The discovery of a large new natural gas deposit in the Black Sea in August 2020 was hailed as a major find by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The find, which is the biggest in Turkey’s history, comes as her dependency on energy imports creates a large import bill. But after decades of being described as an energy corridor, Turkey has not seen any dividends of being geographically placed in between energy producers and consumers. With domestic demand for energy only increasing and Turkey looking to play a leading role in the regions in close proximity to her, she faces significant energy challenges.

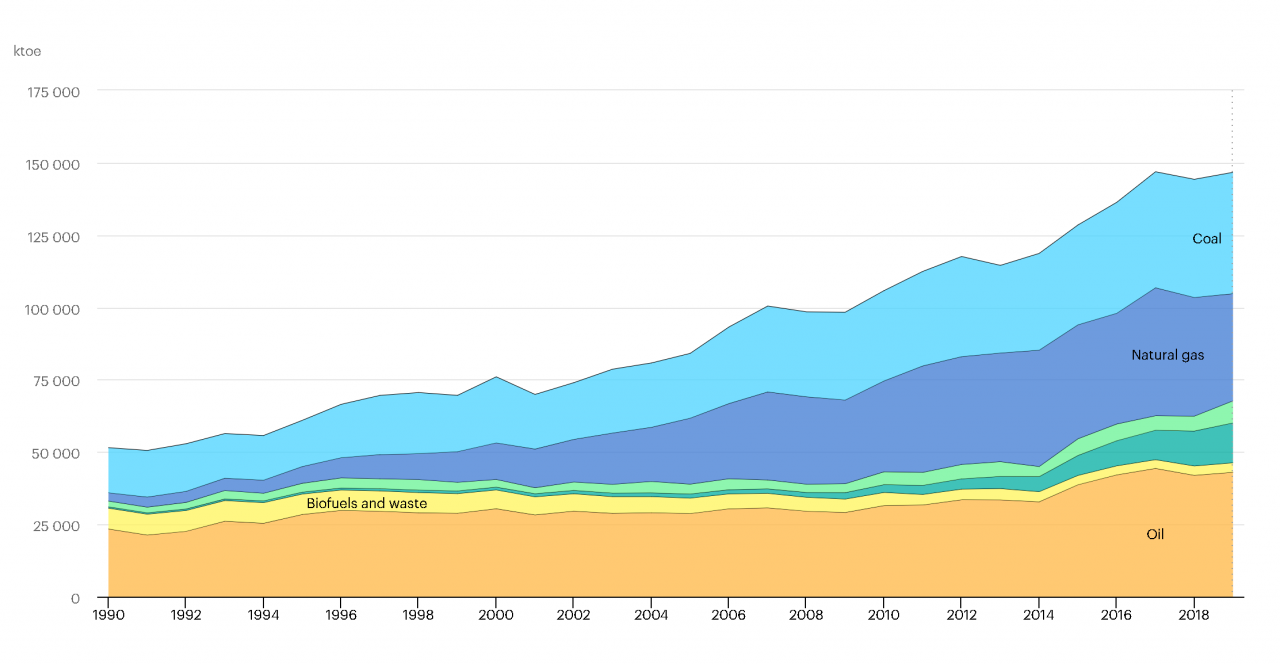

At the turn of the 21st century Turkey’s population was 63 million, today her population has grown to 85 million and by 2050 the population is predicted to be close to 100 million. Since the beginning of the century Turkey’s energy consumption has doubled. Turkey consumed just under 150,000 ktoe of different sources of energy in 2019, but only 30% of this came from domestic production. This has created a huge dependency on imports of energy with the 2019 bill costing the Turkish exchequer $41 billion!

Turkeys’ energy mix is dominated by fossil fuels.

Coal has for long been a major part of Turkey’s energy mix and it is the most abundant energy resource Turkey possesses. But her domestic production falls well short of consumption despite the fact that Turkish companies have been trying to exploit her domestic sources of coal. Coal will remain a major energy source as it provides nearly 40% of the country’s electricity. The lack of modern technology to exploit coal deposits and the lack of investment from both foreign domestic sources has seen Turkey now importing over half her coal from Colombia and Russia.

