic ambition, and authoritarian modernisation.

Mohammed bin Salman’s rise is reshaping the Middle East — not through gradual reform but through an unprecedented consolidation of personal power, economic ambition, and authoritarian modernisation.

Karen Elliott House offers one of the most consequential portraits of a contemporary leader in The Man Who Would Be King. Her central argument is that Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) is transforming Saudi Arabia through a model she calls “authoritarian modernisation” — sweeping economic and social reforms enforced through absolute political control.

House, who has covered Saudi Arabia for decades, writes with the clarity of someone who has watched the kingdom evolve from a theocracy to ambitious regional power. She describes MbS as a paradox: a visionary moderniser and an uncompromising autocrat, a leader who dismantles old taboos while constructing a new political order centred entirely around himself.

The book highlights the magnitude of MbS’s economic project. Vision 2030 is not a development plan — it is an attempt to rewrite the entire social contract. House details how MbS aims to shift the kingdom away from oil dependence, open the economy to foreign capital, and create new industrial pillars in tourism, logistics, entertainment, and defence. She argues that no leader in the modern Middle East has attempted economic transformation at this scale and speed.

But House also notes the coercive foundations of MbS’s rule. The Ritz-Carlton purges, the centralisation of security services, the suppression of clerical opposition, and the sidelining of rival princes show that his modernisation project is inseparable from authoritarian consolidation.

What makes the book powerful is House’s analysis of MbS’s geopolitical strategy. The crown prince sees Saudi Arabia as the indispensable Arab power — able to shape oil markets, balance Iran, and partner with China, India, and the United States on its own terms. House argues that MbS is positioning Saudi Arabia for a post-American Middle East, even as he maintains a pragmatic relationship with Washington.

Mozimmal Hussain

The Thinking Machine: Jensen Huang, Nvidia, and the World’s Most Coveted Microchip

Stephen Witt

2025

Nvidia’s rise under Jensen Huang illustrates how modern geopolitics has shifted from territorial conflict to competition over semiconductors — and how one company built the hardware infrastructure driving the AI revolution.

Nvidia’s rise under Jensen Huang illustrates how modern geopolitics has shifted from territorial conflict to competition over semiconductors — and how one company built the hardware infrastructure driving the AI revolution.

Stephen Witt’s The Thinking Machine is a riveting study of ambition, engineering genius, and geopolitical consequence. The central thesis is that Nvidia — and its founder, Jensen Huang — sit at the centre of the 21st century’s most important technological transformation: the global race for artificial intelligence.

Witt frames Huang as an unlikely empire-builder: a Taiwanese immigrant who built a company not by dominating consumer markets but by mastering a niche — graphics chips — that evolved into the backbone of machine learning. The book chronicles Nvidia’s evolution from a gaming hardware firm into the world’s most strategically important semiconductor company, producing chips that governments, corporations, and militaries now treat as national security assets.

The book’s power lies in its explanation of why GPUs matter. Witt shows how Nvidia’s parallel processing architecture — initially designed for graphics rendering — became perfect for training neural networks. Huang recognised this earlier than anyone else and built an ecosystem (CUDA, software tools, developer communities) that locked in Nvidia’s dominance.

Witt’s geopolitical chapters are superb. He traces how Nvidia became entangled in US-China competition, with Washington imposing export controls and Beijing racing to develop domestic alternatives. He shows how cloud giants — Amazon, Google, Microsoft — depend on Nvidia’s chips to power their AI models, giving Huang extraordinary leverage over the most powerful corporations in the world.

What emerges is a portrait of a man who is half-engineer, half-strategist. Huang built not just a chipmaker, but the computational backbone of modern AI. In a world where semiconductors is the new oil, Nvidia is the new OPEC — except it is run by one man.

The Thinking Machine tries to explain the future by telling the story of the man who built its engine.

Sufyan Badar

War and Power: Who Wins Wars — and Why

Phillips Payson O’Brien

2025

Victory in war is determined not by battlefield heroics but by industrial capacity, logistics, and the ability to sustain long-term mobilisation — and modern great-power competition is once again shaped by these fundamentals.

