Genghis Khan once said that conquering the world on horseback is easy; it is dismounting and governing that is hard. After almost twenty years the US occupation of Afghanistan came to an ignominious end in 2021. The Taliban surrounded the capital in August 2021 and were poised to take the city. In scenes reminiscent of the helicopters departing from the Saigon embassy roof, US military planes were departing from Kabul airport whilst the Taliban were overrunning Afghan government positions surrounding the runaway.

The West looked with indignation as the Talban stormed into Kabul easily displacing the government that had consumed trillions of dollars. The ease with which the Taliban rested control from the beleaguered Afghan government shocked Western observers and to add insult to injury the jubilation of the Afghan masses to the Taliban take over was palpable even to the most cynical of observers.

Western discourse concerning the Taliban has remained highly politicised. Western allegations that a strict, autocratic system of rule would divest the Afghan people of all hard-won rights proved to be unfounded three years on and the alleged brutal rule of the Taliban of the 1990s was not back. The Taliban have gone to great pains to highlight that it intended to form a meritocratic and inclusive government established upon the principles of the Islam for betterment of all Afghans and the region as a whole.

The Taliban have now been in power for three years, although decades of war and mismanagement cannot be undone in this relatively short period. In this deep dive we look at how the Taliban are progressing from insurgents to rulers.

From Insurgents to Rulers

In their first ever public statement, the Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid took questions and answered in English back in August 2021. This itself was a significant departure from the past and came as a surprise for many around the world as the Taliban had normally been a secretive group with virtually no images of many of its leaders and founders. The politically savvy Zabihullah Mujahid and the equally eloquent Anas Haqqani seemed to indicate a shift to a softer form of governance.

The spokesman summarised the situation in the country at the time: “We have expelled the foreigners and I would like to congratulate the whole nation on this. This is pride, not only for a limited number of people. This is a proud moment for the whole nation. This kind of pride is rare when it can be achieved. The whole nation, after the whole history of the nation and therefore, on the base of this I would like to congratulate the whole nation and I would like to welcome you.”[1]

Three years into the Taliban’s rule there has been a remarkable turnaround in Afghanistan’s governance. For decades Afghanistan was considered one of the ten most corrupt countries in the world. Matters were even worse under US occupation where Afghanistan was ranked 174th on transparency international’s ranking of the most corrupt countries.[2] Despite spending over $146 billion on governance related measures the US had very little to show for its investment. Corruption was not just endemic it was woven into the very fabric of the US occupation. The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), a US government established commission that investigated, reported and prosecuted numerous corruption cases involving Afghan and American contractors was established, but to no avail. Loyalty to the occupation was bought with lucrative contracts and kickbacks making corruption in public affairs the basis of governance in US occupied Afghanistan rather than the exception.

This was especially prevalent at border checkpoints where corruption was a critical part of the political settlement, with power brokers at the centre and in the provinces collecting substantial rents on trade at both official Border Crossing Points (BCPs) and roadside checkpoints in the interior.[3] From a country which had endured four decades of war and been afflicted with the gluttonous corruption of the US installed regime where aid, loans and grants were funnelled into vanity projects, wedding halls and to the Swiss accounts of kith and kin, the Taliban have established a relatively corruption free government.

Grudgingly, western institutions admit that corruption especially in customs and checkpoints has been all but eliminated from a nation where it was considered completely justified for an individual to offer a bribe for the completion of administrative tasks of access to public services.[4] William Byrd of the US institute of Peace notes the Taliban have demonstrated the ability to greatly reduce corruption in customs and at road checkpoints. Taliban efforts have drastically reduced corruption and effectively disassembled a political settlement that rested on a system of patronage where powerbrokers syphoned off as much as $767 million in bribes each year on undeclared goods at official border checkpoints and levied a further $650 million at checkpoints on arterial roads.[5] The Taliban’s efforts have borne fruits, they say revenues from their robust tax collections reached $1.7 billion in the last 10 months.

Grudgingly, western institutions admit that corruption especially in customs and checkpoints has been all but eliminated from a nation where it was considered completely justified for an individual to offer a bribe for the completion of administrative tasks of access to public services

Opium, What Opium

Opium poppy, which grows extensively in Afghanistan’s southern fields, contains the main ingredient used to manufacture heroin. Afghanistan was previously the world’s top opium producer – responsible for over 80% of global supply – and a major source of heroin in Europe and Asia.

