As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) marks its 100-year anniversary on 1st July 2021, in this Geopolity series we asses where China stands today and its prospects for the future

As the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) celebrates its centenary China’s officials are going to great lengths to hammer home the message that the CCP alone can restore China to what Beijing considers the country’s rightful place as a global power. China today is vastly different to the era in which the CCP emerged, in fact the Chinese nation is in a very different place to where it was not just when the CCP emerged in 1921 but to where it was just a few decades ago. This history is what the CCP is going through great pains to show the Chinese people that the CCP has not just saved China but only it can navigate China to a position of global dominance.

Century of Humiliation

At the beginning of the 20th century China was in the midst of the most tumultuous period in the country’s history, one that featured an incessant series of wars, occupations and revolutions. China had for four millenia been governed by successive dynasties, but the rise of Europe and its colonisation of the world saw the Qing dynasty fall in 1911 as China came to be swallowed up by numerous colonial powers. The four millennia old civilisation was on its knees. The Qing government was forced to sign a series of unequal treaties beginning in 1842 in the first opium war. It conceded Hong Kong, Macau and other major port cities to the British Empire. The Chinese haven’t forgotten this shame. This period is carved into the minds of the Chinese people, who for long considered themselves the world’s pre-eminent civilisation. China had fallen behind the superior technology of the West over the centuries, an imbalance that finally came to a head with the loss in the Opium Wars.

The areas of China that didn’t come under colonial control saw the rise of numerous warlords. Sun Yat-sen was one warlord who attempted to replace the Qing dynasty by forming the Kuomintang of China (the Chinese Nationalist Party). He had no army to command and an ineffective government. The most influential warlord Chiang Kai-shek eventually replaced Sun Yat-sen as the leader of the nationalists. As dictator Chiang Kai-shek attempted to unite China, but due to the Japanese occupation in the north of China, foreign interference and the lack of support from the rural areas (the Nationalist’s support came mainly from the urban areas of China), China remained in chaos.

At the beginning of the 20th century China was in the midst of the most tumultuous period in the country’s history, one that featured an incessant series of wars, occupations and revolutions

It was in this chaos that the Chinese Communist Party emerged. Mao Zedong, whilst working at Peking University in the 1920s became a founding member. The first CCP congress was held in Shanghai on 1st July 1921 and attempts to trigger an uprising against the Nationalists all failed by the Communists. The Communists temporarily allied with the Nationalists under the United Front during the Japanese invasion from 1937–1945. When the Japanese forces surrendered in 1945 the civil war resumed between the Communists led by Mao and backed by the Soviet Union and the Nationalists, led by Chiang Kai-shek and backed by the US. Mao took the long march to the interior of China, where he raised a massive peasant army and in 1948, returned to expel the Nationalist leaders, who, along with their government and supporters escaped to the island of Taiwan. Taiwan would remain separate from Communist control and even today the CCP look upon the island of Taiwan as a rebel province that is part of mainland China. The victory over the nationalists led Mao on 1st October 1949, to proclaim the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

Mao’s Communist Dead End

The Communists faced a daunting task. The central government had weakened and lost control of the country. Japan had occupied and destroyed much of the country and warlords had taken over most of the buffer regions. Japan left Manchuria after its defeat and this region came back under Chinese control, Outer Mongolia was under Soviet control which was extending its influence into Inner Mongolia and Tibet and Xinjiang, they were effectively beyond the reach of the central government.

In 1950, Chinese forces captured Tibet’s border area, forcing the Tibetan government to accept China’s Seventeen Point Agreement. In 1956 China repudiated this agreement, forcing the Dalai Lama to flee. In Xinjiang many Uyghur Muslims died in clashes that broke out in 1949 between the Communist regime that took over and abolished the independence of the territory and annexed it to the Republic of China. The Communist regime tried to empty the region’s population of Muslims by forcibly re-settling them to China’s other provinces. The Communist regime supported Mongolian militias during the war against Japan and sent them into Manchuria as guerrilla fighters. After the war ended in 1945 the Communists influence over the fighters was enough to bring both inner Mongolia and Manchuria regions under communist control.