Victory in war is determined not by battlefield heroics but by industrial capacity, logistics, and the ability to sustain long-term mobilisation — and modern great-power competition is once again shaped by these fundamentals.

Phillips Payson O’Brien has spent years challenging popular myths about warfare. In War and Power, he presents a clear, forceful thesis: wars are not won by tactical brilliance or elite units, but by the ability to build, supply, and maintain overwhelming military capacity. Logistics, production, and economic resilience determine victory — not strategy alone.

O’Brien’s argument runs counter to the romanticism that dominates much military literature. He dismantles the myth of decisive battles, showing instead that modern warfare is shaped by attrition, supply chains, and industrial output. Using World War II as his foundational case study, he shows how the Allies’ victory stemmed from manufacturing superiority rather than battlefield genius.

The book then turns to the modern era. O’Brien argues that the same dynamics shape contemporary conflicts. Russia’s war in Ukraine, China’s military rise, and US power projection all hinge on industrial capabilities — semiconductor supply chains, artillery shell production, logistics fleets, and the ability to scale advanced weapons systems.

One of the book’s most striking insights is that great-power conflict has moved beyond mere material output. Today, victory hinges on the ability to mobilise complex production ecosystems — integrating AI, advanced materials, precision manufacturing, and globalised supply chains. O’Brien argues that the US still leads, but China is closing the gap rapidly, while Europe has fallen dangerously behind.

War and Power is a deeply clarifying book. In an era of high-tech warfare, it reminds us that fundamentals still matter — factories, energy grids, transport networks, and the political will to mobilise them. O’Brien argues that states preparing for future conflict must rediscover the industrial mindset they abandoned after the Cold War.