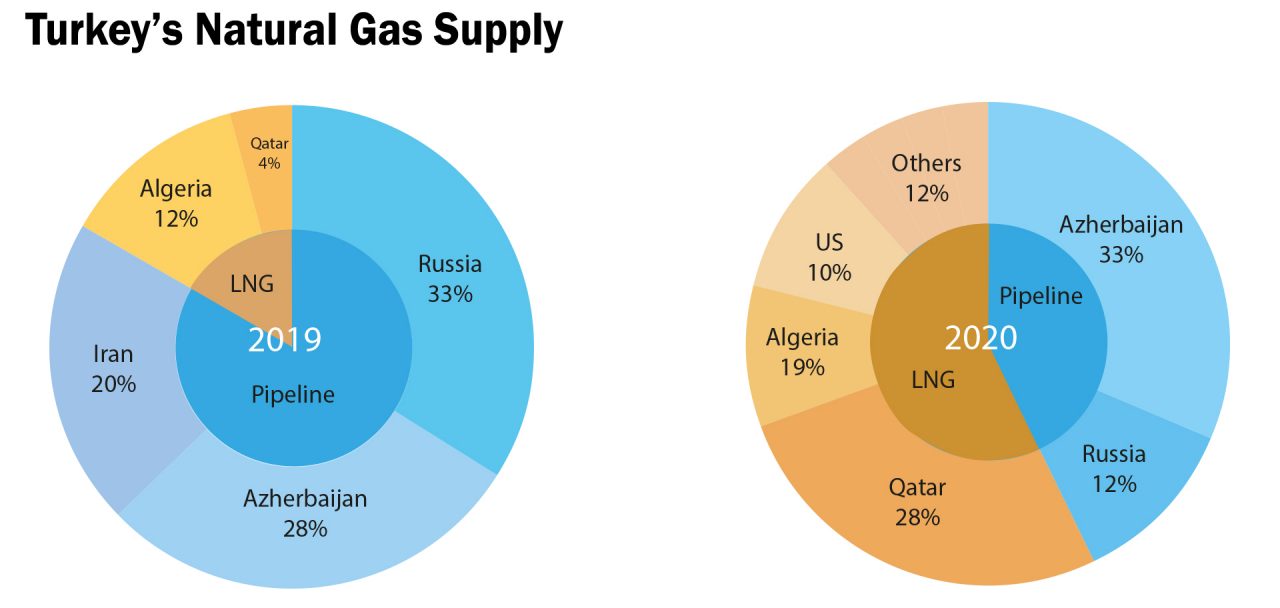

Oil and gas production has remained negligible in Turkey for years. This is what causes her large import bill, which is 20% of all Turkey’s imports. Natural Gas imports are the biggest drain on Turkey’s finances. Half of Turkey’s power plants are powered by natural gas, and this amount will only grow as Turkey’s population increases. Turkey imports 99% of her Natural gas and this is where relations with her historical foe Russia, comes into the picture. Russia has for long been Turkey’s main supplier of natural gas, which is supplied directly through the Blue Stream Pipeline that runs below the Black Sea and has a capacity of 16 billion cubic meters annually. In the recent past Russia has provided up to 60% of Turkey’s natural gas. Despite the political costs this creates for Turkey from an economic perspective, Russian gas supplies have always been more cost-effective as they travel across the Black Sea and therefore provide Turkey with the large volumes she needs. Russia and Iran, two historical enemies of Turkey, are her major gas suppliers creating a major dependency.

In 2020 Turkey succeeded in diversifying her gas supplies. Due to COVID, her national gas consumption dropped by 24% and as a result Turkey saw a major fall in pipeline gas imports and a huge increase in gas via liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports. Gas imports from Russia fell by 62% in 2020 and saw Russia fall behind both Azerbaijan and Qatar as Turkey’s largest gas suppliers. The rise in LNG imports has balanced the need for piped gas which for long created a dependency on both Russia and Iran.

Oil is the fuel of choice for transport and here once again Turkey faces significant challenges. Turkey consumes nearly 1 million bpd of oil, local production is a mere 66,000 bpd which results in imports supplying most of the country’s oil needs. Turkey receives the black fuel through two pipelines, the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline from Azerbaijan and a pipeline from northern Iraq.

Despite Turkey’s involvement in so many regional and global issues she is facing a significant number of issues at home and at the top of the list is energy, where she has major dependency on imports. The growing demand in gas consumption is fast approaching the nation’s annual capacity limits of the pipeline and LNG infrastructure. The talk for years of Turkey becoming an energy corridor or transit hub has not materialised and has remained just talk. The situation the Turkish government needs to be focusing on is keeping the nation’s lights on rather than regular rhetoric about Turkey’s independent foreign policy.