Opium production increased astronomically during the US occupation of the country. The US attempted a number of times to deal with this problem and marketed its approach as a major success. The invasion of the poppy fields was called Operation River Dance, and was touted by the US as a major escalation in its war on opium. It was a two-month eradication campaign in 2008 where the Afghan government was lauded with praise and the US took credit. But we now know as was revealed in the Afghanistan papers none of this was true and US officials, soldiers and Afghan officials all knew this too. The strategy entailed paying farmers to destroy their poppy crop, but they continued to grow them as others were paying them even more to grow their crops, this included Afghan government officials.

In November 2023 the Taliban achieved another milestone that two decades of western occupation failed miserably in. A UN report published in November 2023 confirmed poppy cultivation and opium production plunged more than 90% in Afghanistan since Taliban authorities banned the crop in April 2022. Poppy cultivation dropped by around 95 percent – from 233,000 hectares at the end of 2022 to 10,800 in 2023.[6]

The Taliban achieved in two years what the US failed for 20 years.

Circumventing US Sanctions

The Taliban did not in fact inherit an economy from the US occupation rather it inherited a kleptocracy which, by design rather than by default, fostered corrupt and inefficient governance wholly reliant on the handouts provided by the US.[7] Little or no development took place under 20 years of US occupation, with manufacturing at an all time low and opium cultivation at an all-time high.[8] Although the West blame the Taliban for the current economic situation of Afghanistan, prior to the Taliban’s August 2021 takeover, a severe humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan, due primarily to almost four decades of conflict already existed. [9] The situation was severely exacerbated by the abrupt withdrawal of aid and the seizure of $9 billion of central bank assets located in New York.

The World Food Programme reported in September 2021 that the proportion of Afghans reporting insufficient food consumption was 80% even before the Taliban takeover.[10] The UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimated that “…at least 1 million…” Afghan children were “…at risk of dying due to severe acute malnutrition without immediate treatment.”

Afghanistan faces an acute economic crisis, not due to the Taliban but due to the abrupt loss of more than $8 billion a year of civilian and security aid from the US and other foreign donors and a run on Afghan banks due to banking sanctions imposed by the US. To make matters worse the forced expulsion of over 1.7 million Afghan refugees from Pakistan further strained Afghanistan’s economy and resources.

Although some may argue that the world does not owe Afghanistan a living, Afghanistan’s stunted development is a direct consequence of western interference, invasion and occupation. The US seizure of Afghanistan’s Central Bank reserves and subsequent sanctions meant the Taliban government could not even move money around via the SWIFT system. Although the Taliban achieved stability and were successful in providing broad territorial access to humanitarian agencies, their inability to move funds and withdraw cash from the banking system hampered efforts to alleviate the suffering of the Afghan people. In desperation, UN agencies established a program of physical cash shipments, whereby US dollar notes are flown into Kabul for use in meeting salaries and other domestic payment needs. Such shipments have now reached substantial volumes, with up to $150 million being flown into Afghanistan every month. This underlines the stability and security that the Taliban achieved in Afghanistan under the previous regime; the general state of lawlessness would have prohibited such an endeavour. [11] In Afghanistan, cash has most definitely become king. Afghanistan still depends on development aid today.

Afghanistan faces an acute economic crisis, not due to the Taliban but due to the abrupt loss of more than $8 billion a year of civilian and security aid from the US and other foreign donors

Kandahar, the second largest city in Afghanistan is now supplied with electricity from the Kajki Dam in Helmand. The second phase of Kajki Dam was inaugurated in April 2024.[12] The repair and construction of a 900 km long highway connecting the major cities of Afghanistan, which was damaged due to the transfer of heavy military equipment for two decades, has been started with the cooperation of the private sector. The Taliban government also started the Qashtipa Canal, which takes water from the Amu River to irrigate the desert areas of the country that span three provinces. This six-year project is being run by Afghan engineers and Afghanistan’s funds with no external support.[13]

Afghanistan’s Ministry of Mines and Petroleum announced recently that it collected 13.2 billion Afghanis in revenue in the past year. Speaking at a press conference as part of the new ministerial accountability program, Shahabuddin Delawar, acting minister of mines and petroleum, said that the ministry signed contracts for the extraction of 158 small mines over the past year. “There has been full transparency in mining contracts and the tender process [is done] openly,” Delawar said. He said that work is underway on eleven major mining projects including some which were contracted by the previous government. “These projects can take the country out of the economic crisis and some local and foreign investors are very interested in investing in them.” He confirmed the ministry is committed to counter corruption and will never allow corruption to permeate the mining sector.