Mortaza Akbar

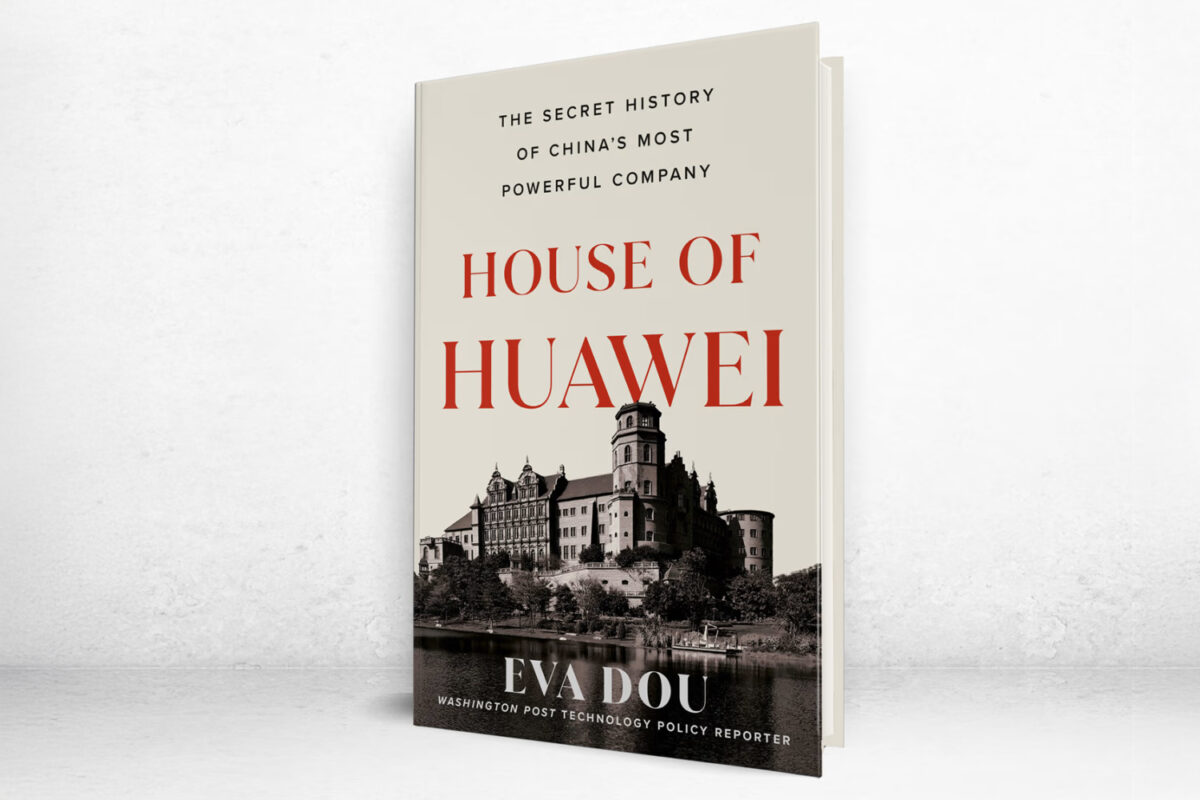

House of Huawei: The Secret History of China’s Most Powerful Company

Eva Dou

2025

Huawei’s rise is not merely a corporate success story but a window into the evolution of China’s state–tech ecosystem — a model where innovation, security, and national power fuse into a single strategic project.

Huawei’s rise is not merely a corporate success story but a window into the evolution of China’s state–tech ecosystem — a model where innovation, security, and national power fuse into a single strategic project.

Eva Dou’s House of Huawei is the most comprehensive and revealing account yet written on the company that has become both a symbol and instrument of China’s technological ascent. It’s not a polemic and not a Western security brief disguised as a book; instead, Dou traces Huawei’s growth through Chinese business culture and its political undercurrents. The central argument she develops is that Huawei embodies the new Chinese developmental model — a hybrid of private ambition, state support, ideological loyalty, and national mission.

Dou begins by demystifying Ren Zhengfei. He is neither the mythic Confucian patriarch portrayed in Chinese media nor the shadowy PLA operative imagined by Western intelligence agencies. Instead, he emerges as a man shaped by deprivation, discipline, and the brutal competitiveness of China’s early reform era. Dou shows how Ren built Huawei through sheer organisational rigor, a near-fanatical work culture, and a willingness to enter markets Western firms ignored.

The book shines most in its exploration of Huawei’s internal culture. “Wolf culture,” the company’s famed ethos, was not a slogan but a survival mechanism. Employees worked extreme hours, took enormous risks, and viewed foreign competitors — especially American ones — as existential threats. Dou explains how this culture, blended with Chinese Communist Party organisational norms, created a company that could scale faster than any Western rival.

Dou shows how Huawei became central to China’s national strategy: securing telecommunications infrastructure, expanding digital influence across Africa and the Middle East, and challenging American dominance in network technology. She demonstrates that Huawei was welcomed by global markets for its cost and quality, but targeted by Western governments fearful of strategic dependency.

Some of the most powerful chapters examine the 5G wars. Dou illustrates how the US ban was not about Huawei’s misdeeds alone, but about a deeper panic: Western recognition that it had sleepwalked into a world where China was the technological pace-setter.

Dou also details Huawei’s missteps: opaque governance, entanglement with state security organs, and a failure to understand global political risk. She suggests that Huawei’s crisis is also China’s crisis — a nation whose technological ambitions collided with the realities of geopolitics.

Huawei is neither villain nor hero. It is a mirror of China’s transformation: ambitious, disciplined, opaque, and increasingly constrained by geopolitical rivalry. For anyone trying to understand the technological foundations of the coming multipolar order, this is indispensable reading.