Mao re-enclosed China, re-established Beijing as China’s capital, centralised power again and wanting to end the huge inequality between the coastal region and the rest of China, Mao expelled foreigners in the coastal areas. Mao had recreated a united China.

Politically, China became a communist state, communism became the country’s worldview. Mao believed that communism would eventually triumph over all other ideologies, but under Mao, Chinese leaders interacted little with the UN and other major institutions of the international system. In fact, China was left behind completely as the US constructed the post-World War order. China viewed itself as a revolutionary state, self-consciously determined to undermine and overthrow the US-led global capitalist order. It did this by portraying itself as a representative of the developing world through its support for the non-aligned movement through much of the Cold War, practically meaning China played virtually no role beyond its borders.

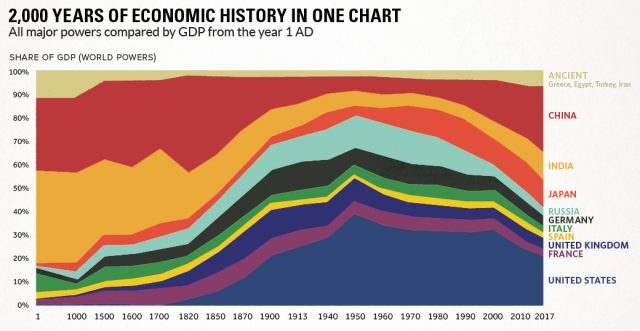

The CCPs main challenge was feeding a population of 550 million. China along with India throughout history had always been the world’s largest population. China needed to develop its economy after a century of devastation by foreign powers. This was to be achieved, according to Mao via communist lines.

The Great Leap to nowhere

The ‘Great Leap Forward’ in 1958 was a hugely ambitious plan that attempted to use mass mobilisation to catch up with the industrial standards of the US and UK in just a few short years. The plan attempted to collectivise all aspects of life (even cooking pots), the strategy saw farmers pulled off their land to engage in ill-advised rural industries such as small-scale steel plants. The strategy led to widespread famine and the death of 30 – 40 million people. The years of the Great Leap Forward saw economic regression, it was a disaster of epic proportions. The negative effects of the Great Leap Forward were studied by the Communist Party and Mao was criticised in the party conferences and came to be marginalised within the Communist Party

Mao hit back and initiated the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Mao announced China was lacking in revolutionary spirit. He targeted the party bureaucracy and accused them of leading the country into stagnation. He accused the party bureaucracy of dragging their feet in implementing his edicts. The Cultural Revolution was a campaign to shake the bureaucracy’s hold on power. Brigades of students were mobilised to make war on thoughts that were deemed reactionary. These Red Guard students roamed the country seizing control of government offices, destroying cultural artefacts and terrorising the population. The army stepped aside leaving the party bureaucracy to direct attacks. Many leading Communist cadres were killed after being identified as reactionaries. Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping were purged with Liu later dying in prison. The campaign would not come to a complete end until the death of Mao in 1976, when the military demobilised the Red Guards leading to the end of another period of instability in China’s long and turbulent history.

‘Open and Reform’

The death of Mao led to the emergence of the reformists led by Deng Xiaoping. Under his leadership an analysis of the nation was undertaken by technocrats from the CCP. The analysis presented at the 3rd Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in 1978, concluded that the prior efforts to develop China, the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, had been failures. Mao’s theory of continued revolution under socialism was abandoned and mass class struggle came to an end. It proposed a new comprehensive policy for China called the “Four Modernizations” of industry, agriculture, national defence and science-technology.

The reformists’ view was that developing China economically was not just an aspiration but necessary for the survival of the Communist party. Whilst the CCP was seen as the saviour of China after WW2, its stewardship of the country since then had been a disaster. The CCP recognised that it had failed to develop the nation and the years under Mao were leading to questions about the legitimacy of the CCP. China’s strength on the eve of its development was its huge population and large labour force. They were not particularly skilled in modern methods, but such a large labour force if used correctly and deployed into the right areas could lead to a huge increase in production.