More recently the Taliban retendered and awarded China’s Xinjiang Central Asia Petroleum and Gas Co, or CAPEIC the major Amu Darya oilfields project where the company will invest $49 million in Afghanistan’s oil production which has already helped boost the country’s daily crude oil output to more than 1,100 metric tons.[14]

Whilst the Taliban government is being restricted in accessing the global economy and financial system it’s clearly made some important headway in some areas to maintain economic development and growth. Whilst claims of imminent economic collapse continue in the Western media the Taliban in its first three years have shown that with determination and a belief in one’s people and system of governance work-arounds can be achieved. Since November 2021 wages for civil servants and other state employees have also been paid on time and any outstanding payments have been fulfilled. Pensions for retired workers have also been paid and any outstanding balances have been settled.

Whilst claims of imminent economic collapse continue in the Western media the Taliban in its first three years have shown that with determination and a belief in one’s people and system of governance work-arounds can be achieved

There are no “silver bullets” that will revive Afghanistan’s economy. But what can be garnered from the past 3 years is that good principled governance leads to the reduction of corruption and nepotism and this will help economic development.

Bringing Peace to the Jungle

A startling statistic exemplifies the change in Afghanistan security situation, since the withdrawal of US Troops. Annual deaths rates due to terrorism have dropped 1250%. In 2024 there were 119 fatalities and 229 injuries whilst under US occupation in 2020 there were 8820 civilian casualties of which 3035 were fatalities.[15]

Despite Western claims of fighting terrorism and creating a safe and stable Afghanistan it was under US tenure in 2015 that IS-KP gained its foothold in Afghanistan.[16] What ensued was a Taliban-IS-KP conflict that claimed the lives of hundreds of Taliban soldiers. The Taliban have long held suspicions that IS-KP’s entry into Afghanistan was at least facilitated if not planned by the US as a means of bringing the Taliban to the negotiating table. The IS-KP presence in actuality did factor strongly in the Taliban’s decision to parley with the US and ease the US departure from Afghanistan.

The American presence in Afghanistan was supposed to foster meritocratic and just governance. Instead, like all its occupations and wars preceding Afghanistan, the US built a corrupt, dysfunctional and barbarous Afghan government which relied completely on US patronage to exist. Individuals like General Dostum the Uzbek warlord famous for suffocating hundreds in shipping containers, and the Tajik warlord Abdullah Abdullah featured heavily in the US constructed regime.[17]

The security infrastructure established by the US in Afghanistan like that of any colonial endeavour was focused on maintaining its presence and not to provide safety and security for the Afghan population. Night-time raids, torture, imprisonment, the prosecution of personal vendettas using the organs of state and a general state of lawlessness were hallmarks of the US presence.[18]

The Taliban on the other hand does not constitute a colonial force. Rather, in a succinct departure from its previous incarnation, the Taliban effectively neutralised armed opposition by engaging with minority groups like the Shi’ah Hazara minority and offered a general amnesty to all opposition figures and fighters. This surprised many western commentators, whilst many former government officials fled other former regime officials like Hamid Karzai, the former president of Afghanistan and Abdullah Abdullah former defence minister chose to stay, and remain to this day unharmed by the Taliban.[19] In an interview Mawlawi Burjan said that Afghan history was a continuous cycle of violence and that it had to stop. “The Taliban have learned that they mustn’t behave as they did in their previous government. That only pushes people to resist and fuels the opposition. The Afghan tradition of vendettas and bloods feuds have been set aside for stability and security.”[20]

The Taliban effectively neutralised armed opposition by engaging with minority groups like the Shi’ah Hazara minority and offered a general amnesty to all opposition figures and fighters

Despite significant bellicosity, former regime elements have largely been neutralised by the Taliban either by force, coercion or amnesty. Two decades of resistance created a disciplined force which the Taliban have used effectively to establish law and order in Afghanistan. Kidnapping, formerly endemic, are rare and highway robbery, also formerly prevalent, is also much reduced. [21]

The main security challenge to the Taliban remains IS-KP who have carried out several small but significant operations in 2024. They do not pose an existential or a significant challenge to the Taliban and are confined to a few strongholds and appear to mainly target the Shi’ah Hazara community.

