By Abdullah as Siddiq

World leaders have gathered in Baku, Azerbaijan for the most important meeting on climate change – COP29. A range of issues are on the agenda from how to limit long-term global temperature rise and limit fossil use. With the return of Donald Trump to the White House the future of COP is also in question. Ever since global leaders gathered in Stockholm back in 1972 to first discuss the impact human lifestyles were having on the climate, numerous agreements and commitments have been agreed but geopolitics has got in the way of implementation. In this deep dive we look at the origins of the climate agenda and the various interests that have tried to push and pull it in different directions.

During the 1950s it became clear that the natural ecosystems in North America and Europe, the rivers, lakes, oceans and forests, were adversely affected by the industrial boom that followed the second world war. Newspapers regularly reported about events previously unheard of, such as masses of dead fish floating on the surface of lakes and oceans, birds falling dead from the sky following aerial release of mosquito repellant, forests dying from toxic chemicals trapped in rainwater, and even “burning rivers” caused by dumped oil products catching fire.

One naturalist in the United States realised pollution was causing not only permanent damage to plants and animals, but also humans. Working for the United States’ Fish and Wildlife Service, a governmental agency, Rachel Carson systematically studied the impact of synthetic pesticides on the natural environment, and from there, through the food chain, on humans. In 1962 she published her findings in the book “Silent Spring”. Because Carson’s previous books on nature and wildlife, “The Sea Around Us,” “The Edge of the Sea” and “Under the Sea-Wind”, had all been very popular, “Silent Spring” became a bestseller across the western world. Consequently, the warnings it contained, that human activity was poisoning nature, and that if left unaddressed this would lead to nature poisoning life, became prominent in the public debate.

After Carson’s “Silent Spring” a number of other books further raised public awareness of pollution, the environmental damage it caused, and its consequences on life. In the United States Stewart Udall published “The Quiet Crisis” in 1963. In France, Jean Dorst published “Before Nature Dies” in 1965. In Sweden, Rolf Edberg published “On the Shred of a Cloud” in 1966, and Hans Palmstierna “Plunder, Famine, Poisoning” in 1967. In the United Kingdom, Max Nicholson published “The Environmental Revolution” in 1970. Together, these publications drove a flourishing of environmental movements across North America and Europe during the 1960s, which put pressure on governments to act against pollution and the environmental damage it causes.[1]

The Environment Arrives on the Geopolitical Stage

Rachel Carson found a strong supporter in American president John F. Kennedy. Kennedy not only studied “Silent Spring”, he also supported Carson to spread her message, personally intervened to protect her against efforts by industrialists to smear her, and arranged for her to appear before the United States Senate in June 1963 to give testimony on the subject of pollution and environmental damage.[2] Her testimony deeply influenced political discourse in the United States, and as a result, over the 1960s and 1970s the United States enacted a range of environmental laws and regulations, including the Clean Air Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and the Endangered Species Act.[3]

Over in Europe, the government of Sweden decided to place the general public’s concerns about pollution and environment damage on the international political agenda. In 1967 it proposed to organise a United Nations conference on the environment, to drive discussion at the global level about pollution and environmental damage. Most of the countries in North America and Europe, including those associated with the Soviet Union, decided to support the initiative. The exceptions were France and the United Kingdom, who worried that the conference would be used by countries in the developing world to demand financial support for protecting the environment from former colonial powers. The countries of the developing world, meanwhile, feared that the conference proposed by Sweden would be used by the countries in the developed world to establish roadblocks on their way to economic prosperity. In effect, they feared that the former colonial powers would use environmental issues as an excuse to restrict their development.

The countries of the developing world, meanwhile, feared that the conference proposed by Sweden would be used by the countries in the developed world to establish roadblocks on their way to economic prosperity

Most importantly, however, Sweden’s proposal found strong support in the United States. On the one hand because the pollution and environment damage had already become a prominent political issue there. On the other hand, because of political expediency. During the 1960s the United States experienced domestic resistance against its involvement in the Vietnam War. Senator Gaylord Nelson from Wisconsin, for example, was so concerned about these protests that he decided to support the environmental movement in an attempt to redirect people’s attention away from the anti-Vietnam War protest movement.[4] For this reason, politicians in the United States such as Senator Nelson considered the Swedish proposal to focus international attention on the environment a useful redirection of public attention.

Because of this support, in 1969 the United Nations agreed to a conference on the subject of the environment. It decided this conference was to be held in the capital of Sweden, Stockholm, in 1972. The conference was to be named the “United Nations Conference on the Human Environment” and Canadian Maurice Strong was appointed as Secretary General of the conference. In this role, Strong, a prominent businessman in Canada’s oil and gas industry[5], was responsible for the overall organisation of the conference.

Strong accepted an offer of support from another businessman in the oil and gas industry, Robert Anderson of the Atlantic Richfield Company[6], to help him organise the conference. Anderson’s company was involved in the extraction of oil from Prudhoe Bay in Alaska, the United States. The pipeline to transport this oil to markets in Canada and the United States had been delayed, and made more costly, by environmentalists who raised its impacts on the environment as an issue. In response, in 1971 Anderson had set up the International Institute for Environmental Affairs (IIEA) to better understand how the environmental movement affected his industry. Anderson made the IIEA available to Strong. Strong also called in the support of Barbara Ward, who at the time was one of the world’s leading development experts.[7]

politicians in the United States such as Senator Nelson considered the Swedish proposal to focus international attention on the environment a useful redirection of public attention

To manage the suspicions of the countries in the developing world that the Stockholm Conference was a ploy by the countries of the developed world to hold them back in their development, which made some countries in the developing world consider not attending the Stockholm Conference, in 1971 Strong and his team brought representatives from the countries in the developing world together in Founex, Switzerland, for a preparatory convention. There, Strong framed the issue of pollution and environmental damage as one that is common but different for the developed and the developing world. For countries in the developed world, Strong and his team argued, pollution and environmental damage were the result of economic development. For them, industrialization had led to pollution. But in the countries of the developing world, Strong and his team argued, pollution and environmental damage were primarily due to a lack of development. For example, the absence of proper sanitation systems was causing water pollution in the countries of the developing world. Based on this, Strong argued that the Stockholm Conference would be about supporting the countries of the developing world. It would help them to address their poverty-linked pollution and environmental damage, and to avoid the development-linked pollution and environment damage experienced by the countries of the developed world. The Stockholm Conference would enable the countries of the developing world to discuss with the countries of the developed world mechanisms through which the latter would support the prior to achieve “sustainable development”. Based on this narrative, most countries in the developing world agreed to lend their support to the Stockholm Conference, and thereby for the conference’s vision of linking development with environmental protection.[8]

With support from the developing world assured, Strong, Ward and the team of the IIEA started work on organising the actual Stockholm Conference of 1972. Strong brought Ward in contact with a French scientist named Rene Dubos and instructed the two to write a book based on the Founex report that could become the intellectual underpinning of the conference. Upon completion this book was named “Only One Earth”. It set out the fundamental premises of the Stockholm Conference, namely that:

1) The developed world was responsible for the pollution and environmental damage caused by its development, and thus responsible for solving it;

2) That the developing world was responsible for the pollution and environmental damage caused by its lack of development, and thus responsible for solving it;

3) That the developing world would pursue development in a manner that would avoid the pollution and environmental damage experienced by the developed world; and

4) That the developed world would offer “new and additional resources” to the developing world, to help them achieve this more sustainable development.

