The project to unite Europe began in earnest after WW2, but in the 21st century it is struggling for survival. The European Union (EU) was created due to the history of Europe, especially its history of war. But today the forces of nationalism, which the union was created to solve, has reared its ugly head and is pulling the union apart at the seams

Europe’s long history of war is what a union of Europe was attempting to solve. Europe’s constant wars had ravaged the continent. Before the emergence of the nation state and nationalism in Europe the Christian Church dominated the continents political landscape. The church’s corruption and the fact that the bible only dealt with limited matters led to constant conflict, leading to religious wars in 1600, which came to be known as the reformation. Over a 31-year period (1914-1945), both World Wars took place in Europe and led to unprecedented slaughter.

The emergence of Germany in 1871 drove it to conquer large chunks of Europe and challenge the British Empire. When WW1 ended in 1918, 20 million people had perished, due to trench warfare and chemical weapons. In 1939 Hitler attempted to conquer Europe and 60 million people perished. Even prior to the world wars Napoleon tried to conquer Europe from 1803 – 1815 in the Napoleonic wars, where over 3 million people perished.

Origins

The wars that had ravaged Europe needed a solution and this was where a union in Europe first emerged. It was believed Europe could overcome nationalism through creating a structure in which Europe act as a union of states. In 1950 the French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman proposed a community to integrate the coal and steel industries of Europe – two elements necessary to make weapons for war. In the text of the treaty he laid out the reasons for a European Union: “a first step in the federation of Europe, starting with the aim of eliminating the possibility of further wars between its member states by means of pooling the national heavy industries.” France, Italy, Belgium, Netherlands, West Germany and Luxembourg signed the Treaty of Paris in 1951, creating the European Coal and Steel Community. This set in motions six decades of integration within Europe. The assumption was that whoever would join the union would cede national sovereignty to institutions within the EU managed by technocrats.

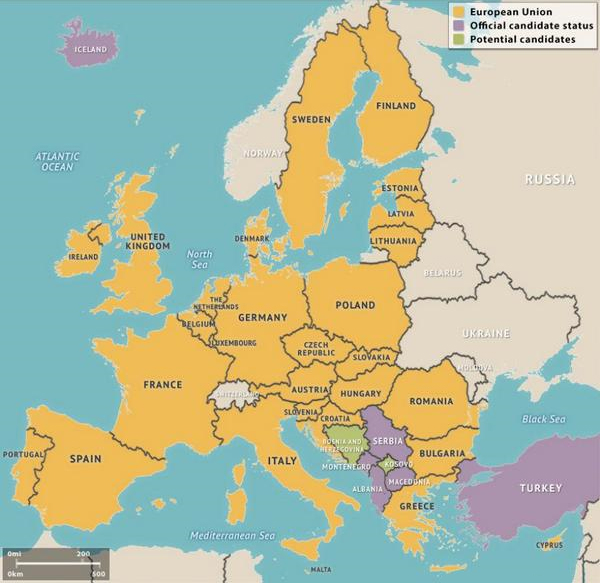

In the intervening years the EU has grown in size by the accession of new member states, and in power by the addition of policy areas to its remit. The Maastricht Treaty established the European Union under its current name in 1993. The most recent amendment to the constitutional basis of the EU, the Treaty of Lisbon, came into force in 2009. The eurozone are those EU member states who surrendered their monetary policy to the European Central Bank (ECB). The 10 EU members such as the UK and Denmark who did not join the eurozone expressly negotiated clauses into existing treaties that granted them legal exemption from ever joining the eurozone. So today the European Union – the EU is an economic and political union, which today consists of 28 member states. The Eurozone on the other hand are 17 of the 28 EU member states who took the union a step further and adopted the Euro as the single currency amongst them.

The EU attempted to overcome centuries of hostile history through a political and economic union. The EU emerged with the goal of creating a system of interdependency in which war in Europe was impossible. Given European history, this was an extraordinarily ambitious project, as war and Europe have gone hand in hand. The idea was that with Germany intimately linked to France, the possibility of significant European conflict could be managed. Underpinning this idea was the concept that the problem of Europe was the problem of nationalism. Unless Europe’s nationalisms were tamed, war would break out. The European Union tried to solve the problem by retaining both national identity and national regimes. Simultaneously, a broader European identity was conceived based on a set of principles, and above all, on the idea of a single European economy binding together disparate nations. The reasoning was that if the European Union provided the foundation for European prosperity, then the continued existence of nations in Europe would not challenge the European Union.

Practically the union created a Common Market where the free movement of labour, goods, services and capital would take place without limitations in Europe. Tariffs would be equalized within the union over time, making trade within the union as if the continent was one nation. The union’s most controversial aspect has been the elimination of border controls within Europe, so people could move and work freely in Europe and for the security of the union a European defence force was proposed.