Three years on, Afghanistan is safer and less violent than it has been in decades. The International Crisis group’s senior Afghan consultant on a trip to Kabul in June 2022 highlighted the situation: “The first thing is the remarkable degree of calm that has settled over Kabul, despite recent attacks. The relative quiet is something you feel almost every moment of the day. I slept with the windows open and the only sounds I heard at night were the calls to prayer, a contrast with previous years when I grew accustomed to gunfire or the roar of low-flying helicopters in the darkness. Body searches at the entrances to many buildings have been downgraded from intense screenings to quick pat-downs or a desultory shrug……….. nothing like the carnage of previous years.”[22]

Three years on, Afghanistan is safer and less violent than it has been in decades

Today, Kabul resembles the rest of Afghanistan, it is conservative and peaceful and quiet, and the Afghan people are relieved the war is over. The amnesty the Taliban gave to all officials of the previous regime was a major departure from Afghan history and almost unique in Afghan culture. Getting revenge and settling scores has been the norm in the many bloody regime changes that have taken place in Afghan history. Despite Western claims the Taliban would undertake reprisals, they did not transpire. The breaches of amnesty that have occurred have been with former special forces, those that were the hammer of the previous regime who committed atrocities against the Taliban and their supporters

Funding Girls Education

Nothing has gained more Western attention than women and the education of girls in Afghanistan. For the Taliban, western interference in the Muslim lands concerning the rights of women is seen from the lens of the imposition of western liberal norms on the Islamic world and attempts at population control. They point out that during the US occupation of Afghanistan the rate of admission for girls in primary school was 36% whilst under the Taliban it is 60% a significant improvement in relatively short time.[23] Such a low rate of female inclusion during the two decade occupation did not elicit howls of outrage from western critics.

Furthermore, the Taliban claim that western criticism is based on the observed reality of the levels of female participation in the workplace in several neighbouring countries. For the Taliban who rule over a nation critically short of finances, educating women to university level is simply not an appropriate use of scant resources for the short to medium term.

When the Taliban took power in August 2021, they reiterated their commitment to protecting women’s rights within the framework of the Shari’ah. “The issue of women is very important. The Islamic Emirate is committed to the rights of women within the framework of Sharia. Our sisters, our men have the same rights; they will be able to benefit from their rights. They can have activities in different sectors and different areas on the basis of our rules and regulations: educational, health and other areas. They are going to be working with us, shoulder to shoulder with us. The international community, if they have concerns, would like to assure them that there’s not going to be any discrimination against women, but of course within the frameworks that we have. Our women are Muslim. They will also be happy to be living within our framework of Sharia,” said Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid in the Taliban’s government’s first press conference.[24]

For the Taliban government education remains a medium to long term priority. After nearly five decades of continuous war, security and the economy are the priorities, especially due to the scant resources the nation has

In the immediate aftermath of the takeover, Taliban leaders called on female government employees to return to their posts, as long as they were wearing the hijab (headscarf), and granted “amnesty” to all men and women who worked with foreign powers. Shortly after the Taliban called for women to stay home temporarily, citing concerns over new Taliban forces who “…have not yet been trained very well…” and “…who may mistreat, harm, or harass women.”[25] But in May 2022 the Taliban reversed the decision to re-open girls’ high schools and this for many confirmed the Taliban was never serious about women’s rights. But on closer examination of this issue it reveals a more complex picture.

The announcement the day before high schools were to re-open came from Taliban supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada, rather than the government in Kabul. The Kabul government itself was surprised as all officials were constantly saying high schools would reopen and were making arrangements for them to restart. Whilst girls’ education gets much western media coverage the Taliban is a vast movement consisting of multiple different shura’s with multiple, often competing views. This struggle, much like the Taliban’s past, continues today within the movement, with rank and file of the movement grumbling over many issues.