This principle established by the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment of 1972, known as the principle of sustainable development, would form the basis of all later international conversations on the environment.[9]

The Rio Earth Summit and Climate Change

Fifteen years after the Stockholm Conference, in 1987, the United Nations’ World Commission on Environment and Development (UNWCED) released a report that further supported the sustainable development principle established by the Stockholm Conference. Officially entitled “Our Common Future”, but often referred to as the Brundtland Report after the Prime Minister of Norway Gro Harlem Brundtland who led the team that developed it, the report argued that the world had failed to make the progress called for during the Stockholm Conference, but that it was nevertheless possible to have economic growth, and to eliminate poverty, in an environmentally sustainable manner.[10]

Based on this report, in 1992 a second United Nations conference on the environment was organised, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. This conference was again organised by Maurice Strong with support from the IIEA, which had by then renamed itself as the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED). Strong and the IIED had also been among the key contributors to “Our Common Future”, which formed the intellectual underpinning of the conference, similar to “Only One Earth” at the Stockholm Conference.[11] This 1992 conference, officially named the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development but popularly known as the Rio Earth Summit, aimed at developing a clear agenda for global collaboration on developmental and environmental issues for the 21st century.[12]

The discussions on the subject resulted in an agreement named Agenda 21, which set out what countries should do, and how they should collaborate, to deliver sustainable development.[13] Building on the Stockholm Conference, the Rio Earth Summit for the first time calculated the investments that would be necessary to achieve this sustainable development globally. It came up with the number of $600 billion annually, of which $125 billion should be in the form of financial support from the developed world to the developing world. However, no agreement was reached on actual financial support from the developed world for the developing world.

The Rio Earth Summit also differed from the Stockholm Conference in a number of ways. Most importantly, the Rio Earth Summit was the first to raise greenhouse gas emissions to the forefront of the environmental debate. This was in no small part due to testimonies by NASA scientist Dr. James Hansen in front of the United States Congress. During his testimonies Dr. Hansen made three claims that captured the world’s attention. First, that he was 99% sure the earth was warming. Second, he could say with a high degree of confidence that the warming was due to an increase in greenhouse gases in the atmosphere due to human activity. And third, that because of global warming, events like droughts would increase noticeably during the 1990s and beyond.[14] To combat the climate changing impact of greenhouse gases, the participants in Rio’s Earth Summit agreed to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), to provide a platform for discussion on combating “…dangerous human interference with the climate system”, through stabilising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.

Rio also differed from Stockholm in that it formalised the concept of “common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR)”. In the run up to the Stockholm Conference the agreement between the developed and developing world reached in Founex, Switzerland, said that both were causing pollution and environmental damage, just in different ways. The Rio Earth Summit formalised this into the concept of “common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR)”, which was commonly understood as meaning that the countries of the developed world have a bigger responsibility for undoing pollution and environmental damage than the countries of the developing world. And thus, that while all countries should play their part to undo some of this damage and prevent further damage, the countries of the developed world should do more.[15]

The United States blocked efforts to adopt specific targets or timelines for environmental protection at the Rio Earth Summit. It proposed using trade liberalisation to promote “free market solutions” for the world’s environmental problems, rather than government regulation.[16] And it suggested the use of trade measures such as tariffs and import bans, to punish countries if they were deemed to show insufficient support for environmental goals.[17]

The Era of Climate Change Mitigation

Since 1995 the UNFCCC has organised annual conferences dedicated to climate change mitigation, so-called “Conference of the Parties (COP) meetings”, to assess progress in dealing with climate change and agreeing on future climate action. Based on the CBDR principle, the outcome of the first COP, commonly referred to as COP1 which was held in Berlin, Germany, was that countries of the developed world should take the first step in stabilising greenhouse gases, while countries of the developing world should follow suit at a later stage.

This led to the Kyoto Protocol, which was developed during COP3 in Kyoto, Japan, in 1997. The Kyoto Protocol was a proposal that over the period 2008 to 2020, countries from the developed world, referred to as Annex I countries, should achieve a reduction in their greenhouse gas emissions compared to their 1990 emission levels. And, that the countries of the developed world should offer financial and technological support to the countries of the developing world, to help them manage their emissions. All members of the UNFCCC signed the Kyoto Protocol. However, the United States Congress refused to ratify it, because the United States’ negotiators had not been able to insert in the Protocol a binding obligation for countries in the developing world, in particular China, to also reduce their emissions.[18] Primarily because of this move by the United States, none of the countries in the developed world undertook concrete action to abide by their commitments in the Kyoto Protocol, neither their emissions reduction commitment nor their commitment to support countries in the developing world.[19]

In 2009, during COP15 in Copenhagen, Denmark, an agreement was reached regarding the amount of financial support which the countries of the developing world should receive from the countries of the developed world. Promised since the original Stockholm Conference of 1972, and quantified at Rio in 1987, in Copenhagen the developed countries agreed to provide $30 billion over the period 2010 to 2012, and $100 billion per year starting 2020.[20]

In 2010, at COP16 in Cancun, Mexico, an agreement was reached as to the target of the climate change mitigation efforts of the UNFCCC and COP. The participating countries agreed to target a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions that would limit climate change to a maximum of 2 degrees centigrade above pre-industrial levels, by the end of the 21st century.[21]

During COP21, held in 2015 in Paris, France, the members of the UNFCCC signed the Paris Agreement which did away with the CBDR principle at the core of the UNFCCC. Instead, at the demand of the United States they agreed to adopt the principle that all countries, irrespective of whether they are developed or developing, should support efforts to “…limit global warming to well below 2, preferably to 1.5 degrees centigrade, compared to pre-industrial levels”, and therefore should “…aim to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible, to achieve a climate neutral world by mid-century”.[22] To make the developing world accept this highly significant change, the Paris Agreement included a framework to organise financial and technological support from the countries in the developed world to the countries in the developing world – something that, although promised at the 1972 Stockholm Conference, quantified during the Rio Earth Summit of 1987, and agreed upon at the 2009 COP15 in Copenhagen, had never materialised. In short, the countries of the developed world (again) promised to provide the developing countries a minimum of $100 billion in financial support per year, but this time in exchange for the countries of the developing world agreeing to being equally obligated to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions.[23] In the end, this promise got China to sign the agreement, promising that it would achieve peaking of its greenhouse gas emissions around 2030.[24]

the countries of the developed world (again) promised to provide the developing countries a minimum of $100 billion in financial support per year, but this time in exchange for the countries of the developing world agreeing to being equally obligated to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions

At the last COP meeting, COP26 which was held during 2021 in Glasgow, Great Britain, built on the Paris Agreement. Ahead of COP26, analysis showed that if all announced pledges were implemented in full and on time, this would result in a 2.1 degrees centigrade increase in average global temperatures by the end of the century.[25] COP26 therefore had three overarching goals. The first was to ensure commitments from all members to reduce the emissions in such a way that the targets of the Paris Agreement remained achievable. The second, to develop global collaboration to support communities that are affected by climate change, because the efforts to mitigate climate change were behind the schedule of the Paris Agreement. And the third, to prepare the promised $100 billion in financial support for developing countries.[26]

