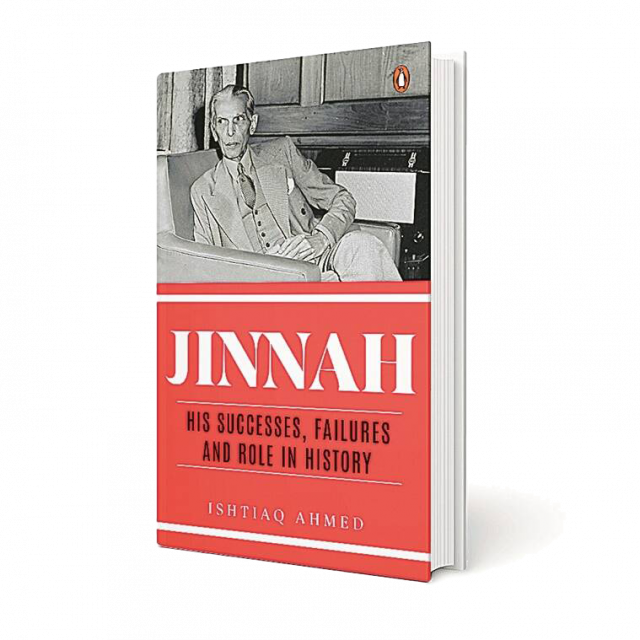

Jinnah: His Successes, Failures and Role in History

By Professor Ishtiaq Ahmed

2020

With the lockdowns due to the Covid pandemic I was looking to catch up on my reading and took the opportunity to finally do some reading on the history of South Asia and the controversial topic of the partition of India.

There is no shortage of literature written on South Asian history with some vilifying Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan who caused the division of the continent that caused much bloodshed due to communal riots. Whilst other authors celebrate partition and consider Jinnah Quaid-e-Azam (great leader) and break down the two-nation theory. I came across Professor Ishtiaq Ahmed, of the Stockholm University promoting his book where he questions much of the mainstream narrative. Ahmed, a Punjabi from Lahore, who was born in February 1947, some six months before Pakistan, makes extensive use of contemporary records and archival material as well as declassified British reports from the era. Looking at the role of Muhammed Ali Jinnah I thought is a good place to start to make sense of the partition.

In 800+ pages Ahmed busts many myths surrounding Jinnah and puts into perspective British plans, which unlike Jinnah’s remained the same. This was to maintain India divided or united as a bulwark against Russian expansion into South Asia.

Ahmed spends much of the book analysing the phases Jinnah went through from the early 20th century until Jinnah’s death, a year after the 1947 partition. Jinnah, Ahmed believes, went through three phases in his life where he changed his views and adapted to the circumstances in the region.

The first phase saw Jinnah join the Indian National Congress (INC) in 1913 as an Indian nationalist, who even opposed the formation of the All-India Muslim League (AIML) as well as the Khilafat movement. The Lucknow Pact was the major achievement of this period which saw the INC give concessions to the Muslims in order to achieve self-rule in India from the British. The core argument Jinnah set forth in defence of the Lucknow Pact was directed at demolishing the assertion of the disciples of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan’s British-loyalist Muslims, that if the Muslim minority sought concord with Hindus it would inevitably mean permanent domination of the Hindu majority. Jinnah ridiculed that possibility. Jinnah substantiated his stand, by arguing that India would not be governed by Hindus or Muslims but ‘by the people and sons of this country’. On such a basis he demanded the ‘immediate transfer of a substantial power of the Government of the country’ to the people of India.

With the rise of Gandhi who had returned from South Africa in 1915 where he led civil disobedience against the British, Jinnah moved into his second phase. Gandhi was more radical than Jinnah, calling for non-cooperation and challenging British rule. Jinnah believed in the use of constitutional means and more self-governance within the British empire, like Canada, Australia and South Africa. It was according to Ahmed, a combination of psychological or personal reasons and strategic and tactical reasons that Jinnah left Congress. Jinnah did not want to be in the shadow of Gandhi and worked to become the main leader of the sizeable and influential Muslim minority. Insofar as British rule and control over India were concerned at that stage, the differences between Jinnah and Gandhi were of no great consequence to imperialist interests.