Whilst girls’ education gets much western media coverage the Taliban is a vast movement consisting of multiple different shura’s with multiple, often competing views

The view from the Taliban is far from monolithic. Abdul Salam Zaeef, a former senior Taliban official, has criticised the restrictions on female education saying: “Those who oppose modern education or invent arguments to undermine its importance, they are either completely ignorant or oppose Muslims under the garb of Islam,” he wrote on X, formerly Twitter, on the 5th of March, 2024. The Taliban’s deputy foreign minister, Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, called on the government to rescind the ban on women’s education. “Learning should be open to all because education is obligatory for both men and women,” he said. “No country can progress without education.”[26] Dissenting voices point out that the ban of female secondary education has no precedent in Islamic theology but rather is the result of Afghan cultural norms.

Many Afghans see the schooling system of education as westernisation and prefer the traditional madrassa system. The madrassa system has for long dominated Afghanistan. The western schooling system is less than 100 years old in the country. This is why the modern schooling system is viewed as a westernisation effort that impeaches the nation’s culture. Intra-movement concerns drove the policy reversal rather than foreign relations. Maintaining the cohesiveness of the movement mattered more to the Taliban, the need to maintain unity was more important, even if it meant millions of girls don’t go to school.

Therefore the policy U-turn on girls’ education was an internal matter in the direction of the Taliban movement. Reflecting on this, the New Yorker said: “The question of women’s rights is perhaps the greatest unresolved issue in the new Afghanistan. After taking power, the Taliban leadership announced that girls up to the sixth grade could resume schooling, but for the most part older girls had to wait until “conditions” were right. When I talked with Mujahid, the spokesman, he was vague about what those conditions were, and about whether women would be allowed to work. The impediment was funding,” he said. “For education and work, women need to have separate spaces,” he explained primly. “They would also require special separate means of transportation.” But, he added, “…the banks are closed, the money is frozen.”[27] The need to provide transport, Islamic uniforms etc when the government has little money was the primary justification for the U-turn on girls’ high school education.

For the Taliban government education remains a medium to long term priority. After nearly five decades of continuous war, security and the economy are the priorities, especially due to the scant resources the nation has.

Foreign relations

The Taliban announced in its first press conference after taking over that “…we do not want to have any problem with the international community” and that it wanted to have relations with all its neighbours.[28] The Taliban have adopted a very pragmatic approach to foreign relations especially with its immediate neighbours. Economic and security interests have trumped ideology when dealing with bordering states especially when dealing with China.

The prospect of renewed Taliban rule sparked some anxiety among the region’s powers but also a degree of relief, as the US was not a welcome presence for the Russians and Chinese. However, the vacuum left by the implosion of the US sponsored regime on its departure was also a source of deep concern for the region. Hence the prospect of a stable government even with the Taliban at its helm was grudgingly welcomed by all.

The Taliban have sought to capitalise on its neighbour’s desire to see a stable Afghanistan. It has engaged in diplomacy with countries in the region, China, Pakistan, Iran, Russia, and Central Asian countries. The Taliban encouraged countries to keep their embassies open and foreign businesses and aid organisations to continue work in Afghanistan.

US: Despite over a decade of informal and formal talks US-Taliban relations remains tense as the US extrication from Afghanistan was a painful moment in US history that was marked by the abandoning of equipment and allies in its haste to leave.

More than security, ideological concerns guide US policy towards the Taliban. A successful display of political Islam destabilised US sponsored regimes from Pakistan to the Middle East. Hence US policy has evolved to contain the nascent Taliban state without precipitating its implosion. Competing objectives betray a schizophrenic attitude where outright theft of Afghanistan Central Bank assets are combined with meetings between the CIA and the Taliban to discuss cooperation against IS-KP.[29] Instrumental to US efforts has been the pressure exerted on Pakistan to fortify its border with Afghanistan and enactment of punitive measures against the Taliban and Afghanistan’s economy.[30]

Russia – Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov welcomed the possibility that the Taliban might form a new government, and while the US and most other countries evacuated their embassies, Russia’s remained open and under the group’s protection, with the Russian authorities later granting Taliban the Afghan Embassy in Moscow.[31] Although Russia has seen the Taliban as a terrorist organisation in the past, in recent years Russia has engaged with the Taliban. Moscow came to see engagement with the Taliban as a strategic necessity. Moscow forged ties with the group’s political representatives in July 2021. As the Taliban were rapidly gaining ground, the Kremlin hosted representatives in Moscow, where the Russian special envoy for Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, sought assurances that the group would not try to expand into the Central Asian states and would refrain from targeting Russian diplomatic missions.