A Criticism of the Climate Change agenda

The global collaboration to address pollution and environmental damage has changed dramatically since the 1972 United Nations’ Stockholm Conference on the Environment. As to the scope of this collaboration, originally it was very broadly defined, covering a wide range of environmental problems. Over time, however, the scope has narrowed, and today it is largely focused on addressing climate change, caused by the emission of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide (CO2). As to the basis for this collaboration, originally it was defined as “common by differentiated”. The problem of pollution and environmental damage was considered “common” for the countries of the developed and the developing world, but the efforts expected from both to address this problem were differentiated, with the countries of the developed world promising to take the lead and to support the countries of the developing world to enable them to follow. Over time however, this basis for collaboration too has changed. Today, all countries are expected to put in an equal effort, as the countries of the developed world have made their efforts, and their support for the countries of the developing world, conditional upon the countries of the developing world doing the same. These changes, and the current agenda to mitigate climate change it has resulted in, are fundamentally unfair.

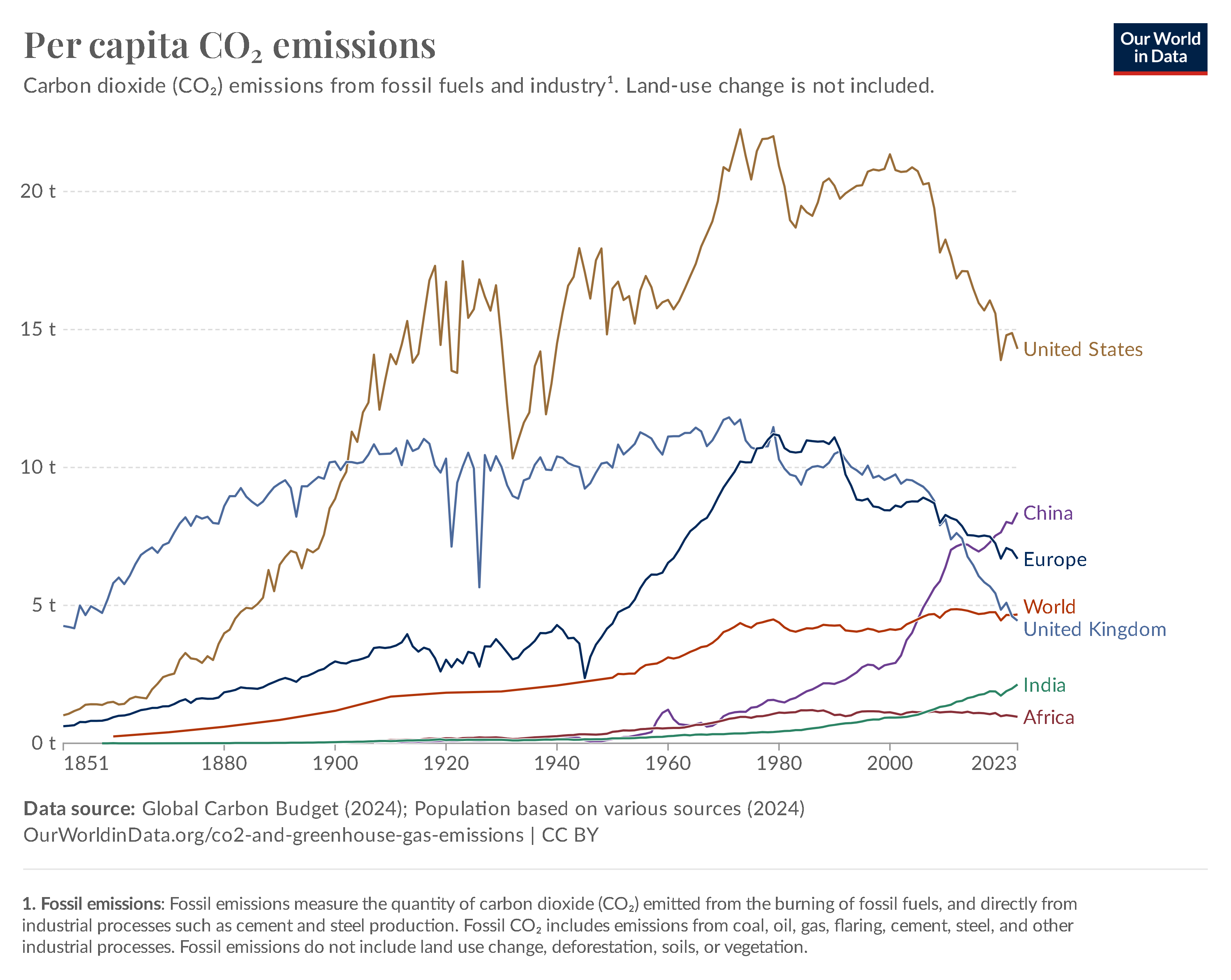

Since 1751, considered the start of the industrial revolution, the world has emitted over 1.5 trillion tons of greenhouse gases. The 28 countries of the European Union (including Great Britain) emitted the largest part of this, namely 32%. The United States is responsible for 25% of these historical emissions, while China is responsible for 13% and Russia for 6%. Combined, the emissions of the countries in the developing world such as India, Brazil, Indonesia, and the remainder of Asia and Africa, make up less than 10% of total historic emissions.[27] This means that the responsibility for the excess amount of greenhouse gases currently in the atmosphere, and the climate change that is resulting from it, lies primarily with the countries of the developed world. Consequently, fairness requires them to address the problem, because they are the ones who created it.

Given that access to abundant cheap energy is a critical requirement for development and elevating people from poverty[28], it can even be argued that fairness requires the countries of the developing world to remove some of their historic emissions from the atmosphere, just to create room for additional emissions from the developing countries. This is because the countries of the developed world achieved their status through unhindered combustion of coal, oil, and gas, together with large-scale deforestation. This enabled their industries to become competitive on international markets, through which the wealth was created that pulled the populations of these countries out of poverty. This has created the dilemma of, on the one hand, climate change due to excessive amounts of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and, on the other hand, continued poverty in the developing world. The only fair way out of this dilemma is for the developed countries to remove part of their historic emissions from the atmosphere, such that room is created for the developing countries to develop in an unhindered manner and they can pull their populations out of poverty as well. Anything short of that limits the ability of the countries of the developing world to develop access to abundant cheap energy, which effectively puts up a barrier to them elevating the poor in their countries out of poverty.[29]

