By Imran Khan

On April 23rd 2025, the day after the Pahalgam attack in Indian held Kashmir, India officially suspended the Indus Water treaty citing national security concerns and alleging Pakistan’s support of state-sponsored terrorism. The 1960 Indus Water Treaty is the only agreement between both nations that has managed to survive the contentious relationship. Despite India and Pakistan having fought three major wars and numerous other military skirmishes, conflicts, and engagements since their independence in 1947, this was the only agreement that had survived the test of time. But India has wanted to reform the treaty for some time and has been dissatisfied with certain aspects of the treaty due to changing dynamics. The suspension of the treaty now places Pakistan in a precarious geopolitical position.

The Gateway

In the 3rd millennium BC the Indus Valley Civilisation emerged and its economy, society and way of life came to depend on the Indus River. The Indus River came to the knowledge of the Western world when King Darius of Persia sent his Greek subject Scylax of Caryanda to explore the river, c. 515 BC. The Indus river has been viewed as the gateway to the Indian subcontinent by numerous civilisations throughout history.

It was crossed by the invading armies of Alexander the Great who then joined it to the Hellenic world. Over several centuries Muslim armies of Muhammad ibn al-Qasim, Mahmud of Ghazni, Muhammad of Ghor, Timur and Babur crossed the river to conquer Sindh and Punjab, cementing it as the gateway to the Indian subcontinent. Even the word India is derived from the Indus River

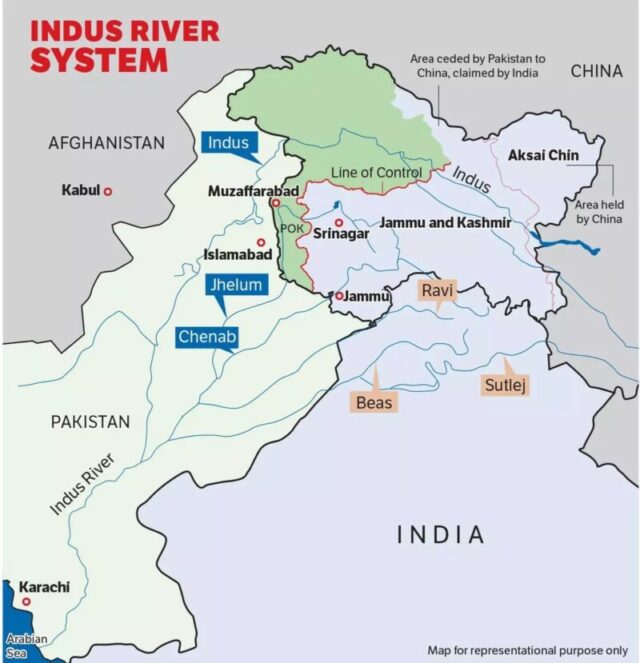

The waters of the Indus water basin begin in the Himalayan mountains and travel through Himachal Pradesh and combined Kashmir. They flow through Punjab and Sindh before emptying into the Arabian Sea south of Karachi and Kori Creek in Gujarat. The 2,000 miles of river has been essential for social, economic, and cultural life since ancient times.

During British rule over India the Empire constructed extensive irrigation systems in eastern and western Punjab. Central and eastern Punjab had a lush ecosystem with plenty of rain, while western Punjab was dry and was mostly barren. Under British rule, the fertile areas in central and eastern Punjab were used for commercial farming, while western Punjab remained less developed. After 1857, the British expanded irrigation in western Punjab. Canal colonies in western Punjab were built leading to the largest irrigation canal system in the world at the time. This turned western Punjab into a key area for colonial farming, producing wheat, cotton, and sugarcane.

When the British partitioned the Indian subcontinent it was based on religion and didn’t take into account the geography and this immediately created a conflict over the waters of the Indus basin. The newly formed states were at odds over how to share and manage what was essentially a cohesive and unitary network of irrigation. The British built numerous tributaries and irrigation networks in Punjab, which after partition saw some river systems end up in Pakistan and some in India as the Radcliffe line split Punjab into two. India retained the headwater infrastructure, while Pakistan got the extensive canal system. This uneven distribution led to conflicts over shared water resources.

In April 1948, the water dispute quickly escalated when India blocked the Ferozepur headworks, temporarily cutting off supplies to Pakistan’s Dipalpur and Upper Bari Doab Canals. India argued it had ownership rights, while Pakistan claimed rights based on previous use. International water law didn’t exist at the time, as we have now, but India and Pakistan reached an agreement to avoid war, but there was no agreement on how to settle the dispute.

Sharing the Indus

After ten years of complicated negotiations led by the World Bank, India’s Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Pakistan’s military leader Ayub Khan signed the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) in Karachi in 1960. The World Bank acted as the treaty’s guarantor and provided a neutral expert and chairperson for conflict resolution. A joint Permanent Indus Commission was set up to handle issues and maintain the agreement between the two countries.

The IWT resolved the water conflict by dividing the rivers between India and Pakistan instead of equally sharing water. Pakistan got control of the western rivers—Jhelum, Chenab, and the Indus—while India was given the eastern rivers—Sutlej, Ravi, and Beas. The treaty created a clear separation, similar to the partition of India, leading to division rather than collaboration over the Indus River system. It treated the waters as a resource to be divided rather than shared use.

