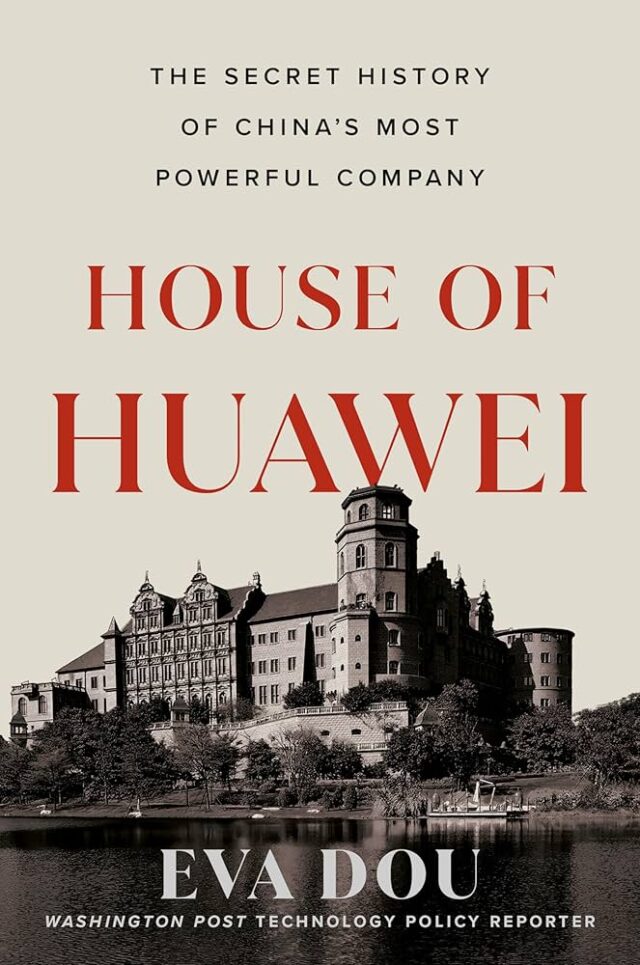

House of Huawei: The Secret History of China’s Most Powerful Company

Eva Dou

2025

Huawei is currently China’s most successful company that many in the West have ever heard of. The enormous company is one of the world’s biggest producers of behind-the-scenes equipment that enables fibre broadband, 4G and 5G phone networks. Its hardware is inside communications systems across the world.

Huawei is currently China’s most successful company that many in the West have ever heard of. The enormous company is one of the world’s biggest producers of behind-the-scenes equipment that enables fibre broadband, 4G and 5G phone networks. Its hardware is inside communications systems across the world.

That is what prompted alarm from US lawmakers, who accused Huawei of acting as an agent for China’s government and using its technology for espionage. The company insists it merely complies with the local laws wherever it operates, just like its US rivals. Nevertheless, its equipment has been ripped out of infrastructure in the UK at the behest of the government, its execs and staffers have been arrested across the world. Most famously, in 2018, Meng Wanzhou, Huawei’s chief financial officer and daughter of Huawei founder, Ren Zhengfei, was arrested in Canada at the behest of US authorities.

Eva Dou, in her book chronicles the history of Huawei since its inception, its growth and the global challenges it has faced, as well as the lives of founder Ren Zhengfei and his family.

Founded in Shenzhen as a collectively owned enterprise in 1987, Huawei now operates in over 170 countries and rakes in annual revenues close to $100 billion. In Dou’s telling, much of the company’s success derives from its founder, Ren Zhengfei, an innovative, fiercely competitive, and fearless entrepreneur who occasionally skirted the law—and perhaps even broke it. Also crucial to the company’s growth was the mutual dependence it developed with the Chinese Communist Party. As Dou documents, the CCP provided the firm with capital and market opportunities at critical junctures, and Ren openly aligned the company with the party’s political priorities. By 2007, almost 20 percent of Huawei’s employees were CCP members—roughly three times the percentage of CCP members in China’s population.

Dou’s central argument is that Huawei’s meteoric rise is not merely a business success story, but a profound challenge to long-held Western beliefs about free markets, democracy, and the sources of innovation. The book frames Huawei’s emergence as China’s Sputnik moment, akin to the Soviet Union’s space triumph in 1957, which forced a reconsideration of communist methods versus western liberal democracy. Huawei, as the world leader in 5G, smartphones, and patent applications, and with annual sales surpassing Disney and Nike combined, defies the western notion that such a corporate juggernaut could not emerge from a communist system.

House of Huawei provides several key insights into China’s broader technological development through the lens of Huawei’s journey. China’s government actively fostered domestic tech champions to achieve self-sufficiency. This is exemplified by the military engineer Wu Jiangxing’s “04 switch” in 1991, China’s first homegrown advanced digital telephone switch, which galvanized Huawei’s own R&D efforts.

Huawei, much like China’s broader tech rise, initially relied on copying existing technology, as admitted by Ren Zhengfei regarding the BH-03 switch, stating “Our imitation was also legalized” after the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications ordered Zhuhai Telecom to license its technology. However, the company rapidly invested in R&D, exemplified by its HiSilicon chip unit and its lead in 5G polar coding technology, moving from being a follower to a leader in technological advancements.

Dou highlights Huawei didn’t just grow organically; it strategically used China’s diplomatic overtures to open new markets. For instance, following the strategic partnership between China and Russia in 1996, Ren Zhengfei attended an international convention in Moscow, explicitly stating that Huawei was “…benefiting from the influence of both General Secretary Jiang and President Yeltsin” to establish its Russian office. This pattern extended to operations in countries like Iraq, Iran, and North Korea, where Huawei was willing to go where Western companies shied away due to sanctions or political instability, thus gaining crucial early market share and experience.

Huawei’s global expansion directly contributed to the decline of established Western telecom giants. After Huawei secured the BT contract in 2005, Western rivals like Britain’s Marconi and Canada’s Nortel considered Huawei takeovers, with Nortel ultimately going bankrupt in 2009, driven out of business in part by its inability to match Huawei’s low prices. This shift in market power provoked strong reactions from Western governments, leading to initiatives like the Clean Network, which aimed to exclude Huawei from global telecom networks, directly framing the competition in geopolitical terms.

Eva Dou draws from extensive interviews and documents and avoids polemics while capturing the story’s geopolitical weight. She interweaves human drama, corporate strategy, and Chinese history. Dou demonstrates that China’s tech rise, as personified by Huawei, is a meticulously engineered national endeavor that blends market principles with state objectives, challenging the global technological and geopolitical order. Huawei’s journey from a small switchmaker to a global titan is presented as a microcosm of China’s broader ambition to become a leading world power, willing to endure significant challenges to achieve its strategic goals.

House of Huawei offers a detailed narrative of Huawei’s trajectory, which in turn reveals profound insights into China’s broader technological development and its rise as a global power. The book positions Huawei as a crucial lens through which to understand China’s unique approach to innovation, economic growth, and geopolitical influence, challenging conventional western assumptions about market economies and democracy.

House of Huawei succeeds as an urgent primer on China’s tech-politics fusion. It exposes how a single company can symbolise a nation’s ambitions, fears, and contradictions. Dou’s work invites reflection on the trajectory of global tech power structures—especially as digital infrastructure becomes geopolitically charged.