The Hypocrisy of Climate Change Mitigation

This agenda was forced upon the countries of the developing world by the countries in the developed world, when the countries of the developed world made their efforts and support for the countries of the developing world conditional upon the countries of the developing world committing to the same effort. This is hypocritical by the countries of the developed world because not only are they responsible for the greenhouse gases built up in the atmosphere since 1751, they remain primarily responsible for the bulk of greenhouse gas emissions even today. In 2015, the average American emitted some 16 tons of greenhouse gases per person per year. The average European emitted 7 tons, which is roughly the same as the average Chinese. The average Indian, meanwhile, emitted less than 2 tons per year. The people in the rest of the developing world emit significantly less still. The average for sub-Saharan Africa was less than 1 ton per year, just 5% of the emissions of the average American.[30] On a lifestyle-basis the gap between the countries of the developed world and the countries of the developing world is even larger, because a significant amount of the emissions in the countries of the developing world are associated with the manufacturing of goods that are exported for consumption to the countries of the developed world. On this lifestyle-basis, also known as consumption-based emissions, the average American emitted not 16 but 17 tons of greenhouse gases every year, and the average European not 7 but 8 tons. The emissions of the average Chinese, meanwhile, drop from 7 to 6 tons; those of the average Indian drop from 1.7 to 1.6; and those of Africa drop from 0.8 to 0.6.[31]

This means that if, according to the current agenda to mitigate climate change, from the current point onward all countries reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases, such that by a certain point in the future all countries will have reached zero emissions of greenhouse gases, then effectively the countries of the developed world will not only have led the world in past emissions, but also in future emissions. This is because if, for example, the world would agree to reduce emissions by 4% from the current level every year, such that 25 years from now emissions will have dropped to zero, then, because they are starting from much higher levels of emissions, the countries of the developed world will continue to emit more greenhouse gases than the countries of the developing world, every year, until the year world emissions reach zero! In other words, the current agenda to mitigate climate change means that the worst polluters are allowed to continue to remain the worst polluters, until all pollution has stopped.

Until the countries of the developed world clean up their act, and bring their emissions share in historic emissions down to the level of the countries in the developing world, it is nothing short of hypocrisy for the countries of the developed world to demand from the countries of the developing world that they put in an “equal effort” to reduce emissions.

The hypocrisy of the current agenda to mitigate climate change also shows in the countries of the developed world, who pushed for this agenda, not living up to their promise of support for the countries of the developing world. As mentioned, this promise of support is as old as the global collaboration to address the pollution and environmental damage that has resulted from economic development. This promise was first made by the countries of the developed world to the countries of the developing world in the run up to the Stockholm Conference of 1972. It then took almost 40 years, until COP15 in Copenhagen, 2009, for this promise to translate into a concrete offer of $100 billion per year. But, during COP21 in Paris, 2015, this offer was effectively rescinded as the countries of the developing world were forced to accept an emissions reduction obligation before they could receive any financial support. They agreed to this, although this demand from the countries of the developed world was unfair and hypocritical. But nevertheless, the support received by the countries of the developing world has remained significantly below the promised amount. In 2019 it was $80 billion.[32] In 2020 it fell by 5% to $76 billion.[33] The majority of this support, however, is not really support but rather loans that will need to be paid back, with interest. If these loans are removed from the numbers, the remaining amount of real support from the countries of the developed world to the countries of the developing world is just $20 billion annually.[34] Interestingly, the most developed country lived up to its promise the least. Based on the size of its economy and its share in global greenhouse gas emissions, the United States is providing less than half of what would be its fair share of the promised $100 billion.[35]

What makes this broken promise all the worse is the fact that $100 billion annually is not nearly enough. According to the World Bank, the countries of the developing world will need at least $70 billion to $100 billion per year just to adapt to the consequences of climate change.[36] The UN Environment Program (UNEP) estimates that these adaptation costs alone will be in a range of $140 billion to $300 billion annually by 2030, and $280 billion to $500 billion annually by 2050.[37] To manage the actual reduction in emissions targeted by the Paris Agreement, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that an annual investment of $3 trillion is needed in the energy system alone.[38] This is around 2.5% of the value of the world economy. According to the International Energy Agency, the countries of the developing world require between $2.6 trillion and $4.6 trillion annually to manage both adaptation to climate change and a reduction in their greenhouse gas emissions towards zero,[39] a multitude of the promised but undelivered support from the countries of the developed world.

Interestingly, the most developed country lived up to its promise the least. Based on the size of its economy and its share in global greenhouse gas emissions, the United States is providing less than half of what would be its fair share of the promised $100 billion

The Climate Change agenda and Geopolitics

The changes to the global collaboration to address pollution and environmental damage, which has led to the unfair and hypocritical current agenda under which all countries are expected to deliver an equal effort to mitigate climate change, did not occur by coincidence. As documented, they resulted from conscious political choices, pushed by the leading countries in the developed world, in particular the United States.

In the 1960s the United States was one of the countries that supported efforts to bring the subject of pollution and environmental damage to the global political stage. During the 1980s and 1990s the United States was the country which directed the attention of this global political stage to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. And throughout the 21st century the United States has led the effort to move away from the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities for mitigating the problem of climate change, and to move toward the principle that all countries have an equal responsibility.

The United States continues to drive further changes to the agenda.

Firstly, in the run up to the last COP, the COP26 of 2021 which was held in Glasgow, Great Britain, the United States promoted the view that the global collaboration to reduce greenhouse gas emissions should no longer target the upper limit of “…well below 2…” degrees centigrade, as defined by the Paris Agreement of 2015, but rather the lower limit of “…preferably to 1.5…” degrees centigrade suggested by that agreement. “It’s better to make that your target…”, the United States’ lead negotiator, Special Envoy for Climate John Kerry, said on this.[40] This is important because of its implications. Lowering the target means, namely, that whatever countries committed to as part of the Paris Agreement will need to be renegotiated, as those commitments were aligned with 2 degrees but not with 1.5 degrees. In other words, the shift to 1.5 degrees lays the groundwork for new negotiations on commitments.

Secondly, the United States pushed for coal to become the main topic for these negotiations. “Coal is the primary culprit today in warming the planet, and in polluting the air and in creating the intensity of storms that comes with increased moisture that rises from the oceans”, Kerry said. “We have to, all of us, be able to put the deals together that will phase out (…) coal fast”.[41]

Thirdly, this narrative around coal really focuses on future emissions, rather than historic emissions. This makes no sense rationally. It means, namely, that the United States wants the climate change agenda to move even further away from the original principle of common but differentiated responsibilities. This original principle acknowledged the fact that the countries of the developed world are primarily responsible for the current levels of greenhouse gases in the world’s atmosphere. The current principle of equal responsibility does not deny this historical fact, but downplays it, as it calls for all countries to make the same commitment around greenhouse gas emission reductions. The agenda now being called for, however, completely ignores the historical responsibility of the countries of the developed world, as it limits the conversation to the emissions of the future. While this makes no rational sense, it does enable the United States to target the countries that still need significant industrialization, and which use coal to achieve this, with demands for increases in commitments to mitigate climate change. “You have China, India, Russia, Brazil, Mexico, Indonesia, South Africa, a group of countries that are going to have to step up”, Kerry said.[42]

Thereafter, fourthly, the United States made its main allies in Asia, South Korea and Japan, promise they would stop financing coal-based projects internationally. This left China as the only country continuing to do so.[43] The United States then began talking to the countries in the developing world that collaborated with China on coal-based projects, offering them money and other kinds of support if they ended these collaborations and promised to work with the United States and its allies instead. “We’re prepared to help bring finance and technology to the table and work diligently with them”, Kerry said. “Trillions can clearly — and will need to — be invested. (…) We are working out the details of these different options right now. We want to be very specific. None of this should be pie in the sky. It needs to be real and economically viable.”[44] The United States was very clear, however, that this offer of support was not directed to China to help it reduce its usage of coal in order to reduce its emissions. All countries could expect support from the United States, but not China.

