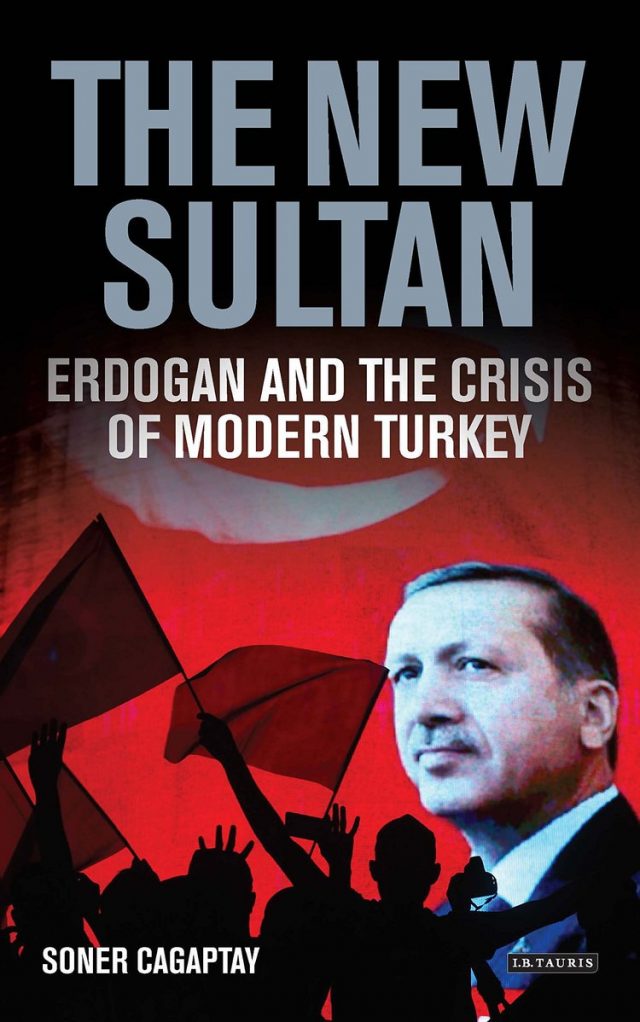

The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey

Soner Cagaptay

2017

After only three years from publishing “The Rise of Turkey: The 21st Century’s First Muslim Power” Soner Cagaptay, director of the Turkish Research Program at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, published “The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey” in 2017. In 2014 Soner believed a stable and democratic future was Turkey’s direction, but by 2017 he had a change of heart due to Erdoğan’s authoritarianism.

After only three years from publishing “The Rise of Turkey: The 21st Century’s First Muslim Power” Soner Cagaptay, director of the Turkish Research Program at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, published “The New Sultan: Erdoğan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey” in 2017. In 2014 Soner believed a stable and democratic future was Turkey’s direction, but by 2017 he had a change of heart due to Erdoğan’s authoritarianism.

Whilst Cagaptay condemns Erdoğan and his policies, where I found this book useful was the background and context as well as Erdoğan’s political upbringing. This book charts Turkey’s political evolution from the time of Mustafa Kemal to the current day and looks at Erdoğan’s upbringing in the tough Istanbul district of Kasımpaşa.

Cagaptay charts how Erdoğan started out among nationalist Islamists in student politics of the 1970s. It was a turbulent decade in Turkey, as left-wing and right-wing groups waged bloody turf wars across the country. Cold War political Islam was defined by staunch anti-communism and scepticism about the capitalist West, believing that both were stoking social and political turmoil.

Political Islam was inadvertently helped by neoliberal economic measures and the official “Turkish-Islamic synthesis” ideology imposed after the 1980 military coup. Erdoğan rose gradually through the ranks of Islamist politics through the 1980s and his breakthrough came when he was elected Istanbul mayor in 1994. His municipal administration earned a reputation for pious competence, but in 1999 he was barred from politics and jailed after delivering a rabble rousing religious poem at a public rally. The ban was lifted and he became Prime Minister in 2003 after the new Justice and Development Party (AKP) entered office.

Cagaptay then covers the AKP in office from its apparent commitment to Turkey’s EU membership bid to challenging the political influence of the military. The breakdown of the alliance with Fethullah Gülen and dealing with the Kurdish question are also outlined in detail.

The book strikes a pessimistic tone about Turkey’s future. Cagaptay believes Turkey has passed a dangerous rubicon as Erdoğan wields his iron fist. Cagaptay believes: “Turkey is in a deep crisis, divided between those who love Erdoğan and those who hate him. Erdoğan knows that he cannot continue to transform Turkey into a conservative Islamist Middle East state as long as the country is a democracy. I take the view in my book that he is abolishing democracy because of this, and I think he will take further steps in that direction in the next two or three years. The different groups that hate and despise Erdoğan and together make up half of the country will not be able to agree to overthrow him, nor will they submit to him. In this respect, Turkey is unfortunately heading into an even deeper crisis.”

Cagaptay uses a democratic lens throughout the book and this is why he’s critical of Turkey’s current direction. He is a historian by training and is an expert on Turkey–US relations and Turkish nationalism and what he does well in this book is provide the historical context and detail on the various political, social and economic trends that will help anyone trying to make sense of Turkey. The book provides excellent detail on Turkey’s domestic politics since the early 20th century and this is the main reason why someone should read this book.