See full review

Adnan Khan

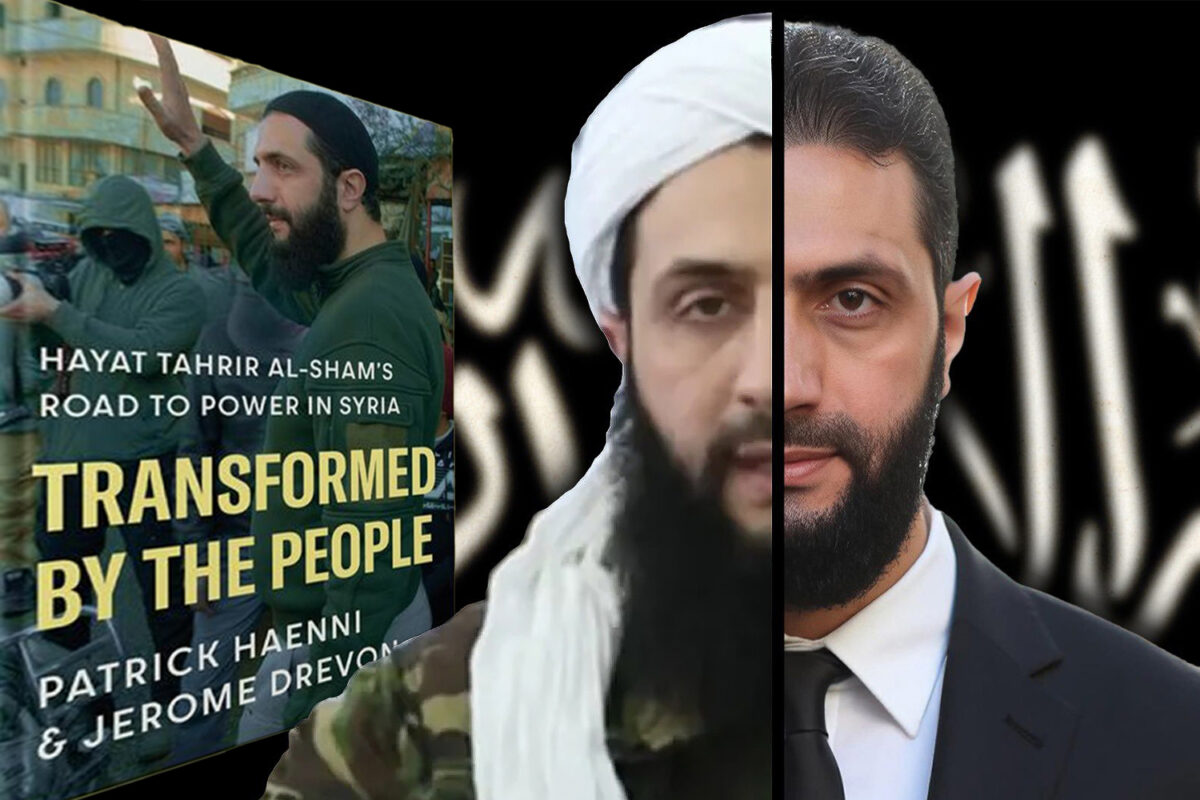

Transformed by the People: Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’s Road to Power in Syria

Patrick Haenni & Jérôme Drevon

2025

HTS’s evolution from jihadist insurgency to proto-governing authority reveals how militant movements adapt under pressure — and how ideology bends to the realities of governance, survival, and legitimacy.

HTS’s evolution from jihadist insurgency to proto-governing authority reveals how militant movements adapt under pressure — and how ideology bends to the realities of governance, survival, and legitimacy.

Transformed by the People is the first book on the new leader of Syria, which looks at Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) not as a static terrorist organisation, but as a political actor undergoing profound internal transformation. Patrick Haenni and Jérôme Drevon bring years of field research and direct access to HTS figures, producing a study of this granular and analytical book. .

The central argument is that HTS’s transformation was not a top-down ideological shift, but a bottom-up process driven by social pressures, battlefield realities, and the need to govern territory. In other words: the Syrian conflict forced HTS to evolve from jihadists into administrators, police officers, tax collectors, and pragmatic power brokers.

Haenni and Drevon demonstrate that this transformation was not linear. HTS was born from the ashes of al-Nusra Front, itself an al-Qaeda affiliate. Its leadership, including Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, initially positioned themselves as the purist vanguard of global jihad. But the authors show, in painstaking detail, how HTS gradually decoupled from al-Qaeda, sidelined foreign fighters, and embraced an agenda rooted in local governance rather than global jihad.

The book portrays Jolani as a pragmatic — even Machiavellian — political entrepreneur. He understood that survival required legitimacy, and legitimacy required governance. He saw that the Syrian population in Idlib wanted security, bread, and order more than ideology. And he positioned HTS accordingly.