This new agenda for the future of the global collaboration to address climate change pushed by the United States is very clearly directed at China. It aims to isolate China as a pariah state, by presenting it to the world as “…the one country that refuses to collaborate for mitigating climate change…”, and thereby as “…the country that is responsible for climate change…” – although in reality the United States has contributed the most to the greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and the lifestyle of the people in the United States is the problem that causes these greenhouse gases to continue to increase.

If China were to respond to this pressure by accepting the demands of the United States, and commit to ending its use of coal, this would severely hinder China’s ability to continue developing its economy. It would then, namely, have to direct significant resources to the task of ending coal usage. At present, China gets 57% of its electricity from coal. Immense investments would then be required to generate electricity from other sources, such as gas, which it would have to import from abroad, nuclear, wind or solar. In addition, coal is used by Chinese industries such as steel, aluminium and petrochemicals. Further immense investment would be required to change this.[45] The coal industry in China also employs over 4 million Chinese.[46] Additionally, coal is used by poorer Chinese households for heating and cooking. An aggressive move away from coal therefore also risks social unrest, unless China prepares further immense investment to support these people who would be severely affected by a move away from coal. Clearly, these investments would constrain China’s ability to spend in other areas, such as the military, education and R&D, or the building of international alliances. This is exactly what the United States wants to see happening, because that would enable it to maintain its position of global hegemon.

This new agenda for the future of the global collaboration to address climate change pushed by the United States is very clearly directed at China. It aims to isolate China as a pariah state

But, if China were to refuse to respond to the pressure created by the manoeuvring of the United States, then the United States’ new agenda for the future of the global collaboration to mitigate climate change will enable the United States to create another problem for China. In this case, the United States could create a “climate club” of countries that are willing to work with the United States on the basis of the new agenda, and agree with the countries of this club to impose tariffs on imports from countries that do not, such as China. This policy suggestion was first articulated by the United States at the time of the Rio Earth Summit. It was brought to the forefront again in Foreign Affairs, back in 2020[47], and reprinted again. [48] In this case, Chinese companies would effectively be cut off from the world’s main consumer markets, the United States and Europe. Which, of course, would also hold back the development of China’s economy, and by extension its military, education and R&D, and international alliances.

What all this makes clear is that behind the current climate change agenda is a geopolitical ploy by the United States. At the heart of the agenda being pushed by the United States is not a sincere concern for the environment, but rather an ambition to remain the world’s leading superpower. This is further evidenced by the fact that the United States’ Special Envoy for Climate is part of the State Department, which is responsible for foreign affairs and securing the interests of the United States internationally. The role is not part of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the agency of the United States government tasked with environmental protection matters. The Special Envoy for Climate is also a member of the United States’ National Security Council, which is the country’s main body for managing national security and foreign policy issues. The role of the United States’ Special Envoy for Climate is therefore to manage the global collaboration to address climate change in such a way that it supports the United States’ hegemony in the world, by creating a problem for the United States’ main opponent on the global stage, China, and by creating an international coalition against it.[49]

The role of the United States’ Special Envoy for Climate is therefore to manage the global collaboration to address climate change in such a way that it supports the United States’ hegemony in the world

Therefore, what the countries of the developing world were warned about in the run up to the Stockholm Conference of 1972, that the global collaboration to address pollution and environmental damage would be used by the countries of the developed world to hold them back in their development, has indeed come true. The United States has manipulated the process such that it became a geopolitical ploy to “kick away the ladder” to development for countries that refuse to accept the United States as the world’s hegemon.

How Practical is the of the Climate Change agenda?

The reality is that decreasing the emission of greenhouse gases will cost trillions. This is well understood in both the countries of the developed world and those of the developing world. Among the most important discussions during COP in 2021, COP26 in Glasgow, Great Britain, was the financing of this necessary investment, as well as the ending of financing for energy investments that are fossil fuel-based. The prior led to establishment of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), under which banks, insurers and investors with $130 trillion at their disposal pledged to put combating climate change at the centre of their investment decisions.[50] The latter led to an agreement between 20 countries, including the United States, with five development financing institutions, including the European Investment Bank and the East African Development Bank, to end all “…overseas financing for fossil fuel projects…” by the end of 2022.[51]

To finance the efforts to reduce emissions, the countries leading the developed world are promoting the “market based approach” which the United States called for during the Rio Earth Summit. Some of the financing should come in the form of grants by the developed countries to the developing countries, but most of it, they say, should come from banks, companies and philanthropies.[52] This is also what the Business Roundtable, the association which represents the 200 largest companies in the United States in the public debate, has been calling for. “Such a strategy would incentivize the development and deployment of breakthrough technologies needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions”, it says.[53]

This view is flawed for a number of reasons.

The first reason is that this “market based approach” asks the companies that are responsible for the environmental destruction, including climate change, to now solve it. The oil and gas industry, for example, was warned as early as 1959 that the products they manufactured and sold would eventually cause catastrophic climate change. At the “Energy and Man” symposium held at Columbia University in New York, the (then) famous scientist Edward Teller said to the leaders of the oil and gas industry, “…whenever you burn conventional fuel you create carbon dioxide”. This, said Teller, “…causes a greenhouse effect”. So, he warned the oil and gas companies, if the world kept using their products, the ice caps would begin to melt, rising sea levels, and eventually “...all the coastal cities would be covered”.[54]

The role of the United States’ Special Envoy for Climate is therefore to manage the global collaboration to address climate change in such a way that it supports the United States’ hegemony in the world

Apparently, the oil and gas industry paid attention because six years later the president of the American Petroleum Institute (API), the organisation that represents the United States’ oil and gas companies in the public debate, in his annual speech said “…carbon dioxide is being added to the earth’s atmosphere by the burning of coal, oil, and natural gas at such a rate that by the year 2000 the heat balance will be so modified as possibly to cause marked changes in climate”. In response to this awareness the API formed a secret committee called the “CO2 and Climate Task Force” to monitor and discuss the latest developments in climate science. This task force included representatives of many of the major oil companies operating in the United States at that time.[55]

The oil and gas companies also did their own research, which came to the same conclusions. For example, the United States’ leading oil and gas company ExxonMobil knew of climate change as early as 1977, when its senior scientist James Black said to the company’s management committee: “In the first place, there is general scientific agreement that the most likely manner in which mankind is influencing the global climate is through carbon dioxide release from the burning of fossil fuels”. A year later he warned the company that doubling greenhouse gases in the atmosphere would increase average global temperatures by two or three degrees centigrade. In response, the company employed top scientists to launch a research program that empirically sampled carbon dioxide and built climate models. ExxonMobil even spent more than $1 million on a tanker project to investigate how much of this carbon dioxide would be absorbed by the oceans. Yet, instead of responding to this scientifically established risk, the company decided to prevent this knowledge from affecting its business. From the 1980s onward, through organising the International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association (IPIECA)[56] and the Global Climate Coalition[57], the company coordinated an international campaign to dispute climate science and weaken international climate policy.[58]