The abandonment of Communism and the CCPs stewardship of China from 1979 turned out to be a spectacular success. The CCP today rules over a China that is very different not just from a century ago but even just four decades ago.

21st Century Dynasty

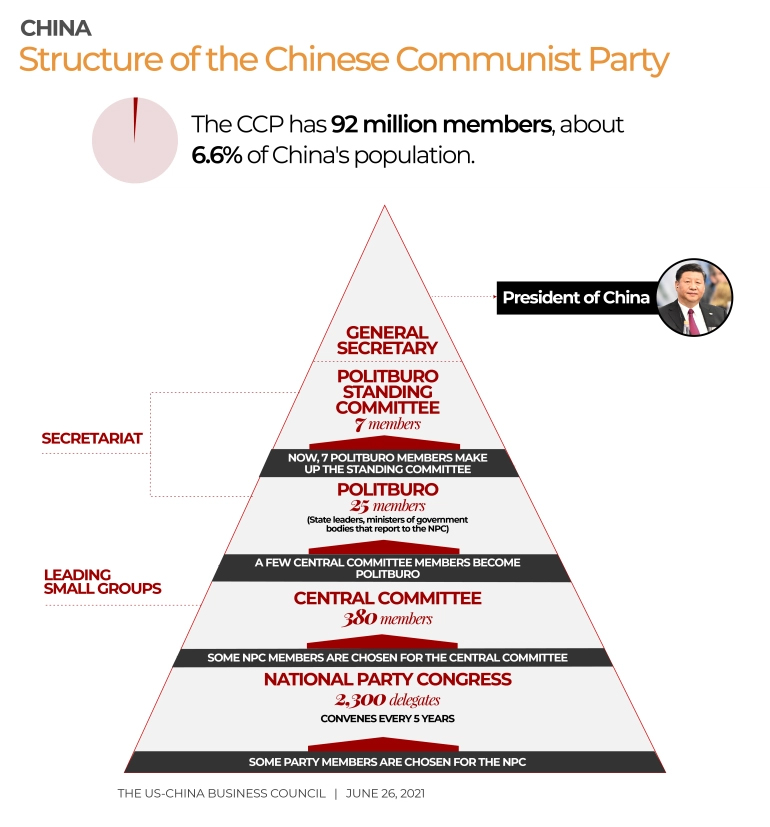

Today, China’s political system is a bureaucratic one-party state. It is in principle highly centralised, but in practice substantially de-centralised. China’s political system has evolved since 1978 from the cult personality of Mao Zedong where today decisions are made through consensus. Authority resides in no individual but in the Communist Party which sits atop the political system and selects leaders who are subject to term limits and mandatory retirement ages.

China’s top leader holds three concurrent positions in order to be the supreme leader. General secretary of the communist party, chairman of the central military commission (which controls the army) and state president, a mainly ceremonial role that confers ultimate control of the government. A leader must hold all three positions, but especially the first two to exercise full control of the state. In 1992 at the 14th party congress Deng Xiaoping, who had been China’s paramount leader since 1978 retired and transferred control of the party, military and government to the new president Jiang Zemin. In 2002 Zemin retired and ceded control of the party and government to Hu Jintao, he did not give up chairmanship of the central military commission for another two years. In 2012 Hu retired and Xi Jinping assumed control of the party, government and military.