The talk for years of Turkey becoming an energy corridor or transit hub has not materialised and has remained just talk. The situation the Turkish government needs to be focusing on is keeping the nation’s lights on rather than regular rhetoric about Turkey’s independent foreign policy

Diversification

The only remnants of strategy that can be discerned from the Turkish government is diversification. With the lack of domestic energy sources Turkey has focused on diversifying her suppliers in the hope she doesn’t become dependent upon any single energy supplier. This strategy has seen some success, but the Turkish government would agree it is nowhere close to where the country needs to be.

Stalled Nuclear Plans

The most ambitious strategy would be to pursue nuclear energy, which would give Turkey the much-needed diversification and independence she seeks. Turkey has for long had many grandiose plans to develop civilian nuclear energy, but none have materialised due to technical and financial delays. Today Turkey has no nuclear power plants, but this may be ending soon. The Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant in the Mersin Province is expected to be completed by 2023 which is an agreement between Russia and Turkey to build, own and operate the power plant. Turkey and Japan signed a $22 billion nuclear deal in 2013, but in 2018 the project was abandoned due to construction costs having almost doubled. In 2018 the Minister of Energy and Natural Resources, Taner Yıldız announced that the government is working on the plans of the third nuclear plant, which is projected to be built after 2023 under the management of Turkish engineers.

The Mirage in the Black Sea

The discovery of a 320 bcm natural gas reserve under the Black Sea in 2020 was the largest discovery of energy for Turkey and its expected production will begin by 2023. The deposits will likely increase as they are part of more abundant natural gas reserves in the Black Sea that are still being drilled for. With Turkey’s current natural gas consumption of 27 bcm, which will likely rise due to her increasing population, it will last the best part of a decade. This could be increased if Turkey did not replace all imports with the new domestic resource, but unless further deposits are discovered this Black Sea discovery is not exactly the windfall it is being made out to be.

Turkey has attempted to explore her shale gas potential in the Anatolian basin in the southeast and the Thrace basin in northwest of the country. It is currently too early to judge the future prospects of Turkish shale, but deep water exploration in the Black Sea with some of the largest energy companies in the world has for the moment not lived up to expectations.

