China has for long denied it was targeting ethnic Muslim Uyghurs for internment camps in its restive Xinjiang region. But the last year has seen a flurry of reports and videos showing Uighur Muslim being interned at camps across west China [1]. With pressure mounting in the Western media, who have their own agenda, now the Chinese regime has admitted to the dark reality: an island of concentration camps has been built. China’s state-run Xinhua news agency on Saturday 13 October quoted an official that the “sinicisation” of religion must be upheld. Quoting You Quan, head of the ruling Communist Party United Front Work Department, which oversees ethnic and religious affairs, he said: “The Party’s leadership over religious work must be upheld, the infiltration of religious extremism must be guarded against” [2]. Despite China’s miraculous economic rise, it has struggled with this restive region, but its importance to China is not just strategic but existential.

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) lies in China’s northwest and stretches over 1.6 million square kilometers. The region accounts for one sixth of the Chinese territory and borders eight countries. Today Xinjiang is home to around 21 million people coming from thirteen different ethnic groups with the largest being the Uyghur Muslims. It was historically a main conduit and hub for economic and cultural exchange between East and West, Xinjiang became an important section of the Silk Road. The rise of European imperialism in the 1800s saw the Russian and British empires expand into Central Asia. Imperial Russia increased its influence along China’s northern frontiers during the 19th century and as a result the Qing Dynasty brought the region under its control and established Xinjiang as an official Chinese province in 1884. But the administration faced constant resistance from the Muslim population and in the second half of the 19th century, when Qing China faced the Opium Wars, endless internal insurgencies and foreign meddling, it could not maintain a strong military presence in Xinjiang. The Qing Dynasty’s collapse in 1911 led to Chinese control over Xinjiang to virtually diminish. It would take Mao Zedong in 1949 to abolish the independence of the territory and annexe it to the Republic of China. On this occasion though Mao attempted to empty the region of its Muslim population by forcibly re-settling the regions Muslims and relocating Han Chinese to the restive region. This policy, still in force today has largely failed and is what culminated in the Ürümqi riots in 2009 [3].

Xinjiang represents one of four buffer regions for China. These buffer regions protect the heartland of Han China. The Chinese heartland is divided into two parts, northern and southern, which in turn is represented by two main dialects, Mandarin in the north and Cantonese in the south. The Chinese heartland is defined by two major rivers — the Yellow River in the north and the Yangtze in the South. This heartland is China’s agricultural region. The Han population is not spread evenly throughout China’s heartland. The population is concentrated in the east because western China has limited rainfall and cannot sustain very large populations. China is therefore a relatively narrow country, with an extremely dense population. A ring of non-Han regions surrounds this heartland — Tibet, Xinjiang Province, Inner Mongolia and Manchuria. These are the buffer regions that historically have been under Chinese rule when China was strong and have broken away when China was weak or they have been used by foreign powers to interfere deep into China. These are also the regions where the historical threat to China originated. But even aside from providing buffers, these possessions provide defensible borders for China. Xinjiang is therefore one of four regions which are vital for China’s territorial integrity.

China’s economic miracle has been predicated upon access to energy and commodities. Xinjiang is a critical region that needs to fuel China’s economic machine and it is also strategically located as a supply route. Xinjiang contains over 20% of China’s coal, natural gas and oil resources, Xinjiang has the highest concentration of fossil fuel reserves of any region in the country [4]. The oil fields at Karamay is one of the largest in China and the region has extensive deposits of coal, silver, copper, lead, nitrates, gold and zinc. Xinjiang is China’s largest natural-gas producing area and serves as an important trade and pipeline route into the Central Asian region and beyond. Xinjiang is also part of China’s quest to diversify its oil resources as the region is also a key transit route. Xinjiang is the only region in China that neighbours the Central Asian republics, Central Asian oil (and a large proportion of Russian oil) has to enter the Chinese pipeline network from Xinjiang. The first transnational oil pipeline built for this purpose was that of the Sino-Kazakh Oil Pipeline Co. Ltd. which began pumping oil in July 2006. This pipeline starts in Atasu in northwestern Kazakhstan, enters Xinjiang territory at Alashankou on the Kazakh-Chinese border, and terminates at PetroChina Dushanzi. Whilst Xinjiang missed out on China’s miracle it has literally fuelled China and for this reason it’s a strategically critical region.

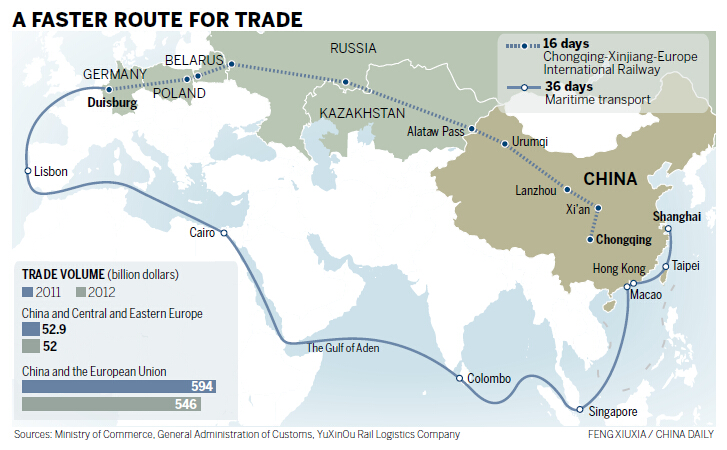

China’s economic rise saw the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZ) on China’s coastal areas where goods were manufactured for transit to the world via the oceans. The problem China has is this makes its economy dependent on the sea routes, but China does not have a military that can secure these sea supply lines. This is because the US navy controls the world’s oceans and any blockade of the many small islands that surround China in the region would lead to the crippling of its economy. This is where Xinjiang comes into the picture as it was historically China’s key land route to the world. Western China provides extended access to the Arabian Sea through Pakistan, and to the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf. China could access Pakistan, Central Asia, the Middle East and the whole of Eurasia and beyond via Xinjiang and transport resources overland and avoid excessive dependence on vulnerable sea routes. It is for this reason China’s colossal Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will have multiple sections run through Xinjiang to connect the entire country to Eurasia and beyond. In this way, Xinjiang has become something of a geographic lynchpin for economic connectivity across Eurasia. The whole BRI initiative promises to have huge implications for China’s trade relationships and global influence and at the centre of this is Xinjiang.

For strategic, economic, commercial, demographic and political reasons Xinjiang represents an existential issue for China. But despite throwing lots of money at the region and in the past using the iron fist it has failed to win over the Muslims in the region. Whilst the Western media have only now caught onto what China is doing, Beijing’s tactics follow in the footsteps of the West who have similar strategies to deal with their Muslim populations, who they have long struggled to integrate. These tactics have failed in the West and will in all likelihood fail in China. The daunting issue for China’s leaders is its economic and political future runs through a region populated by Muslims, who Beijing has been fighting for over a century.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/July_2009_Ürümqi_riots

[4] https://www.powermag.com/energy-industry-xinjiang-china-potential-problems-solutions-web/

One comment

Hassan

5th September 2022 at 8:38 am

Amazing article. loved it