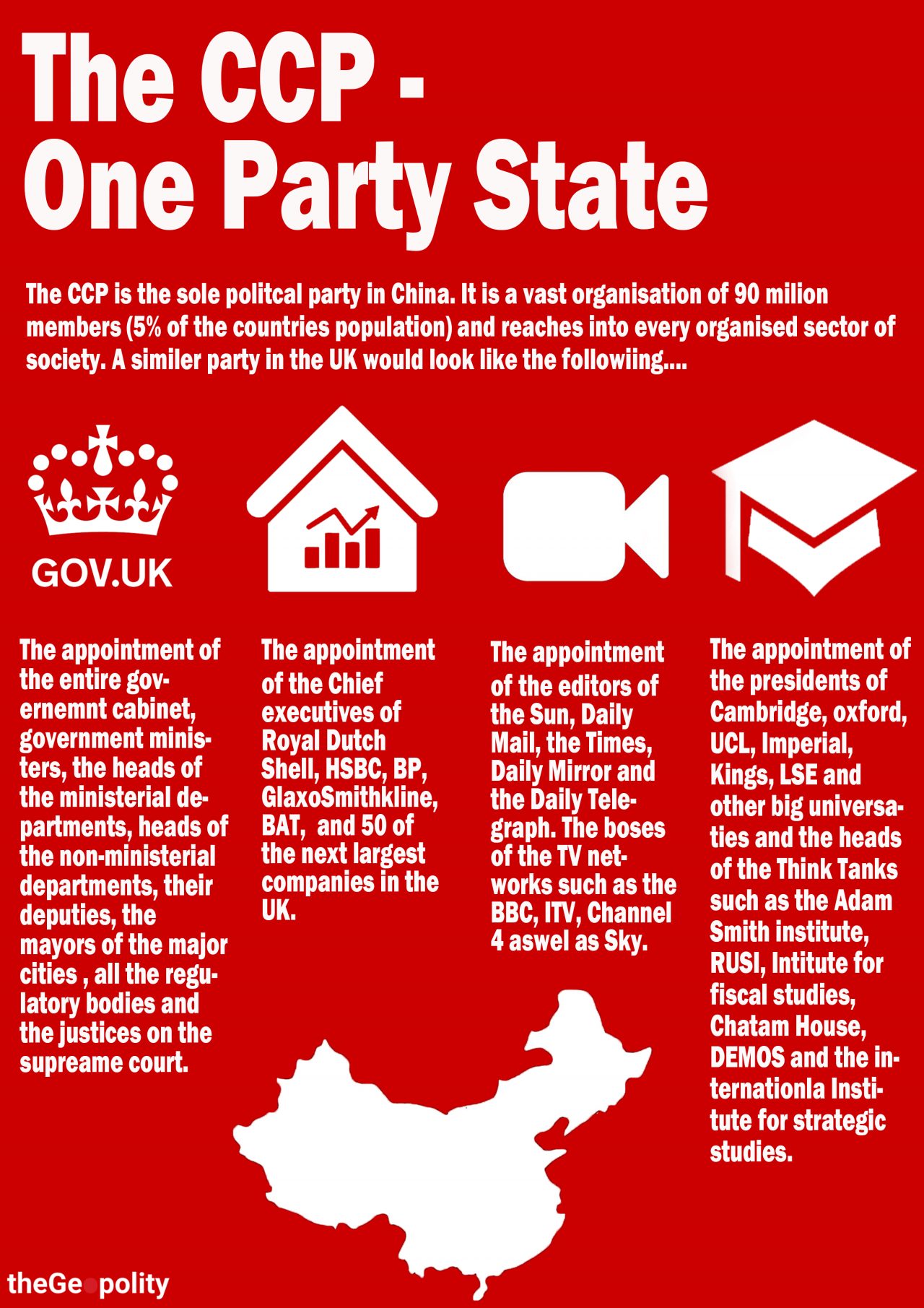

China is a one-party state but rather than a tiny cabal of secretive leaders, it is a vast organisation of around 92 million members and reaches into every organised sector of society including the government, courts, the media, companies (both private and state owned), universities and religious organisations. Top officials in all these organisations are appointed by the CCP.

The party no longer attempts to control every individual’s life as it tried doing in the Mao era, but it does seek to heavily influence every sphere of organised activity. Whilst China is seen by many to be a highly centralised nation, the reality on the ground is local governments enjoy a high level of discretion and autonomy. A 2004 IMF study found that in the period 1972-2000 the share of government expenditure that takes place at the sub-national level was 25% for democracies and 18% for non-democracies. In China from 1958-2002, this figure was 54% and by 2014 it reached a staggering 85%. For an authoritarian nation this level of fiscal decentralisation is extremely high.[1]

China is run through a pyramid structure with several layers of bureaucracy between the top leaders and specialised agencies. Most of these layers lay within the Communist Party structure and often their activities are cloaked in secrecy. At the top of the pyramid is the standing committee of the party’s politburo consisting of 7 members with decisions requiring consensus. This committee sits within a broader 25 member politburo, which meets several times a year and ratifies major decisions. Below the politburo are the ‘leading small groups’ which the party organises to coordinate policy on major issues. Below this is the State Council, chaired by the premier, which is the highest organ of government and is equal to the cabinet in most national governments. Below the state council are the ministry level bodies, the most important of which are the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Finance (MOF), the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM), which also handles foreign policy issues and the Peoples Bank of China (PBC).