Another leading oil and gas company, Royal Dutch Shell, recognized in the 1980s that it played a role in global warming and that the threat from rising temperatures was growing. It also performed internal research, which determined that the company generated 4% of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions in 1984 from its production of oil, gas and coal.[59] Shell’s researchers said a one-metre sea-level rise could result. They further warned of “…disappearance of specific ecosystems or habitat destruction…”, predicted an increase in “…destructive floods and inundation of low-lying farmland…”, and said that changes in air temperature would also “…drastically change the way people live and work”. In all, Shell concluded, “…the changes may be the greatest in recorded history”.[60] But, just like ExxonMobil, instead of acting against climate change, Shell too decided to join lobbying and trade groups that promoted climate scepticism and opposed emissions reduction policies by governments.[61]

The French oil and gas company TotalEnergies became aware of climate change caused by greenhouse gases emitted by its operations and products as early as 1971, only to behave in the exact same manner as its competitors. It began promoting doubt regarding the scientific basis for global warming during the 1980s, only to later during the 1990s publicly accept climate science while at the same time campaigning against policies to prevent climate change.[62]

The oil and gas companies not only targeted public officials with their campaigns, but also the general public. Knowing full well the truth of how their operations and products affected the climate, and reality of how this would affect life on earth, they launched advertising campaigns to keep the general public unaware or confused about it all.[63]

This history proves that it makes no sense to now promote a “market based approach” to solving climate change. Effectively this means, namely, placing trust in companies like ExxonMobil, Shell and TotalEnergies, who knowingly and purposely created the climate change problem, and who until today lobby governments against real and impactful solutions to climate change if these threaten their business in any way[64], to now solve it.

The second reason the “market based approach” to solving climate change is flawed, is because it was originally created to prevent it from being solved. The legendary strategic political communication expert E. Bruce Harrison developed this “market based approach”, and promoted it on behalf of the companies he worked for as the solution for the problem of pollution and environmental damage. Harrison’s idea was that by promising to address the pollution and environmental damage they were causing, companies could take on the role of the “reasonable and rational” party, “capable” of solving the resulting problems, and at the same time present the environmentalist movements calling for stricter, government led efforts against pollution and environmental damage as “unreasonable and extreme”.[65] In other words, the “market based approach” was created by companies, not to solve the problem of pollution and environmental damage, but to prevent real and impactful solutions being translated into government policy. Because these real and impactful solutions could have a negative impact on the profitability of these companies.

the “market based approach” was created by companies, not to solve the problem of pollution and environmental damage, but to prevent real and impactful solutions being translated into government policy. Because these real and impactful solutions could have a negative impact on the profitability of these companies

The third reason the “market based approach” to solving climate change is flawed, is that it is being promoted because it enables companies to profit from efforts to undo some of the pollution and environmental damage. The argument for using the “market based approach” to solving climate change is that because companies search for profit, they are better at identifying the most efficient solutions for greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, the solutions that provide more benefit than they cost. Or in other words, the solutions that achieve a good “return on investment”. But, if greenhouse gas emissions and climate change can be solved through investments that deliver a good return, then why haven’t companies made these investments yet? The answer companies give is that the risks associated with making these investments in the countries of the developing world are too high for them. That is why they are calling for international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to provide insurance for these investments. Ff the investment by a company fails to deliver the expected return, for whatever reason, these companies would still get their money back.[66] Effectively this means the proposal for a “market based approach” to solving climate change is to ensures that companies active in climate change adaptation and mitigation will be guaranteed a return on their investment. If their project succeeds, they will be allowed to keep the resulting profits. If it fails, for whatever reason, they will be bailed out by an international financial institution. But, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank are financed by the governments of the countries in the developed world. These governments, in turn, are financed by the people of these countries through the taxes they pay. What the proposal for a “market based approach” to solving climate change is really calling for, therefore, is for the ordinary people of the developed countries to pay taxes, to ensure that the companies which caused pollution and environmental damage to make a profit, are now guaranteed a further profit to undo some of the damage they caused!

At the same time, these international financial institutions are calling upon the countries in the developing world to change their local government regulations in line with the interests of international corporations. This, what is typically referred to as “…strengthening the private sector investment climate…”[67], is in no way different than the Washington Consensus[68] policies that are forced upon countries in the developing world by the IMF and World Bank during times of crisis, and that enable western companies to pillage these countries.[69]

The Climate Change agenda is Intellectually Flawed

The modern capitalist world is founded on the ideas of secularism, utilitarianism, individualism, and freedom. Secularism holds that the human mind is capable of identifying right and wrong, and that the objective of the thinking by the human mind should be identification of the rights and wrongs that lead man to happiness in this world. Utilitarianism holds that the happiness of man is achieved through the presence of pleasure and the absence of pain, and that both pain and pleasure result from material experiences. Individualism holds that every person is unique, and thus that the material experiences that achieve happiness are different for every person. Freedom therefore holds that man should be allowed to follow his own will, and not be coerced by others, such that every person can plot his personal course to happiness, and seek out the material experiences that make him experience it.

These philosophical ideas underlie the capitalist economic system that governs the world. They explain why this economic system is characterised by private ownership and markets, as well as pollution and environmental damage. Private ownership enables man to bring under his control the material things the experience of which he believes will bring him happiness, and to use these things for this purpose. The market is where man can exchange his private ownership, including the labour his body can deliver and the ideas his mind can produce, for the material things he aspires to. Pollution and environmental damage result from this system because it does not properly deal with those things that man can not easily turn into private ownership and exchange on a market, things such as the water in the oceans, the dirt of the land, and the air in the atmosphere. The classical capitalist economists therefore regard these things as the “…free gifts of nature”.[70] Since these things can not become private ownership, and thus can not be freely exchanged on markets, effectively they can not be assigned a price in the capitalist economic system, although their value to everyone are obvious and clear. As a result, in this system man uses and abuses these “free gifts of nature” whenever he deems this to support his quest for private ownership, because it costs him nothing.

That is why in this system, legislation is necessary to prevent environmental damage. In the countries of the developed world, companies used and abused the water, land and air, until the environmental movement raised the alarm and governments implemented regulation. But thereafter these same companies moved their operations to the countries of the developing world, and there they again used and abused the water, land and air, because the governments in the countries of the developing world did not yet have this environmental legislation – or did not enforce it.

The global political conversation to mitigate climate change is not affecting this natural tendency of companies operating in the capitalist economic system. Consequently, regulations to limit a specific pollution or environmental damage tend to lead to a shift in the form of pollution or environmental damage, rather than a real reduction. An example is the energy industry.

The renewable energy segment of the global energy industry, which includes industries such as solar energy, wind energy, and batteries, has increased dramatically over recent years, because renewable energy is considered less pollution than energy from coal, oil or natural gas. But the environmental concern underlying this trend has not caused the energy industry to become more environmentally responsible.

