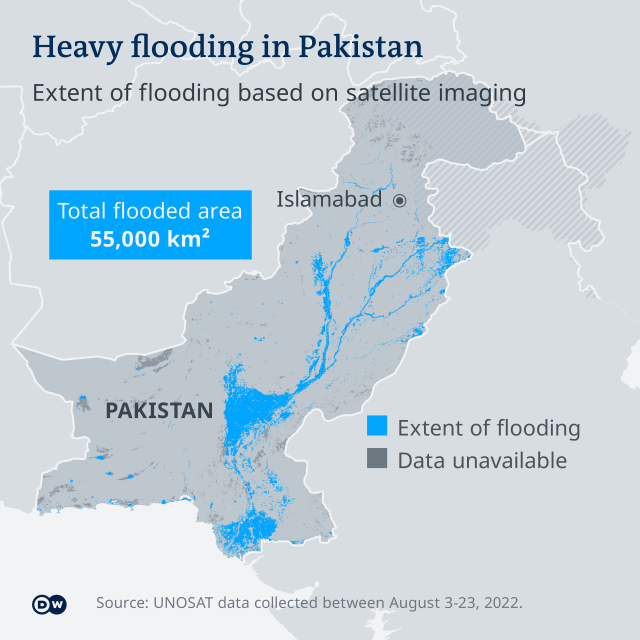

Bahadur Khan an Afghan refugee in Pakistan’s northern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa described the floods inundating Pakistan as something he will never forget as his house was under water in minutes. Bahadur and his family had weathered the torrential downpours of Pakistan’s annual monsoon since its onset in June, but he was not prepared for the dramatic surging of the Kabul River on the 2nd September. The waters broke through a nearby embankment in the early hours of the morning and he had only 10 minutes to evacuate his loved ones to the safety of higher ground before his home was swept away. It was the third time the 60-year-old grandfather has been uprooted in his life. Pakistan is grappling with its worst flooding in living memory. A staggering one-third of the country is underwater – more than the whole of the UK. More than 30 million people have been affected and at least 2,000 people have perished. This is not the first time Pakistan has suffered from flooding’s and this has led to many in Pakistan to condemn the government for failing to prepare for such disasters.

Pakistan has a long history of floods and heavy rains. Since independence in 1947 Pakistan has been flooded 68 times. The monsoon season comes around June every year, but this year temperatures reached world record levels throughout the region. These temperatures led to the sea temperature to increase which in turn increased the monsoon rainfall. The heavy downpours affected India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal and Afghanistan, but Pakistan has been battered by the monsoon rains that has affected over half the country. Pakistan received almost twice its average annual rainfall already in 2022. Whilst Sindh and Balochistan received more than five times that average. When Pakistan see’s such a deluge of rain, once on land, much of that water has nowhere to go. This would explain why more than 1.2 million houses, 5,000 kilometres of road and 240 bridges have been destroyed.

Pakistan has a long history of floods and heavy rains. Since independence in 1947 Pakistan has been flooded 68 times

Climate Change Minister Sherry Rehman has been leading the Pakistan government’s response and renewed the government’s appeal for international assistance, while also blaming major industrialised countries for their role in global warming. “It’s time for the big emitters to review their policies. We have crossed what is clearly a threshold,”[1] she said. Islamabad’s sole strategy has been to seek international aid from the international community, overseas Pakistanis and from humanitarian groups. “We are in touch with our big donors… let’s hope they can come up with something that can really assist one of the most climate-impacted countries of the world in its time of need,” Rehman said.

Many are criticising Pakistan’s successive governments who have not put disaster plans in place or delivered on promises when floods previously hit Pakistan. Ali Tauqeer Sheikh, an Islamabad-based independent expert on climate change in an interview with al Jazeera explained: “In 2010, the floods were riverine in nature, which means they mostly impacted areas around the Indus River and they were mostly predictable. This time, there are multiple types such as urban flood, flash flooding and floods caused by glacier burst. What we are seeing here in the country is development deficit. It is not only the excessive rain which is causing the issue, but rather the inadequate preparation and infrastructure.”[2] In its conclusions of the 2010 floods, Oxfam reiterated that major losses are not inevitable. “While management policies exist to minimise the impact of disasters, Pakistan’s successive governments are not implementing them on the ground.”[3]

Senator Mushtaq Ahmad Khan — a parliamentarian from Jamaat-e-Islami — said that several towns across the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa had made desperate appeals for help. But authorities failed to rescue the people there. He added that the government did not make plans to prevent the destruction despite knowing for months in advance that the monsoon rains would be unusual this year. Kishwar Zehra, another parliamentarian, bemoaned the attitude of politicians in charge of flood-affected regions. “It is highly unfortunate that helicopters are available for politicians and rulers — but not to rescue people”, she told DW. “It can be called nothing but indifference by the ruling elite towards the grief-stricken people,” she added.[4]

Successive Pakistani governments have responded to floods by reacting once the floods take place, with little in the way of proactive policies. This is despite numerous reports from previous floods detailing policy prescriptions

Governance has further hampered Pakistan’s response as there is no central government department directly dealing with the long-term effects of flooding. Whilst the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) exists it has blamed every flood since its inception on climate change. What hampers Pakistan further is disaster management receives no outlays from the national budget, it’s down to provincial governments to deal with disasters from their own budget. The Imran Khan government borrowed $37 billion from international institutes during his 3 years 7 months term. But none of this money has been seen in the areas that would develop Pakistan, such as education, health and infrastructure. Much of this money has been used to balance budgets or has been long syphoned off by corrupt officials. Nearly half of Pakistan’s national budget is going to repay the national debt, but none of the original debt has been utilised to develop the country.

Successive Pakistani governments have responded to floods by reacting once the floods take place, with little in the way of proactive policies. This is despite numerous reports from previous floods detailing policy prescriptions. The destructive effects of the flooding are exacerbated by years of poor ecological governance. Their catastrophic consequences could have been mitigated if Pakistan’s rulers had taken action. Water experts have long decried the state’s inattention to water infrastructure, which has diminished its capacity to withstand sharp increases in river flows. Another problem is deforestation, which means fewer bulwarks against raging floodwaters. Poor drainage systems also exacerbate flooding, and unregulated construction in flood zones results in more property damage and risks to lives. These are all governance issues rather than climate change.

Nations across the world suffer from floods and natural disasters and they have put in place plans to mitigate them and reduce the loss of life. China utilises cloud seeding to alter the weather, whilst Holland that sits below sea level uses flood ways, dams and canals to ensure the country doesn’t flood. Pakistan has now suffered from multiple floods in the 21st century, earthquakes alongside political and economic turmoil. Whilst the amount of rain may be beyond man’s control, the devastation they cause, is not. With the appropriate governance and policies, the death and destruction can be mitigated.

[1] Pakistan floods a ‘crisis of unimaginable proportions’, says minister (france24.com)

[2] Pakistan declares national emergency as flood toll nears 1,000 | Climate News | Al Jazeera

[3] Ready or Not: Pakistan’s resilience to disasters one year on from the floods (openrepository.com)

One comment

Hassan

9th September 2022 at 12:02 pm

Nice analysis. Pak is descending into chaos and destruction. The condition of my country is dreadful, poverty has increased gargantually, crime is on increase and pol parties are turning people into fractions. So sad.