Under the treaty, India got 30% of the water from the Indus River system, while Pakistan was to receive 70%. The World Bank considers the treaty one of the most successful agreements for resolving water disputes.

Changing Water Dynamics

For Pakistan the Indus river plays a central role in the nation’s agriculture. The river supplies more than 16 million hectares of farmland that produces wheat, rice, and sugarcane—the mainstay of food security for a population now exceeding 240 million. Additionally, the river accounts for nearly 30% of Pakistan’s energy through hydroelectric generation. It also serves as the main water source for agriculture, domestic use, and industry. The Indus is indispensable to Pakistan’s economy and supports the livelihoods of millions across the country.

The Indus River, along with tributaries like the Sutlej, Ravi, and Beas, are also indispensable for India, especially in the states of Punjab and Haryana. It irrigates around 3 million hectares of farmland, supporting the cultivation of crucial crops such as wheat and rice, which are vital for the country’s food security. Hydroelectric projects on these rivers significantly contribute to India’s energy supply, powering millions of homes and industries. Despite accessing only 30% of the system’s water, the Indus system is crucial in meeting the agricultural and energy demands of northern India.

Pakistan and India have been at war on three occasions alongside numerous skirmishes, but despite this, the treaty has surprisingly held and remained intact. Though the Indus Waters Treaty has successfully mitigated the threat of India-Pakistan water conflict for decades, disagreements have arisen since the turn of the century as both countries’ populations and demand for energy and water have grown.

India has argued that the eastern rivers it controls make-up only 20% of the total water of the Indus River system, which alongside significant environmental, demographic and economic changes that have transpired since the treaty’s signing in 1960, warrants a renegotiation of the treaty’s terms.

Whilst Pakistan’s location downstream has made it sensitive to India’s growing use of the western rivers, particularly for hydroelectric projects, Pakistan claims some of these projects violate India’s treaty obligations to allow the western rivers to flow unimpeded. Islamabad has used these arguments and the treaty’s dispute mechanisms to help stall India’s hydropower projects. India has sent Pakistan four formal requests to reassess the treaty’s obligations, therefore even before India’s formal departure, problems were brewing.

Following the 2016 attack on the Uri Army camp by Jaish-e-Mohammad, Prime Minister Narendra Modi began associating the Indus Water Treaty with national security concerns. This shift in policy sharpened domestic opposition and sparked renewed calls to renegotiate the treaty. In a meeting after the Uri attacks, Narendra Modi stated, “Blood and water cannot flow simultaneously.”

Pakistan’s failure to prepare for this day, which was very likely due to the contentious relationship both nations have, has now pushed it into a corner, with very few viable options

India Strikes

It remains to be seen if India will follow through on its revocation of the Indus Water Treaty. But this has been the direction India has been going for the last two decades and so Pakistan faces a strategic dilemma that it will need to deal with.

The downstream consequences for Pakistan would be severe. The Indus River system is vital to Pakistan as it provides about 80% of the water for its irrigated agriculture. Around 40% of Pakistan’s workforce is engaged in agriculture, any significant disruption in water supply will threaten food security and economic stability.

Economically, Pakistan’s GDP is heavily dependent on agriculture, which accounts for over 20% of its total output. Changes in water availability due to modifications in the treaty will reduce crop yields, affecting both food supply and export revenues. Such disruptions would further aggravate existing economic challenges, including inflation and unemployment.

India can build dams in order to divert the waters from the Indus. Although this will take anywhere between 5 years to a decade, Pakistan in the medium to long term will need to find a solution. Despite the fact that Pakistan and India have long had animosity, successive Pakistani administrations have not used the 6 decades since the treaty signing to search for alternative solutions. Pakistan has not searched for a technological solution nor made the investment to search for alternative water sources severely limiting Pakistan now which has its back against the wall.

Pakistan could pursue a military solution by unifying with Kashmir

Any diplomatic solution through negotiations may leave Pakistan in a worse position as India wants to increase its share of the waters. Pakistan could pursue a military solution by unifying with Kashmir. This was Pakistan’s long-term policy and saw it support, fund and train armed groups to carry out an insurgency against India in order to bleed it to death. But after 9/11 and General Musharraf’s unstinting support to the US war on terror, Pakistan abandoned such groups, seized their assets and imprisoned their leaders. Musharraf even pursued normalisation with India. Since 9/11 Pakistan’s ruling elite effectively abandoned Kashmir and now the country finds itself in a worse dilemma.

Whilst many were surprised at Pakistan’s performance in the recent war as well as India’s lack of performance, the battle is really one side of the war. Pakistan may have won this recent battle, but it may lose the war with India’s revocation of the Indus Water Treaty. India on the other hand, may have lost a number of jets and lost the battle, but it may win the war by abandoning the strategic treaty. Pakistan’s failure to prepare for this day, which was very likely due to the contentious relationship both nations have, has now pushed it into a corner, with very few viable options.