A lot of power is concentrated at the top of this structure, but Chinese leaders rely upon provincial leaders to come up with policy to execute such decisions, making provincial leaders important national decision makers. Although China is run by a centralised command structure in practice it is decentralised, which is necessary due to its sheer size and population of the country. The CCPs discipline and control of the bureaucratic appointment system throughout the country prevents China from splintering apart and enables the formulation and implementation of coherent strategies.

The CCP has a unique position in China and is unparalleled anywhere in the world. It is not viewed like the republican party in the US or the Conservatives in the UK but is seen as a civilisational party that played a central role in expelling the Japanese during WW2 and bringing stability to the war torn nation. This makes the CCP the sole political party in China that doesn’t have to worry about other competing parties or election cycles. The CCP does have elections, but these are really transitions where one set of Party officials hand over rule to another set of party officials. All the executive organs we are accustomed to around the world, in the case of China, take place within the CCP rather than the executive, judicial and legal realms all being separate. This gives China the stability it needs, especially due to the large territory that it needs to manage. The CCPs stewardship of the economy is what gives it credibility and it is now the latest in a long list of dynasties to rule over the middle kingdom.

In the next part of the series we look at how the CCP was able to turn China from a poverty stricken nation into an economic juggernaut

1 Pierre Landry, Decentralized Authoritarianism in China (Cambridge University Press, 2008), pg 6– 8

2 comments

Abu Pikachu

2nd July 2021 at 11:43 pm

Very interesting, very much looking forward to the rest of the series.

Do you believe the muslim world can learn anything from China’s political structure and them turning into a powerhouse?

Adnan Khan

4th July 2021 at 2:45 pm

I think there are a number of lessons that can be learnt from China, there are also some lessons that can be learnt that we should NOT emulate also.

Mao realised that the only way farward for China was to kick out the colonialists, remove foreign interference and ensure the Chinese ran China. This is what Mao and the communists did, realising there was no independence by aligning or working with any colonial power.

unlike China today, the Muslim world is a hotbed of foreign intrigue because the Muslims rulers are the door through which the colonial nations enter our lands. They don’t seemed to have learnt this lesson.

When the CCP took power they inherited a nation that was well behind the other world powers. They lacked modern industry and struggled to even feed their own population. Mao and his comrades understood they needed to change this and set about the long-term development of China.

Despite possessing some of the world’s key resources in abundance, no such long-term strategy exists in the Muslim world, but rather short-term economic projects have been pursued or foreign-born strategies implemented under the guise of free markets and free trade. The Middle East nations, who have abundant energy resources, have never used this to build state of the art infrastructure (beyond malls and hotels of course) or to acquire modern technologies. Saudi Arabia could buy the technology and the skills know-how and spend a single generation ensuring these were learnt and adopted by her domestic population, but the Saud family is more concerned with maintaining its throne and investing the Ummah’s wealth in Western financial markets and bailing out Western corporations.

China in her foreign policy doesn’t advocate any values, she just wants economic deals, investment and markets. There is no ideology or system for the world. Not having or advocating values has meant she is unable to integrate the people of Hong Kong or Taiwan or Xinjiang into mainland China. A lack of unifying values has resulted in a very heavy-handed approach to maintaining rule for the CCP

China’s development was unique to her particular reality and is not straightforward for others to replicate . The Muslim Ummah possesses Islam that not only unites people but it provides a framework to run an economy and also a framework to organise society, and amalgamates different people. What we can learn from China is there is no future in adopting Western ideals or integrating into the global system constructed by the West. However, removing foreign influence and being independent, is where the Muslim world needs to look.