The world’s population reached 8 billion people on Tuesday, 15th November 2022, and will hit 9 billion in 15 years as it experiences an unprecedented surge in the number of older people, according to the latest UN data. All the research in the last few decades accepted that the world was facing a severe population explosion. Uncontrolled population growth would outstrip scarce resources and devastate the environment. More people would require more resources in the form of food and energy, which in turn would lead to a rise in global warming and other ecological catastrophes. But in the 21st century all over the world, countries are confronting population stagnation and declining fertility rates. Maternity wards are already shutting down in Italy. Ghost cities are appearing in China. Universities in South Korea can’t find enough students, and in Germany, hundreds of thousands of properties have been razed, with the land turned into parks.

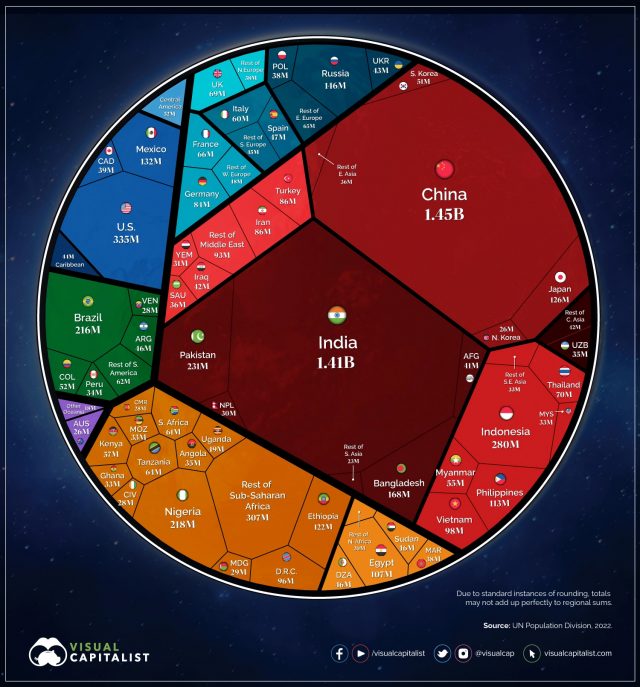

It took the whole of recorded human history until 1804 to reach 1 billion people. The next billion was added in under 125 years. The next billion was added to the world’s population in just three decades by 1960. In the next 40 years to the eve of the 21st century the global population doubled from 3 billion to 6 billion people. 71 million people were added annually between this period. Not only did the population of the world grow, but the growth rate accelerated exponentially. A lot of this population growth was driven by just 30% of the global population in places such as sub-Saharan Africa, Nigeria and South Asia. However in half of the world’s population, the era of high fertility has already ended.

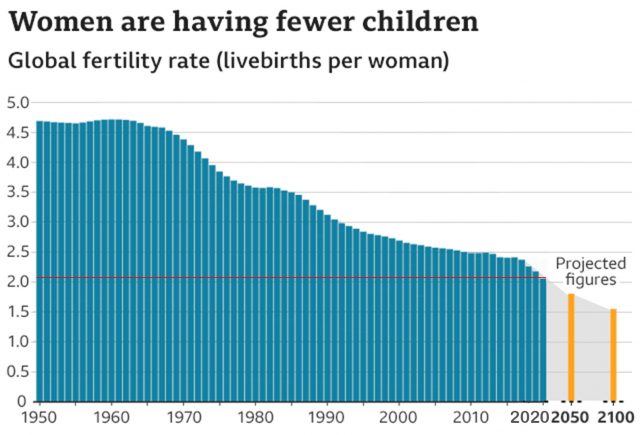

In the 21st century, growth rates are not accelerating but falling. According to the UN, between 2000 and 2050 the population will continue to grow, but only by about 50%, halving the growth rate of the previous fifty years. In the second half of the century, growth rates are anything between 0-10%. The annual increase in world population is expected to be 57 million a year on average between 2000 and 2050. This is smaller than the 71 million people added annually between 1950 and 2000. At some point in the 21st century the colossal growth rates seen in the global population will cease to exist. We already see change taking place in the developed nations. The declining birth rates have led to fewer younger workers to support the large increase in pensioners. Europe and Japan are experiencing this problem already. Many also assumed population growth might be slowing down in Europe, but the world’s total population will continue to grow because of high birth rates in the third world. But birth rates are plunging everywhere. The first world nations are on the bitter edge of decline, but the rest of the world is following right behind them. And this demographic shift will help shape the remainder of the 21st century.

The critical number for fertility is 2.1 births per woman. This is the number of children that each woman must have, on average, in order to maintain a generally stable world population. Anything above that number and the population grows; anything below, the population declines. According to the UN, women had an average of 4.5 children in 1970. In 2000, that number had dropped to 2.7 children. This is a dramatic drop. The UN forecasts that in 2050, the global fertility rate will decline to an average of 2.05 births per woman. That is just below the 2.1 needed for a stable world population. The UN has another forecast, based on different assumptions, where the rate is 1.6 babies per woman. So the UN, which has the best data available, is predicting that by the year 2050, population growth will be either stable or declining dramatically.

Before the advent of industrialization wealth to a large extent depended upon the number of children there were in a family. The more children the more workers or the more people that could work in the fields. This changed with the advent of factories that could use machines to churn out more goods than a labour worker could. The last two hundred years has seen more technological and scientific development than the whole of human history put together. Infants are no longer dying in large numbers before they reach the age of eight. Many illnesses that led to early deaths have been vaccinated against and as a result the world population grew at a colossal rate. The industrial and service needs of the global economy as well as more consumers to act as the lubricant for the global economy has seen the redefinition of the family unit, women and sexuality. The needs of the global economy, the need for consumers has led to the transformation of women and thus the family structure. Women no longer see their role as in the house to bear children but now as independent women who can pursue careers at the expense of having children and play a major role economically. The values of family and children have been replaced by individualism and a women’s economic value. Equality, feminism and LGBT have in many ways been the concepts that have been the death nail for the traditional family structure. The woman being the child bearer, house maker and the husband being the breadwinner has been completely transformed today and this is reflected in the fall in fertility rates around the world.

Whilst growth rates are dropping across the world, in the Muslim world fertility rates have reduced over the past decades, but remain well above the replacement rate and this is why the Muslim world, from Indonesia to Morocco will continue to grow for the remainder of the 21st century. Muslims have more children than members of the other major religious groups. Each Muslim woman has an average of 3.1 children, significantly above the next-highest group (Christians at 2.7) and the average of all non-Muslims (2.3).

After a century of explosive growth fertility rates have slowed and are projected to slow further from 2020. The population in the Muslim world until 2050 is only going in one direction and this is up, although the rate of growth is expected to slow. Going forward, there are few places in the world that will be subject to as much pressure from growing numbers of people as the Muslim world. This rising population will need to be watered, housed; they will need new and modern transportation systems and labour markets. Competition for jobs, especially government jobs, and housing and the poor quality and inadequate provision of public services are prime causes of the deep dissatisfaction with the status quo that marks so many of these societies. The stress these demographic pressures exert – and regional governments’ ability to mitigate them – will play a major role in determining the future trajectory of the Muslim world.

After decades of shouting wolf with overpopulation the world is in reality heading towards a demographic crunch. In a few decades we will be speaking about the lack of people, the lack of youth and the increase in pensioners. This will have serious implications for geopolitics, global power and economics.

For further reading see our Deep Dive on: The Geopolitics of Population