This evolution is uncomfortable for analysts who prefer clean categories: terrorist groups act like terrorists; rebels act like rebels. Haenni and Drevon show that in reality, armed groups evolve when forced to shoulder the burdens of statehood. HTS built courts, regulated markets, rebuilt infrastructure, and created a bureaucratic architecture resembling a quasi-state. Its ideology adapted accordingly — not abandoned, but reframed.

The authors are clear-eyed about HTS’s abuses: repression of rivals, manipulation of aid agencies, and deep entanglement in covert regional politics. But they challenge the assumption that HTS’s transformation is superficial. Their interviews suggest that the group’s leadership genuinely recalibrated their worldview, redefining jihad not as global revolution but as local governance rooted in Islamic legitimacy.

Transformed by the People is an academic study rather than a political study of one of the most famous non-state actors .

See full review

Adnan Khan

Original Sin: President Biden’s Decline, Its Cover-Up, and His Disastrous Choice to Run Again

Jake Tapper & Alex Thompson

2025

Biden’s decision to run for a second term — despite clear cognitive decline — exposed the structural weaknesses of the American political system, where party loyalty, institutional inertia, and elite self-preservation override public interest.

Biden’s decision to run for a second term — despite clear cognitive decline — exposed the structural weaknesses of the American political system, where party loyalty, institutional inertia, and elite self-preservation override public interest.

Original Sin is one of the most controversial political books of the year, not because it is sensationalist, but because it touches a nerve at the centre of American politics: the inability of the system to confront presidential weakness. Jake Tapper and Alex Thompson have written a meticulously sourced, deeply reported account of the months — and years — during which Biden’s physical and cognitive decline became an open secret in Washington.

The central argument is not about Biden the man, but about the system around him. Tapper and Thompson argue that the Democratic Party, the White House inner circle, the media ecosystem, and institutional actors all colluded — sometimes consciously, sometimes through inertia — to hide Biden’s deterioration from the public. Not out of malice, but from fear: fear of losing power, fear of handing victory to Trump, fear of confronting the absence of viable successors.

The book paints Biden with sympathy. He is portrayed as a man who spent a lifetime chasing the presidency and could not let go. But it does not spare the people around him: aides who protected him from unscripted interactions; party leaders who dismissed internal warnings; donors who prioritised stability over transparency. The book documents moments that, in retrospect, signalled decline: lapses during briefings, difficulty with names, confusion during meetings.

What makes Original Sin powerful is how it captures the psychology of denial in politics. Institutions do not confront uncomfortable truths until forced to. Instead, they construct incentives around maintaining the illusion of normalcy. Tapper and Thompson detail how staffers built increasingly rigid protective layers around Biden, limiting access, controlling information flows, and preventing internal dissent.

This system functioned — until it collapsed. The book’s later chapters show how crises, debates, foreign policy briefings, and unexpected public moments tore through the carefully curated façade. The authors argue that by insisting Biden was capable of serving another term, Democrats exposed the fragility of their own coalition and undermined public trust at a critical moment.

But the book’s deeper insight is that this was not just a Democratic failure — it was an American one. The US presidency remains a role that demands performance, perception, and symbolic strength. Biden’s decline revealed how ill-equipped the political system is to manage succession, acknowledge mortality, or confront the limits of its leaders.

Original Sin reflects a deeper political dysfunction: a system that cannot tell the truth about its highest office without triggering crisis. It is not just a story about one man’s decline; it is a story about a country’s.

See our full review

Adnan Khan

Our Dollar, Your Problem

Kenneth Rogoff

2025

What happens to the world when the cornerstone of global finance – the U.S. dollar is no longer unchallenged?

In a year when debates over global financial stability, debt crises, and shifting geopolitical alliances are intensifying, Rogoff’s book offers timely insight into the backbone of the world economy: the dollar. As nations reassess reserve currencies and emerging powers push alternatives, this book is essential for policymakers, economists, investors, and anyone tracking the future of global power and economic order.

