The Rohingya crisis entered its fifth year in 2021 and sees no end in sight. This week is also one year since the 1st February military coup and on the anniversary, Myanmar remains in deadly civil conflict. The lack of commitment, absence of willingness, sporadic killings in refugee camps and foreign interests all remain major obstacles to solving the crisis.

Myanmar’s oppression of Rohingya Muslims is historical. During the late 1970s military operations were launched in the Rakhine state to expel the ‘foreigners’ (a term for Rohingyas always endorsed by the Myanmar military junta), which triggered the first Rohingya refugee problems. In 1982, the Citizenship Law after the repatriation of Rohingyas further deteriorated the situation of the Rohingya people. Following elections in 1991, the military launched another operation against the Rohingyas. Later, bitter Buddhist nationalism driven by sectarian violence led to more Rohingyas being displaced in 2012. But, Tatmadaw’s late 2016 and mid-2017 military operation crossed the limits of past atrocities with around 800,000 Rohingya Muslims being displaced and becoming refugees in neighbouring Bangladesh. [1]

During the crisis in 2017, Bangladesh and Myanmar agreed on a joint working group for the refugee repatriation. Later in November 2017, both parties reached a deal regarding repatriation of Rohingya Muslims to Rakhine state. But the verification process led to the repatriation program not working. A secret UN-Myanmar repatriation deal in May 2018 was later disclosed by Reuters that provided no explicit guarantees of citizenship and freedom of movement.[2]

Getting into Tatmadaw’s thinking

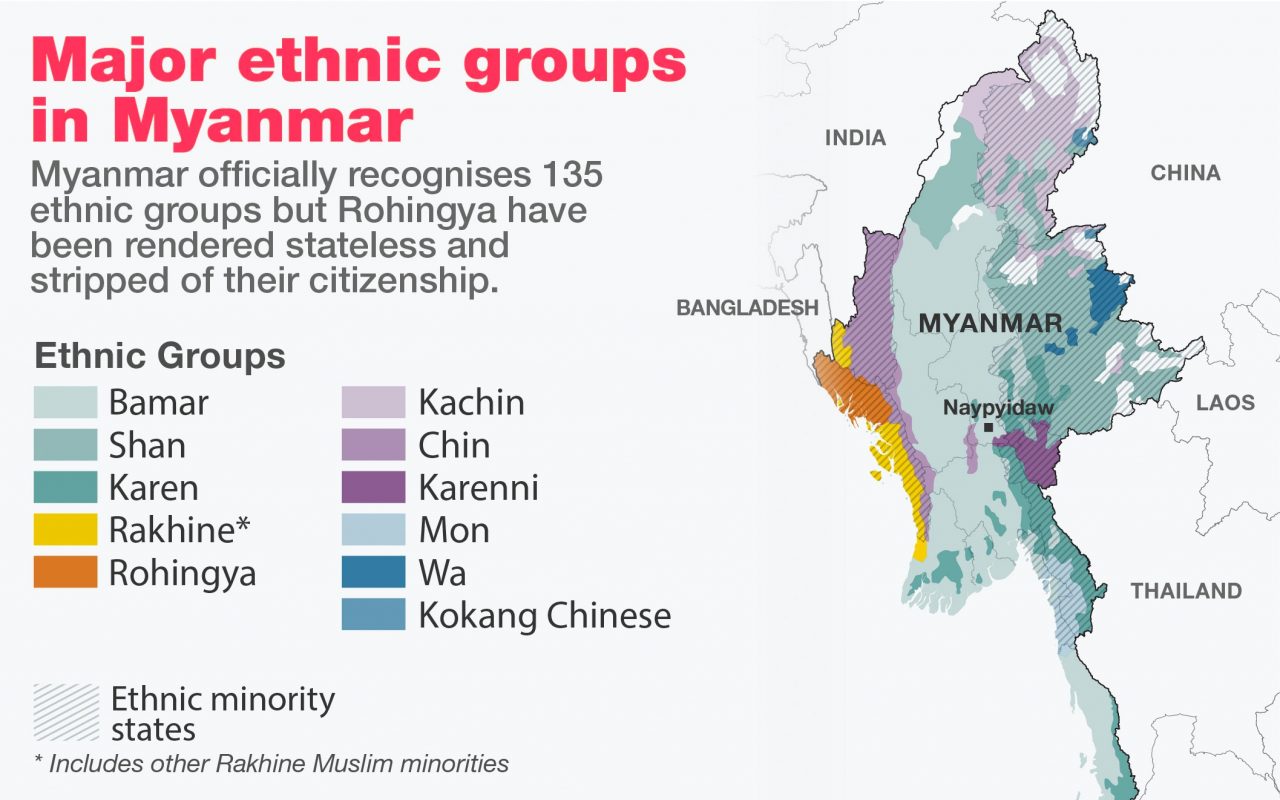

The Rohingya Muslims are the latest victim of geopolitics. They are sandwiched between Myanmar’s discriminatory domestic politics along with ethnic fault lines and vested interests of major powers namely, China and USA. From the very beginning of its independence, Myanmar has been a fractured country with a staggering 135 ethnic groups. It has 21 major ethnic armed groups, some of which maintain large militias and control areas roughly the size of Belgium[3], a direct result of the divide and rule strategy of the colonial era. Myanmar’s military junta saw its main challenge of unifying the country by controlling its restive mountainous region. The majority of Myanmar’s populations are Bamar, but ethnic groups make up nearly 30% of its population. This means if any ethnic group gained sufficient strength it could threaten Naypyidaw. The Junta government found a solution in isolating itself and pitting its various ethnic groups against each other.