In the case of solar energy, Chinese manufacturers rely on coal for the production of the polysilicon that is at the heart of the solar panel. As a result, manufacturing a solar panel in China emits around twice as much carbon dioxide as manufacturing it in Europe. Nevertheless, China dominates global solar panel manufacturing and most solar panels installed around the world are made in China because the coal-based process is cheaper than the European process.[71] The Chinese solar panels are also designed and manufactured in such a way that they can not be recycled. As a result, just as the blades of the windmills used for wind energy[72], they are simply buried in landfills once their useful life ends. There, they will start to leak the toxic metals they were produced from, such as lead, chromium, and cadmium, into the soil and groundwater, poisoning both.[73]

As to batteries, a significant amount of the lithium used in modern batteries comes from the so-called “Lithium-Triangle” that lies under Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile. To extract it, miners drill holes in the salt flats and pump a salty, lithium-rich brine to the surface, leaving it to evaporate in huge artificial lakes or ponds, after which they can scoop up the lithium. This process uses a lot of water, close to 2 million litres for each ton of lithium produced. This process affects groundwater levels, which directly affects people living in the area, in particular farmers. This lithium mining process also produces toxic substances such as hydrochloric acid. In Tibet a lithium mining company allowed this to leak into a river, thereby polluting it and killing its fish.[74] Modern batteries also require cobalt, which is primarily mined in Congo. The standard mining process dumps mining waste in rivers, polluting drinking water. The dust from the pulverised rock is allowed to pollute the air causing breathing problems.[75] Another key battery component, graphite, is primarily mined in China, through a process which causes air and water pollution, damaging agriculture and human health.[76] The materials in these modern batteries can be recycled, but the cheapest way to do so causes significant further pollution – but nevertheless this process is used on a large scale.[77]

In other words, the switch from coal, oil and natural gas based energy, toward renewable energy, is not truly eliminating pollution and environmental damage. It is rather substituting one form of pollution and environmental damage for another form of pollution and environmental damage because the problem underlying pollution and environmental damage in the capitalist economic system is not addressed. The ideas upon which this economic system is built motivate people in business to focus on the maximisation of profits, and to use and abuse the free gifts of nature if this maximises profits. Therefore, as long as these ideas underlie economic activity, pollution and environmental damage will continue. Legislation to address pollution and environmental damage will, as shown by history, only shift it, either to another region in the world where the legislation is not implemented or enforced, or to another segment of industry as in the case of energy.

[1] “Designing the United Nations Environment Programme: a story of compromise and confrontation”, https://www.umb.edu/editor_uploads/images/centers_institutes/center_governance_sustain/Ivanova-DesigningUNEP-IntlEnvtlAgreementsJournal-2007.pdf

[2] “Rachel Carson and JFK, an Environmental Tag Team”, www.audubon.org/magazine/may-june-2012/rachel-carson-and-jfk-environmental-tag-team

[3] “How ‘Silent Spring’ Ignited the Environmental Movement”, www.nytimes.com/2012/09/23/magazine/how-silent-spring-ignited-the-environmental-movement.html

[4] Nelson was also behind organization of first Earth Day, on April 22, 1970, which since then has become an annual global event. See “Sherman Stock: Legal Counsel for Senator Gaylord Nelson (1963-81)”, https://50.nelson.wisc.edu/our-stories/sherman-stock/

[5] In the 1950s, Strong had turned a small natural gas company, Ajax Petroleum, into one of the largest companies in the industry under the name Norcen Resources. This attracted the attention of one of Canada’s leading investment corporations with interests in the energy and utility businesses, Power Corporation of Canada. In 1961 it appointed Strong as its executive vice president. Strong would later serve the company as its president until 1966. He remained active in the oil and gas industry throughout the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maurice_Strong

[6] Robert Anderson sold the Atlantic Richfield Company, better known as ARCO, to BP in 2000, for a sum of $26.8 billion. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ARCO

[7] “Stockholm: the founding of IIED”, in “Evidence of Hope: the Search for Sustainable Development”, Earthscan Publications

[8] “The Founex Conference”, https://www.mauricestrong.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=146:founex-environment-conference-1971&catid=31&showall=1&limitstart=&Itemid=72, for the text of the Founex report see https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/29847/Earth1.pdf

[9] “Stockholm and the Birth of Environmental Diplomacy”, https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2020-09/still-one-earth-stockholm-diplomacy_0.pdf

[10] https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf

[11] https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200506/cmselect/cmenvaud/1014/6033005.htm

[12] “The Earth Summit: What Went Wrong at Rio?”, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1867&context=law_lawreview; see also “United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3-14 June 1992”, www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992

[13] https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf

[14] “Heating the global warming debate”, www.nytimes.com/1991/02/03/magazine/heating-the-global-warming-debate.html

[15] The United States disagreed with this particular understanding of CBDR and insisted that all countries should be held equally responsible for undoing and preventing further pollution and environmental damage.

[16] “Rendering Rio Moot: Trade Policy at the Earth Summit”, https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/2018-09/Rendering%20Rio%20Moot.%20Trade%20Policy%20at%20the%20Earth%20Summit.pdf

[17] https://legal.un.org/avl/ha/dunche/dunche.html

[18] “What role for China in the International climate Regime”, www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Asia-focus-59.pdf

[19] “The Evolution of the UNFCCC”, www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-environ-102017-030119

[21] https://unfccc.int/process/conferences/the-big-picture/milestones/the-cancun-agreements

[22] “How a ‘typo’ nearly derailed the Paris climate deal”, www.theguardian.com/environment/blog/2015/dec/16/how-a-typo-nearly-derailed-the-paris-climate-deal

[23] https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement

[24] www.unfccc.int/submissions/indc/Submission%20Pages/submissions.aspx

[25] “COP26 climate pledges could help limit global warming to 1.8 °C, but implementing them will be the key”, www.iea.org/commentaries/cop26-climate-pledges-could-help-limit-global-warming-to-1-8-c-but-implementing-them-will-be-the-key

[26] “4 Key Achievements of COP26”, https://unfccc.int/news/4-key-achievements-of-cop26

[27] “Who has contributed most to global CO2 emissions?”, https://ourworldindata.org/contributed-most-global-co2

[28] “Access to Energy is at the Heart of Development”, www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/04/18/access-energy-sustainable-development-goal-7

[29] “Kicking Away The Energy Ladder — How environmentalism destroys hope for the poorest”, www.thegwpf.org/content/uploads/2018/05/Paunio-EnergyLadder.pdf

[30] “The climate debt”, www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2020-04-13/climate-debt

[31] “How do CO2 emissions compare when we adjust for trade?”, https://ourworldindata.org/consumption-based-co2 (utilizing 2015 data); the discrepancy between the countries of the developed world, and the countries of the developing world, has only worsened ever since, see “Humanity’s Uneven CO₂ Footprint”, www.statista.com/chart/26416/average-co%25E2%2582%2582-emissions-per-capita-in-selected-regions/

[32] “Are Countries Providing Enough to the $100 Billion Climate Finance Goal?”, https://www.wri.org/insights/developed-countries-contributions-climate-finance-goal