Rogoff’s central thesis is that the dollar’s long-standing dominance is no guarantee of permanence and argues that mounting US debt, political instability, rising interest rates, and growing efforts to diversify away from the dollar pose real challenges to its primacy. While no single currency is poised to replace it outright, a more fragmented, multipolar monetary world may be emerging, one with profound geopolitical implications.

Some readers find the book’s mainstream economic framing limited, arguing that it focuses on financial mechanics and US policy choices without fully engaging deeper structural critiques of global monetary power or geopolitical asymmetries.

Our Dollar, Your Problem is a clear, accessible, and broadly informed analysis of one of the most consequential issues in global affairs today. Rogoff makes a strong case that the dollar’s future is not assured and that its evolution will shape geopolitics in the decades ahead. Its insights are indispensable for understanding how financial power underpins the international order in 2025 and beyond.

Shabih Ul Hasan

Iran’s Grand Strategy: A Political History

Vali Nasr

2025

What if Iran’s foreign policy isn’t driven by Islamic zeal or blind hostility to US Imperialism, but by a long-standing, calculated strategy shaped by history, vulnerability, and the quest for security.

What if Iran’s foreign policy isn’t driven by Islamic zeal or blind hostility to US Imperialism, but by a long-standing, calculated strategy shaped by history, vulnerability, and the quest for security.

In a year marked by the Gaza genocide, shifting Middle East dynamics, renewed nuclear negotiations, and ongoing tensions between Iran, the US and regional powers, this book offers essential context for anyone seeking to understand Tehran’s choices, and misperceptions of them. Nasr dispels simplistic narratives and situates Iran within the broader currents of national strategy and geopolitical competition.

Nasr’s central argument is that Iran’s grand strategy is rooted not in ideological export or theological fervor, but in a pragmatic, historical quest for independence, survival, and regional influence within the US led order in the Middle East. He traces how the trauma of the 1979 revolution and the defining Iran-Iraq War forged a strategic culture of resistance and self-reliance that continues to shape Tehran’s foreign policy, nuclear posture, and regional alliances. According to Nasr, concepts like “sacred defense” and “forward defense” are less abstract slogans and more enduring strategic tools designed to preserve sovereignty and counter perceived US dominance, while also pragmatic enough to align itself with hostile Western powers to achieve its objectives.

Iran’s Grand Strategy is a timely, nuanced, and richly researched contribution to Middle East geopolitics. Nasr goes beyond stereotypes to reveal the structural logic behind Iran’s actions and dilemmas, making this book an invaluable resource for anyone trying to understand the motives and limits of Iranian statecraft today.

Shabih Ul Hasan

New Power: Why outsiders are winning, institutions are failing, and how the rest of us can keep up in the age of mass participation

Jeremy Heimans & Henry Timms

2018

What if the way power works in the world has shifted from closed, hierarchical systems to open, participatory networks, and that shift is remaking politics, business, and society.

What if the way power works in the world has shifted from closed, hierarchical systems to open, participatory networks, and that shift is remaking politics, business, and society.

In 2025, geopolitics is shaped not just by state actors but by movements, platforms, and networks that mobilize millions at lightning speed. New Power offers a lens for understanding how digital participation, social movements, and decentralized influence are reshaping authority and legitimacy globally. This book is valuable for activists, political movements, and anyone aiming to grasp how power dynamics are evolving in the digital age.

Heimans and Timms argue that we are living through a fundamental transformation in how power is exercised. They distinguish “old power”, centralized, guarded, and top-down, from “new power”, which is participatory, peer-driven, and networked.

While old power is like a currency held by a few, new power flows like a current, gaining force through mass participation and remixing. Through examples ranging from social movements and political campaigns to brands and cultural phenomena, the authors show how new power enables outsiders to challenge institutions and why traditional authorities struggle to adapt.

New Power is a timely and accessible exploration of how networked participation is transforming influence in the 21st century. While not without its limits, the books depth of analysis provides a useful framework for readers trying to make sense of movements from viral activism to decentralized political influence.

Shabih Ul Hasan