This phase of Jinnah’s life revolved around communitarianism, where he argued that Muslims were a distinct community. Jinnah advocated that India was inhabited by discrete religious communities which did not share any cultural capital that would enable them to function as a cohesive nation. He wanted constitutional safeguards that would prevent perceived Hindu majoritarian domination in a united India. He was calling for a confederation.

By 1924 Jinnah had become the leader of the AIML, which was largely a platform for a narrow elite group of landowners and conservative notables. Membership was restricted, few paid membership fees and the party lacked central leadership and organisation. This situation continued into the 1930s.

The third and key phase of Jinnah’s life was from 1940 where he made his Lahore Declaration and proposed the two-nation theory. Jinnah insisted Muslims and Hindu’s were different communities, and both could not live together. The context at the time was Britain’s deep involvement in World War 2 (WW2) and signing up the Indian army to this to the great frustration of the INC, who believed the British had no such right. Gandhi launched the Quit India Movement, whilst Jinnah joined and actively promoted British interests by helping the recruitment of Muslim officers for Britain’s WW2 effort. Muslims from Punjab constituted the largest faction in the British forces. It was here that one sees the meteoric rise of Jinnah as a leader. Ahmed provides ample evidence here of collusion between the Viceroy Victor Linlithgow and Jinnah to checkmate Gandhi’s Quit India Movement and Jinnah trying to gain British support for recognition that Muslims were a distinct and separate community to the Hindus.

The final phase of Jinnah’s life was of Muslim nationalism and the demand for partition as a separate country, which came right at the end as British officers had concluded the INC wanted to be independent and build relations with the Russians after partition, whilst Jinnah agreed to keep Pakistan in the commonwealth and to make it available to Britain military bases. Partition took place as Britain saw this would achieve her strategic interests, whilst for long Britain saw a united India with a united army as a bulwark against Russia.

But the Pakistan Jinnah got was created with a divided Punjab and Bengal as Britain tried to checkmate Jinnah’s demand with the INC for a separate nation. Whilst partition provided Pakistan with the Muslim majority areas of Bengal and North-West India; Punjab and Bengal’s non-Muslim majority areas were further partitioned and went to India.

Ahmed makes other revelations. At partition the Muslim League had never found an anchor in politics as an integrated party with a vision and programme for Pakistan; instead, it had grown exponentially after the 1940 Lahore Resolution, because of an election campaign during 1945–46, which was patently communalist and populist. Jinnah only turned to the ulema and Islamic groups in 1946 as they had ground support, something the AIML lacked. It was here that Jinnah’ s messaging made use of Islamic slogans and the demand for an Islamic state became the mantra of the people, which Jinnah also picked up as it aided his goals.

Ahmed’s book establishes that the spectre of a dominant Hindu ‘Raj’ was a fig leaf for Jinnah’s intransigence on creating Pakistan, which the INC leadership tried hard to prevent. Ahmed also finds that the notions of communitarian nationalism and communal superiority were vague ideas that Jinnah used and abandoned due to their limitations. Ahmed traces the multiple transformations that Jinnah underwent during his half century long political career. Jinnah’s argument that separating Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan would usher in peace in the subcontinent was a flawed idea and his own success was only a ‘half-success’ as ‘he was rewarded with a moth eaten Pakistan’ which was very different to what Jinnah envisaged. This book deflated the myth that had Jinnah lived longer he would have put democracy on a more stable footing in Pakistan. He provides evidence that Jinnah flouted constitutional norms during his short term as Governor-General by acquiring powers not permissible under a parliamentary system thus setting the precedent for the subversion of politics in Pakistan.

Ishtiaq Ahmed eliminates some major misconceptions about Jinnah that are proposed by some historians. For this reason, this book provides a very good insight into the partition of India and is worth the read.