Crisis

The EU attempted to overcome centuries of hostile history through a political and economic union. The EU emerged with the goal of creating a system of interdependency in which war in Europe was impossible. Given European history, this was an extraordinarily ambitious project, as war and Europe have gone hand in hand

But the Sovereign debt crisis challenged every aspect of the European Union and has brought the spectre of nationalism back to the surface. The principle of the free movement of people, one of the pillars of the EU was enshrined in the Schengen Treaty where internal border controls were eliminated, whilst external borders were reinforced. Today aside from the UK and Ireland, 26 of the EU nations signed the agreement. It also includes nations such as Switzerland, Norway, Iceland and Romania and Bulgaria, when they were candidate nations. Overtime this treaty became the most visible symbols of the EU. But the chaos in the Middle East generated a flow of refugees towards Europe, especially from Syria. Numerous refugees made the long journey through Greece and the Balkans in an attempt to get to Germany. The German initial message of welcome quickly turned to ‘no more welcome.’ But the influx of so many refuges has led to problems within and between EU member states. This has led to some nations, such as Slovenia, building fences to stem the flow of refugees, directly in contravention of the Schengen Treaty. Some nations are thinking about post Schengen. In 2015 the Dutch government discussed plans to create a smaller version which would only include, Holland, Belgium, Luxemburg Germany and Austria. These countries share cultural links and were the Holy Roman Empire in the late 18th century.

The condition of Europe today has shown that as the economic crisis reached its peak, prosperity just exposed the divisions between north and south of Europe and the fact that nationalism is embedded in every negotiation.

The fundamental problem is the EU never really solved nationalism, which has been its curse. Merely creating an economic bloc does not do away with centuries of differences. The EU in fact just institutionalised nationalism and tried to make it more manageable, so whilst Europe has not been in a large scale conflict since WW2, nationalism is everywhere within the EU. The European Union has today expanded well beyond its original founder states. Consensus on how far enlargement should go and how deep integration should be continues to plague the union. Member states are reluctant to relinquish their sovereignty to bureaucrats in Brussels as nationalism between member states is rife within the union. It is these factors that led to the UK to vote to leave the EU, the first nation in the blocks history to do so, opening the door to the blocs potential demise.

It is unlikely the EU will survive in its current form. Many also argue that there is a good chance the EU will not survive at all. Talks of a two tier EU, one with the stronger northern nations and another with the weaker Southern nations. The reality is there is already a two-tier Eurozone just as there is a two tier European Union. To a large extent the problems the Eurozone faces is because of the economic divergence between the top and bottom tiers who are forcibly bound together by the single currency. The only thing really holding the union together is Germany, who benefits immensely from the union, but there will be nothing Germany can do if the forces of nationalism lead to another war on the continent.

After the EU

Europe has always been a continent with so many barriers and differences, be they linguistic, geographical, ethnic and even genetic. With over a millennia of wars, it kept written records of them, informing each generation of all the times their forebears were wronged. Over the centuries, great empires have risen and fallen, leaving behind distinct groups of people with different histories, languages and cultures.

There are certain fixed, underlying truths that will outlast the EU in its current form. One can predict which countries will emerge from a weakened or collapsed EU with close ties, and which are likely to drift apart in pursuit of their own interests once they are freed from the binding force of the European Union and its integrationist ideals.

The fundamental problem is the EU never really solved nationalism, which has been its curse. Merely creating an economic bloc does not do away with centuries of differences. The EU in fact just institutionalized nationalism and tried to make it more manageable

The Benelux region – Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg have long played a key role in European politics, situated as they are between Europe’s two great powers, France and Germany. Indeed, it was in the Benelux region that the European project began. It is likely the Benelux, France and Germany will be motivated to continue their integration efforts. Caught between two economic powers, the Benelux will want to secure their friendship.

Germany – All post EU scenarios will most likely see Germany maintain its influential position due to its economic relationships with all the countries of the continent. The past two decades has seen Germany assemble a trade coleuses. Germany is the number one export destination for 14 of its 27 EU peers, and the top source of imports for 15 of them. European Union or not, the players in this network will all be highly motivated to keep it running.

Central and Eastern Europe – This geographic divergence will divide Central and Eastern Europe into two groups, one focused on trade and the other on security. The Central Europeans (the Czechs, Hungarians, Romanians, Bulgarians and Slovaks) will be wary of antagonising Russia. The Carpathians, though a barrier, are not insuperable. And yet these countries, sheltered by the mountains, will also be free to focus much of their energy toward pursuing continued prosperity through trade with the core. Poland and the Baltics, by contrast, will not have the luxury of focusing primarily on their own enrichment. With Russia’s presence looming, these countries will be bound closely together, focusing their energies on defence pacts and alliances but the identity of this bloc will centre on resisting the Russian threat.

Scandinavia – In the north, Scandinavia will form its own bloc. Its members have a history of shared empires, free trade, freedom of movement agreements and a failed currency union; they are natural partners. The Nordic Council as an institution has been dormant since the rise of the EU, but it already exists to aid their international governance.