Russian and the Taliban follow a pragmatic and transactional relationship where, due to its engagement in Ukraine, Russia prioritises security and stability in its relations with the Taliban.

China – Sino-Taliban relations have been evolving for decades and are predicated on economics and security. Whilst China has maintained a low profile in Afghanistan, meetings between the two have increased in recent years. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s has made a number of trips to Kabul since the Taliban takeover in August 2021.[32] Beijing’s traditional worry in Afghanistan has been regional instability and the prospect of cross-border aid to Uyghur militants in Xinjiang—or the provision of a safe refuge for Uyghurs fleeing Chinese oppression.

But the Taliban appear to be prioritising their economic relation with China over any ideological concerns. The Taliban have allayed China’s paranoia of the past two decades concerning the harbouring of enemies in the surrounding nations. The Taliban’s reported ‘removal’ of Uyghur militants from the Afghanistan-China border area reflects a desire and presage for closer ties, including security cooperation, between the two countries.[33] China has agreed to a number of mining projects but the lack of security stalled such ambitious projects. China has already built extensive transportation infrastructure through the Central Asian countries north of Afghanistan. For their part, the Taliban have indicated they intend to cooperate closely with China, with a Taliban spokesperson reportedly suggesting in one foreign media interview that China would be the Afghan government’s most important partner going forward.[34]

Pakistan – The military of Pakistan and the Inter-Services Intelligence – the ISI, have relations that go back decades with the Taliban. Contrary to what is suggested in western media the Taliban is not monolithic, relations between the Pakistan military and the Taliban wax and wane. Through coercion and guile Pakistan played a central role in pressuring the Taliban to sit down with the US for peace talks which were designed to give a face saving exit for a weary US from Afghanistan. [35]

Afghanistan and Pakistan have long had an ethnically tinged dispute over their shared 1,600-mile-long border – the Durand Line. Taliban leaders are having to deal with the same challenges as previous governments against Pakistani efforts to build fences along the Durand Line, which Islamabad sees as the formal Afghan-Pakistan border. Forty-seven people were killed in air raids in Khost and Kunar reportedly carried out by the Pakistan military in 2022.[36] These attacks sparked protests and once again fuelled border tensions. There remains an uneasy alliance between the two, with a deficit of trust on both sides.

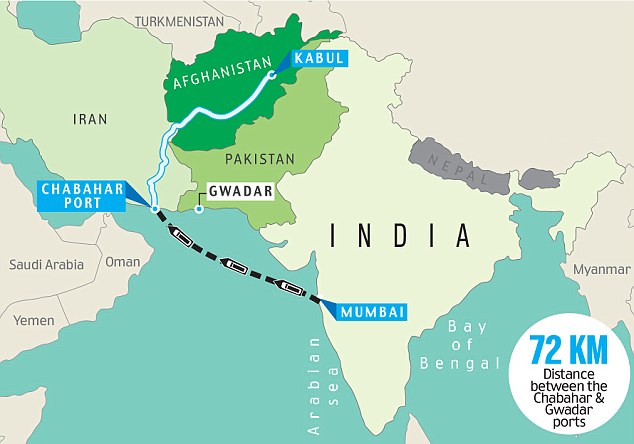

From the Taliban’s perspective, Pakistan is crucial to US efforts to economically and diplomatically strangle and contain the Taliban, whilst the Pakistanis fear that the Taliban have ambitions to include both the NWFP and Balochistan into an expanded Afghanistan. More importantly Pakistan sees the Chabahar port project as an attempt by Afghanistan to mitigate the importance of Pakistan to Afghanistan and see this project as a direct competition to its own Gwadar port which is only 72 km to the east.[37]

Any feeling of good will between Pakistan’s Generals and the Taliban have been squandered by Pakistan’s subservience to US policy on Afghanistan.[38] Instead of attempting to build strong relations to mitigate the influence of India and other powers in Afghanistan, under US Influence Pakistan’s adversarial approach to the Taliban and its attempt to stifle development and the regional integration of Afghanistan has pushed Taliban closer to other regional powers especially India.

The Taliban now firmly in charge are no longer reliant on Pakistan’s duplicitous assistance and it seeks to build a foreign policy independent of Pakistan.