[33] “The Good, the Bad and the Urgent: MDB Climate Finance in 2020”, https://www.wri.org/insights/mdb-climate-finance-joint-report-2020

[34] “Climate Finance Shadow Report 2020: Assessing progress towards the $100 billion commitment”, https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/handle/10546/621066

[35] “Are Countries Providing Enough to the $100 Billion Climate Finance Goal?”, https://www.wri.org/insights/developed-countries-contributions-climate-finance-goal

[36] “Economics of Adaptation to Climate Change – Synthesis Report”, https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/369529/1/702670ESW0P10800EACCSynthesisReport.pdf

[37] https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/06/1094762

[39] “Financing clean energy transitions in emerging and developing economies”, www.iea.org/reports/financing-clean-energy-transitions-in-emerging-and-developing-economies

[40] “John Kerry says COP26 is ‘bigger, more engaged, more urgent’ than past climate summits”, https://edition.cnn.com/2021/11/02/politics/john-kerry-cop26-amanpour/index.html

[41] “John Kerry Says Major Climate Focus Must Be on Coal Dependent Nations”, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-11-19/kerry-says-major-climate-focus-must-be-on-coal-dependent-nations

[42] “US climate envoy Kerry says China, India, Russia must do more to tackle warming”, www.reuters.com/world/us/us-climate-envoy-kerry-says-china-india-russia-must-do-more-tackle-warming-2021-12-01/

[43] “How the West tried to shift China on climate”, www.politico.eu/article/how-the-west-tried-to-shift-china-on-climate/

[44] “John Kerry calls for investing ‘trillions’ to get big emitters to quit polluting”, www.politico.eu/article/kerry-calls-for-paying-trillions-big-emitters-quit-polluting/

[45] “China coal: why is it so important to the economy?”, www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3121426/china-coal-why-it-so-important-economy

[46] “Can China Have It All in a Coal Transition?: How the CCP Will Struggle to Balance Climate Reform With Labor Concerns”, www.cpreview.org/blog/2021/10/can-china-have-it-all-in-a-coal-transition-how-the-ccp-will-struggle-to-balance-climate-reform-with-labor-concerns

[47] “The Climate Club – How to Fix a Failing Global Effort”, www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-04-10/climate-club

[48] “Green Upheaval – The New Geopolitics of Energy”, www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2021-11-30/geopolitics-energy-green-upheaval

[49] Former U.S. national security advisor H.R. McMaster has called upon the United States to use also the climate change agenda against another adversary, Russia: “Use Climate and Trade Policy to Counter Putin’s Playbook”, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/12/23/russia-energy-us-europe-carbon-tarriff-ukraine-nordstream-oil-gas/

[50] “COP26 coalition worth $130 trillion vows to put climate at heart of finance”, www.reuters.com/business/cop/wrapup-politicians-exit-cop26-130tn-worth-financiers-take-stage-2021-11-03/

[51] “U.S., Canada among 20 countries to commit to stop financing fossil fuels abroad”, www.reuters.com/business/cop/19-countries-plan-cop26-deal-end-financing-fossil-fuels-abroad-sources-2021-11-03/

[52] “John Kerry calls for investing ‘trillions’ to get big emitters to quit polluting”, www.politico.eu/article/kerry-calls-for-paying-trillions-big-emitters-quit-polluting/

[53] “Business Roundtable: Market-Based Solutions Best Approach to Combat Climate Change”, www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-market-based-solutions-best-approach-to-combat-climate-change

[54] “What Big Oil knew about climate change, in its own words”, https://theconversation.com/what-big-oil-knew-about-climate-change-in-its-own-words-170642

[55] Ibid note 53

[56] “Early warnings and emerging accountability: Total’s responses to global warming, 1971–2021”, www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378021001655

[57] “Exxon Knew about Climate Change almost 40 years ago”, www.scientificamerican.com/article/exxon-knew-about-climate-change-almost-40-years-ago/

[58] Ibid note 53

[59] “Shell Grappled with Climate Change 20 Years Ago, Documents Show”, www.scientificamerican.com/article/shell-grappled-with-climate-change-20-years-ago-documents-show/

[60] “Shell and Exxon’s secret 1980s climate change warnings”, www.theguardian.com/environment/climate-consensus-97-per-cent/2018/sep/19/shell-and-exxons-secret-1980s-climate-change-warnings

[61] Ibid note 58

[62] Ibid note 55

[63] “The forgotten oil ads that told us climate change was nothing”, www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/18/the-forgotten-oil-ads-that-told-us-climate-change-was-nothing

[64] “Exxon Lobbyist Caught On Video Talking About Undermining Biden’s Climate Push”, www.npr.org/2021/07/01/1012138741/exxon-lobbyist-caught-on-video-talks-about-undermining-bidens-climate-push

[65] “Spin doctors have shaped the environmentalism debate for decades”, www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/02/21/spin-doctors-have-shaped-environmentalism-debate-decades/

[66] “The Cop26 message? We are trusting big business, not states, to fix the climate crisis”, www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/nov/16/cop-26-big-business-climate-crisis-neoliberal, see also “BlackRock’s Fink Urges World Bank, IMF Overhaul for Green Era”, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-07-11/blackrock-s-fink-urges-world-bank-imf-overhaul-for-green-era

[67] “Climate Investment Opportunities Total $23 Trillion in Emerging Markets by 2030, Says Report”, www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/news_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/news+and+events/news/new+ifc+report+points+to+%2423+trillion+of+climate-smart+investment+opportunities+in+emerging+markets+by+2030

[68] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Washington_Consensus

[69] “Pillaging the World: The History and Politics of the IMF”, Ernst Wolff, Tectum Verlag Marburg, 2014

[70] https://kenan.ethics.duke.edu/the-free-gift-of-nature-a-conversation-with-alyssa-battistoni/

[71] “Behind the Rise of U.S. Solar Power, a Mountain of Chinese Coal”, www.wsj.com/articles/behind-the-rise-of-u-s-solar-power-a-mountain-of-chinese-coal-11627734770

[72] “Wind Turbine Blades Can’t Be Recycled, So They’re Piling Up in Landfills”, www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-02-05/wind-turbine-blades-can-t-be-recycled-so-they-re-piling-up-in-landfills

[73] “The Dark Side of China’s Solar Boom”, www.sixthtone.com/news/1002631/the-dark-side-of-chinas-solar-boom-

[74] “Lichu River Poisoned – Case of Minyak Lhagang Lithium Mine Protest”, https://tibetnature.net/en/lichu-river-poisoned-case-minyak-lhagang-lithium-mine-protest/

[75] “The hidden costs of cobalt mining”, www.washingtonpost.com/news/in-sight/wp/2018/02/28/the-cost-of-cobalt/ , “How the race for cobalt risks turning it from miracle metal to deadly chemical”, www.theguardian.com/global-development/2019/dec/18/how-the-race-for-cobalt-risks-turning-it-from-miracle-metal-to-deadly-chemical

[76] “Green Batteries’ Graphite Adds to China Pollution”, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-03-14/teslas-in-california-help-bring-dirty-rain-to-china

[77] “Experts warn of pollution from unregulated new-energy battery recycling system”, www.globaltimes.cn/page/202104/1221004.shtml