The Battle for the Mediterranean

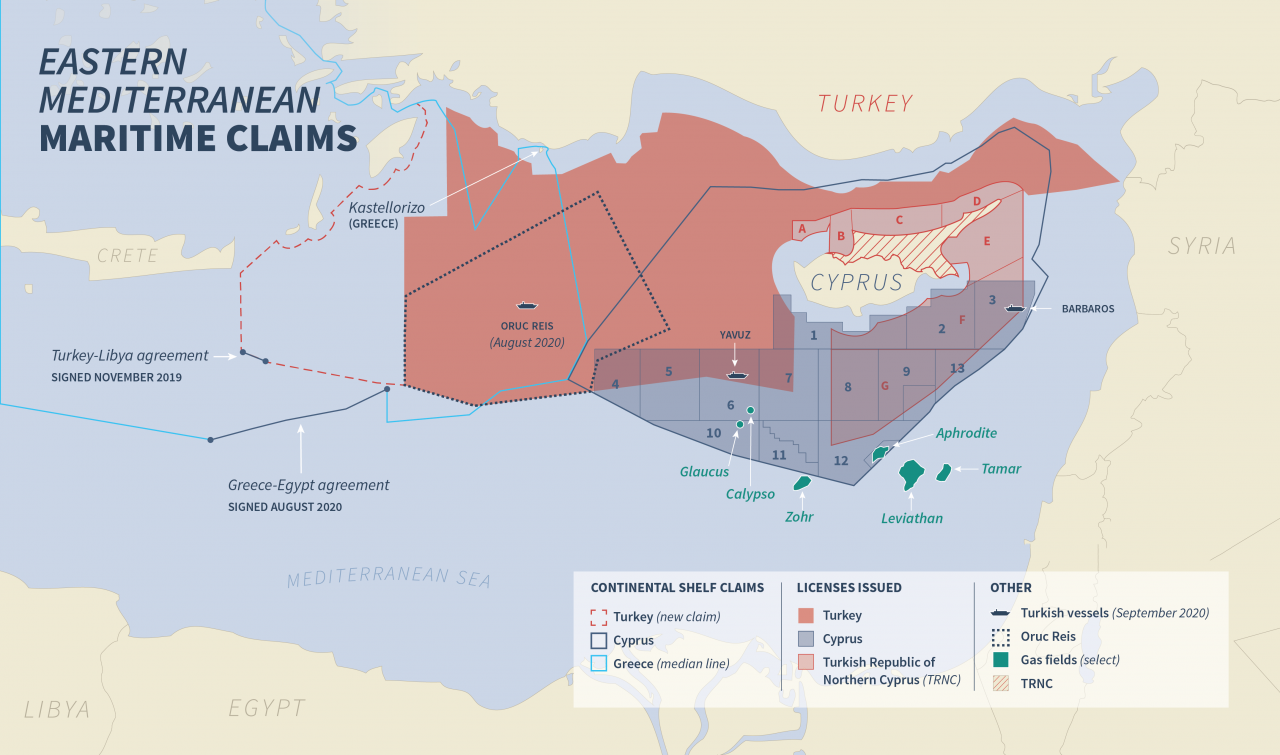

To the south of Turkey there has been a lot of activity for Mediterranean energy. With the discovery of energy in the Mediterranean, naturally Turkey has taken a keen interest in exploiting them. In 2009 the Tamar field, which is 80 km west of Haifa, was discovered with 9 trillion cubic feet (tcf ) of extractable gas. A few months later, the Dalit field was discovered in the west of central occupied Palestine with around 500 billion cubic feet (bcf) of gas. Then in 2010 a further 16 tcf of gas was discovered. This was the largest natural gas discovery in the world in a decade. Turkey began the exploration in earnest, and this led to a series of crises with Cyprus and Greece. Both nations claimed Turkey was drilling in their exclusive maritime areas: Turkey and Greece’s maritime borders. Turkey responded by announcing she had expanded her exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the Eastern Mediterranean in collaboration with Libya’s Government of National Accord. Turkey also announced she was building six new submarines to enforce her claims. The Mediterranean potentially provides Turkey with new energy sources, but with conflicting claims it remains to be seen if Mediterranean energy can help Turkey’s energy diversification strategy.

LNG Potential

Turkey could increase her LNG imports; this would give her a more diversified pool of suppliers. Turkey currently has two LNG terminals and two Floating Storage Regasification Units (FSRU) facilities. Building LNG facilities are capital intensive as they require import terminals and regasification facilities and usually require extensive upgrades of distribution networks. Currently Turkey’s LNG facilities are around the Marmara core, further facilities in the Mediterranean coast would help her energy situation, especially with gas imports from North Africa. But to achieve this Turkey will need to significantly invest in her distribution network which is currently mostly around the Marmara area of the country.

Pipeline Stalemate

Turkey is surrounded by energy rich regions and nations. To her north is the Black Sea and Russia. To her east is the Caucuses and the Caspian. To her south is both the Middle East and the Mediterranean. It’s this geography that sees many speak about Turkey’s potential as an energy hub in the region that bridges East and West. But it is Turkey’s position in the middle of both regions that makes energy pipelines so political. The Nabucco pipeline that was meant to circumvent Russian energy and carry energy from the Caucuses via Turkey to Europe was shelved in the end due to costs and politics. Turkmenistan’s energy and even increasing the energy from Azerbaijan to Europe via Turkey are some of the most political projects as they circumvent Russia. With little energy of her own, being a transit for other countries energy exports will not give Turkey the energy diversification or independence she seeks. Therefore even if there was no politics over such pipelines, constructing new pipelines from Asia to Europe would still not solve Turkey’s energy dilemmas.

Turkey has a number of options in attempting to deal with her energy challenges. Her energy challenges are however reaching a critical threshold and can no longer be put off by talk of becoming an energy hub. Without any significant energy reserves of her own Turkey cannot become an energy transit or hub, and being the middleman between energy producers and consumers does not pay sufficient commission to even begin reducing her import bill. For the moment it seems Ankara has accepted that if she wants to keep the lights on across the country, Russian gas supplies through pipelines remain the most cost-effective and reliable option. From an energy perspective Turkey is well and truly punching above her weight.