India – At first the biggest loser of the fall of the US backed regime in 2021 was India. India had invested in the American backed government in Kabul and maintained an intimate relationship with the Northern Alliance based regime. India had no diplomatic relations with the Taliban at the time and Indian officials eventually visited Afghanistan for the first time since the Taliban took control on the 6th of June 2022. A delegation led by J.P. Singh, a secretary overseeing India’s external affairs with Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran, travelled to Kabul to discuss the delivery of humanitarian aid with Taliban leaders.

The diplomatic visit reflects India’s new policy of engagement with the Taliban government in Afghanistan,[39] given the new geopolitical realities of the region now that the Pakistan-backed Taliban (in India’s eyes) appears poised to retain control of the strategically important landlocked nation for the foreseeable future. For India, having a foothold in Afghanistan is necessary to counter Pakistan’s presence and influence in Afghanistan. The close Pakistan-Taliban relationship poses a threat to Indian interests in the region because it increases Pakistan’s strategic depth and security against India.

On its part the Taliban see India as a more reliable partner than the duplicitous Pakistan whose foreign policy is completely dependent on US dictates. Mullah Yaqub, the Afghan government’s acting defence minister and son of the Taliban’s founder, has hinted at Kabul’s willingness to work with India and even send Afghan defence troops to India for training.[40]

Iran – Although the Iranian government welcomed the departure of US troops from Afghanistan it viewed the return of the Taliban with a degree of apprehension. Staunchly Sunni, the Taliban have in their past incarnation been known for their dislike of all things shi’ah. President Ebrahim Raisi celebrated the US withdrawal as a “defeat” and called for national unity in the country. Iran’s interests in Afghanistan include preserving its historic influence in western Afghanistan, protecting the Afghan Shi’ah minority (the Hazaras), and reducing the flow of refugees into Iran (Iran hosts millions of documented and undocumented Afghans). From enthusiastically cheering the departure of the Taliban to grudgingly accepting their return, Iran’s policy has pivoted to accommodate the geopolitical reality they find themselves facing. Iran has adopted a reluctant engagement despite clerical reservations, with Grand Ayatollah Lotfollah Safi Golpaygani, one of Iran’s most senior clerics warning that engaging with the Taliban is a “...grave and irreparable mistake…” and urged the government and the international community to act with “...seriousness…” to avert further “…Taliban aggression against oppressed Afghans”.

Despite the traditional hostility between Tehran and the Taliban, Iran has sought a more positive arrangement with the new Taliban administration. Its primary concern is the inclusion of Shi’ah elements in the new Kabul administration, which disappointingly for Tehran failed to materialise.[41]

Iran has now formalised relations with the Taliban handing over the Afghan embassy to the Taliban officially on the 26th of February 2024 and unlike Pakistan has proactively sought to improve relations with the Taliban.[42] From developing local airports to helping with higher education, Iran has engaged with the Taliban to improve bilateral trade and cooperation.

Conclusions

The leadership of the Taliban has been at pains to spread a very different message to avoid the same tragedy that took place in the 1990s. They have scrambled to order their ground forces to operate with restraint and to persuade all Afghans of their good intentions. The Taliban leaders immediately declared a general amnesty for anyone who worked for the previous regime and also asked government officials and journalists, including women, to return to work and even reached out to minority groups to assuage their concerns.

But the West are not convinced and their media and officials have gone into overdrive to paint the Taliban in negative terms. Promises the Taliban have made concerning the rights of Afghan citizens, ethno-religious minorities, women, and the educated middle classes in general have been ambiguous and often contradictory. There are clear divides within the Taliban movement between those who are opposed to making any concessions and those that want to gain international legitimacy. The Taliban after three years of rule face immense security, economic and social challenges. These all take place while the US and its allies continue pressurising the Taliban on these issues in the hope the Taliban make compromises and concessions to Western demands.

The Taliban have still not outlined how its Islamic system will work or detailed its shape and structure. When the Afghan information ministry was asked about their government structure looking very similar to the previous regime and western democracies they answered it was not un-Islamic to have an acting Prime minister and deputy Prime ministers, as they are all answerable to the Amirul Momineen, who the Taliban see as the head of the system.