Buddhist nationalism

Buddhist nationalism has played an important role in the Junta’s quest for unification of the nation. 90% of Myanmar’s population including several major ethnic groups are Buddhist. Buddhism has been in a historic conflict with the Muslims of Bengal. Although Buddhism’s natural birthplace was in the Indian subcontinent, subsequent Indian Hindu kings went to war against the Bhuddists that led to the near extinction of the religion. This is why from the Rakhine state of Myanmar to South East Asia, Buddhism has maintained a continual presence rather than its birthplace, India.. The Rakhine state has become the hot point of contention between Rakhines and Rohingyas. Rakhines close proximity to Bangladesh is what gives it the higher concentration of Muslims in Myanmar. The Rohingyas are almost one third of the total population of the Rakhine state, which is a major concern for ethnic Rakhines. Rakhines believe if the Rohingyas are recognized then their political power will decline.

Rakhine state is situated on the western coast of Myanmar. It is home to Myanmar’s major offshore natural gas field. Rakhine state is also an important part of China’s BRI project which is the starting point of a major pipeline to China’s Yunnan province and the location of a huge Special Economic Zone.

China-US Conflict

China sees Myanmar borderlands as a strategic buffer for its distant Yunnan province and an alternate supply route to the Indian Ocean to reduce dependency on the vulnerable Malacca Strait. The BRI’s pipeline project and Special Economic Zone are the greatest example of Chinese interest in Myanmar. Historically, China supported both Myanmar’s ethnic insurgency groups and Naypyidaw, keeping both as pressure points against each other. After the military junta’s five decades of continual reign, it opened up to the world through democratic election in 2011. After this, China lost its influence over Naypyidaw that it once had. On the other hand, the military also drifted towards the west and India to reduce its dependency on China. After the 2017 refugee crisis, when the international community was raising the slogan of human rights against the military junta, China again regained its influence in Myanmar. China’s role as mediator between Bangladesh and Myanmar is also noticeable.

Refugee Camp Murders

Perhaps the most complicating factor for Rohingya repatriation is several high scale murders at refugee camps in Bangladesh. In September 2021, prominent Rohingya leader Mohibullah was shot to death in a sprawling camp in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. Mohibullah, who once visited White House and met Trump, was an advocate of Rohingya human rights and repatriation. The US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken was “deeply saddened and disturbed” by the murder of Mohibullah.[4] Mohibulah’s relation with the US was noticeable. In October 2021, a shooting and stabbing took place at a Rohingya camp killing seven people. The grisly incident followed Mohibullah’s murder. In reaction, Bangladesh Foreign Minister Dr AK Abdul Momen said, “violent activities including murders are happening in the Rohingya camps in a planned manner to prevent repatriation. Such incidents are a matter of real panic.”[5] Since 2017, around 50 Rohingya leaders and activists have been assassinated.

From the very beginning of its independence, Myanmar has been a fractured country with a staggering 135 ethnic groups. It has 21 major ethnic armed groups, some of which maintain large militias and control areas roughly the size of Belgium

ARSA: Phantom of Junta?

Arakan Rohingya Solidarity Army (ARSA) is the lone Rohingya insurgent group. According to the International Crisis Group (ICG), ARSA was led by Rohingyas living in Saudi Arabia. The ICG says ARSA’s leader is Ata Ullah, who was born in Pakistan and raised in Saudi Arabia. ARSA said they are fighting on behalf of Rohingyas, who have been denied the most basic rights, including citizenship.[6] But their actions are dubious. Prominent Bangladeshi daily published an investigative article on ARSA after Mohibullah’s murder. Based on different segments of Rohingya communities, the report indicates that ARSA is working on behalf of Tatmadaw.[7] ARSA’s entry into the already complicated Myanmar scene was also dramatic. In 2017, the day after the release of former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan’s report on Myanmar government’s ill treatment of Rohingyas, ARSA launched coordinated attacks on Myanmar military outposts, killing dozens of troops. In response, Myanmar military’s action created the latest Rohingya exodus. Although, ARSA is lightly armed and a group of few hundred members, Myanmar military’s response against ARSA was overwhelming in terms of its action against United Wa State Army (an ethnic Wa armed group) which has 30,000 strong army and fighting against the Myanmar military near Chinese and Thai borders.[8]

The Rohingyas find themselves in a vicious cycle of geopolitics involving both regional and international powers, as well as internal forces. The recent coup in Myanmar which ousted democratic leader Suu Kyi makes it even more likely that the military leaders will once again take the country into isolation. This will push the repatriation talks back into the wilderness.

[2] Secret U.N.-Myanmar deal on Rohingya offers no guarantees on citizenship | Reuters

[3] Leadership change looms for armed group key to Myanmar’s peace process | Reuters

[4] On the Killing of Rohingya Muslim Advocate Mohib Ullah – United States Department of State

[5] Violence in Rohingya camps to prevent repatriation: FM (tbsnews.net)

[6] Myanmar’s Rohingya Crisis Enters a Dangerous New Phase | Crisis Group

[7] Arsa presence at rohingya camps: Everybody knows Few dare speak | The Daily Star

[8] United Wa State Army – Wikipedia