After three years of Taliban rule the Taliban’s primary focus has been on issues within Afghanistan and within the movement. They have made progress on economic development and in relations with surrounding nations. But after decades of war numerous challenges remain which the Taliban will have to solve if they want to remain in power for the long term.

[1] Transcript of Taliban’s first news conference in Kabul | Taliban News | Al Jazeera

[2] Can the Taliban Tackle Corruption in Afghanistan? (voanews.com)

[4] Taliban: MP claims Afghanistan a ‘country transformed’ – BBC News

[5] Ibid

[6] Afghanistan opium cultivation in 2023 declined 95 per cent following drug ban: new UNODC survey

[7] America enabled Afghanistan’s corruption for years. The Taliban knew it. (nbcnews.com)

[8] Afghan opium poppy cultivation plunges by 95 percent under Taliban: UN | Taliban News | Al Jazeera

[9] The Economic Disaster Behind Afghanistan’s Mounting Human Crisis | Crisis Group

[10] Afghanistan Food Security Update, World Food Programme, September 10, 2021.

[11] Towards Economic Stabilisation and Recovery, Afghanistan Development update, April 2022, World Bank, pg 8, ADU-2022-FINAL-CLEARED.pdf (worldbank.org)

[12] Deputy Prime Minister of Taliban: “Kajki” dam is full of water | webangah news hub

[13] The Qosh Tepa Canal: A Source of Hope in Afghanistan – The Diplomat

[14] Afghan Oil Production Jumps With $49 Million Chinese Investment (voanews.com)

[15] People killed by terrorism in Afghanistan 2022 | Statista

[16] See, Islamic State–Taliban conflict – Wikipedia

[17] The Warlord Who Defines Afghanistan: An Excerpt From Bruce Riedel’s ‘What We Won’ | Brookings

[18] “They’ve Shot Many Like This” Abusive Night Raids by CIA-Backed Afghan Strike, Human Rights Watch, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/afghanistan1019_web.pdf

[19] Hamid Karzai stays on in Afghanistan — hoping for the best, but unable to leave : NPR

[20] Zain Samir · Is this a new Taliban? Afghanistan after the Exit (lrb.co.uk)

[21] Taliban publicly display bodies of alleged kidnappers in Herat | Afghanistan | The Guardian

[22] Smith, G, A Short Visit to the Taliban’s Tense and Quiet Capital, International Crisis Group, 9 June 2022, A Short Visit to the Taliban’s Tense and Quiet Capital | Crisis Group

[23] Afghanistan Welfare Monitoring Survey, World Bank, October 2023 Afghanistan-Welfare-Monitoring-Survey-3.pdf (worldbank.org)

[24] Transcript of Taliban’s first news conference in Kabul | Taliban News | Al Jazeera

[26] The Azadi Briefing: Taliban Appears Split Over Women’s Education Ban (rferl.org)

[27] The Taliban Confront the Realities of Power, The New Yorker, 28 February 2022, The Taliban Confront the Realities of Power | The New Yorker

[28] Transcript of Taliban’s first news conference in Kabul | Taliban News | Al Jazeera

[29] Taliban, CIA To Boost Anti-IS-KP Efforts in Upcoming Doha Meeting – The Media Line

[31] Russia Hands Over Afghan Embassy in Moscow to Taliban (voanews.com)

[32] China Signals It’s Back to Business as Usual With Taliban Government – The Diplomat

[33] Taliban ‘Removing’ Uyghur Militants From Afghanistan’s Border With China, rferl.org, 5 October 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/afghanistan-taliban-uyghurs-china/31494226.htm

[34] Mattia Sorbi, “Afghanistan, il portavoce dei talebani Zabiullah Mujahid: ‘Chiediamo all’Italia di riconosceri. La Cina ci finanzierà,” La Repubblica, September 1, 2021.

[36] ‘Life destroyed’: Afghan civilians describe alleged border raids, Al Jazeera, 5 October 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/4/21/life-destroyed-afghan-civilians-describe-alleged-border-raid

[39] India engaging the Taliban in ‘various formats’, says MEA spokesperson – The Hindu

[40] Taliban see ‘no issues’ in sending army personnel to India (tribune.com.pk)

[41] Iran insists on ‘inclusive’ government in Afghanistan | Taliban News | Al Jazeera

[42] Iran Formalizes Ties with the Taliban | The Washington Institute