The 10th China-Arab States Cooperation Forum concluded on 30th May 2024 with a joint statement on the on-going war in Gaza. Addressing Arab leaders, Chinese premier Xi Jinping said Israel’s war on Gaza “…should not continue indefinitely…” and “…justice should not be absent forever”. In his keynote address, the Chinese leader also said China was willing to work with Arab countries to deepen cooperation in fields ranging from oil and gas to trade and investment, as well as forge new areas of growth such as in artificial intelligence. “China will further strengthen strategic cooperation with the Arab side in oil and gas and integrate supply security with market security,” he said. Chinese ties with the Middle East rulers have grown over the past decade and this has worried several US policy makers. Despite the media coverage and calls for concern, China remains a lightweight in the strategic region and this is unlikely to change in the near term.

Up until the 1990s China was virtually absent in the Middle East. Aside from supplying cheap, hard-to-get weaponry for states such as Iraq, Iran and Saudi Arabia, China had no economic and diplomatic ties. China looked at the Middle East as an arena where the US and Soviet Union were competing with each other, and China’s foreign policy was focussed on its desire to isolate Taiwan and trying to get much of the world to recognise Beijing as the legitimate ruler over all of China. In the months following the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre, the Middle East leapt to prominence for China as Western capitals ostracised Beijing and imposed sanctions. By 2000, all states in the Middle East had broken official ties with Taiwan and established full diplomatic relations with the Communist Party, which they recognised as the sole legitimate government of all of China.

The Thirst for Oil

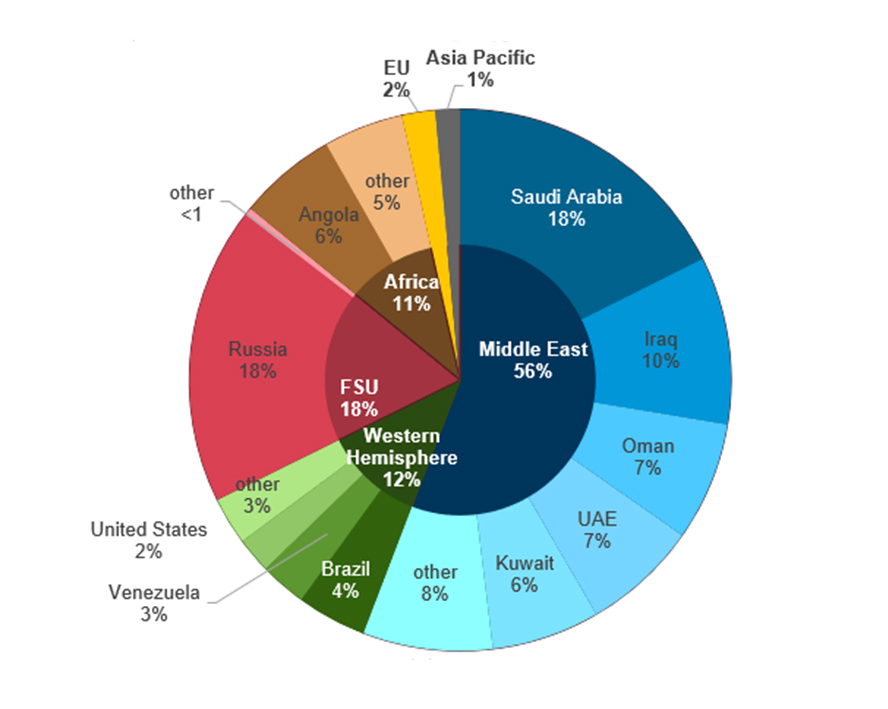

In 1993 China was unable to fulfil its domestic energy needs from domestic production and it turned to the Middle East for its energy imports. By 1995 the Middle East became the number one source of oil for China. China’s rapid growth and stature as well as enormous population means it needs supply lines for raw materials, commodities and more importantly oil, and this is where the Middle East came into the picture. China consumed 15 million barrels per day (mbd) of oil in 2022. But only 5 mbd of this is from domestic sources, leading China to surpass the US as the top global importer of oil in 2017. There are 45 nations that fulfil China’s demand for oil; over half of this oil comes from nine countries in the Middle East, with Saudi Arabia providing the lion’s share. China’s most important reason for being present in the Middle East is energy. The Middle East will remain China’s largest source of oil imports and that is the strategic significance of the Middle East.

The Middle East has also grown in importance for China as the US and Europe engage in a trade war with Beijing. With western markets likely to place further restrictions on Chinese goods, the Middle East with its growing population will become even more important for Beijing.

Trade data over the past six years underlines the shift. China and the Middle East traded $507.2 billion of goods in 2022, according to customs data, double the level in 2017. Trade with the Middle East rose 27% in 2022, surpassing the growth with Southeast Asian nations (15%), the European Union (5.6%) and the US (3.7%). Over 80% of Chinese trade with the region is over petrochemicals. China also now has at least 20 port projects along critical maritime passages that straddle the Middle East and North Africa. China enjoys comprehensive strategic partnerships or strategic partnerships with 12 Arab countries, and 21 Arab states, along with the Arab League, all have formally signed onto the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The Iran factor

The Iran–China 25-year Cooperation Program agreement was announced in July 2020 and led to much speculation regarding its impact in the volatile Middle East region. The possibility of China securing vital commodities, providing a lifeline to the embattled regime in Tehran, establishing a strategic footprint in the region and challenging the US were seen as real possibilities with the deal.

Beijing committed to investing in Iranian oil and gas sectors, constructing railroads and improving manufacturing. In exchange, Iran agreed to provide energy to China at a special discount. The deal also incorporated strong military cooperation between the two nations.

But nearly 5 years on little progress has been made, whilst Iran’s isolation has got worse. Iran in the past turned to China to relieve economic pressure but China doesn’t have a good track record of delivering. Not surprisingly there are a lot of promises in the China-Iran Cooperation Programme, but many challenges will need to be overcome for this strategic deal to come to fruition. Whilst it’s too early to assess its impact, for the moment it’s a deal that remains on paper.

Iran in the past turned to China to relieve economic pressure but China doesn’t have a good track record of delivering

The gathering of the Middle East leaders in Beijing saw a lot of fighting talk about the Gaza war and the broader issue of Palestine. China has criticised the western position of supporting Israel in its genocidal war. Despite China’s two-decade involvement in the region it hasn’t got involved in arbitrating local disputes. China has called for a Palestinian state, but this has been the long-term plan of the US. Even Chinese mediation between Iran and Saudi Arabia in 2023 was in coordination with the US and Saudi officials remained in close contact with US officials as the talks progressed.

China’s challenge in the Middle East is the fact it has no security presence that would allow it to impose and maintain its diplomatic architecture in the region. The US maintains influence in the Middle East through vassal states, through its maintenance of Israel and its military presence via bases, troops and aircraft carriers in the region. China’s military involvement in the region remains virtually non-existent so far. China’s naval base in Djibouti is the most visible sign of Beijing’s regional presence. But for the moment China looks happy with pursuing trade under the US regional security umbrella.

Beijing has traditionally preferred the promotion of trade and investment in the region and whilst its ambitions in the Arab world have expanded beyond trade in recent years, trade is dominated by petrochemicals. Beyond oil, Chinese officials seem to be more interested in courting Muslim-majority nations in the Middle East to temper international criticism of the Communist Party’s efforts to forcibly assimilate Muslim minorities in the northwestern region of Xinjiang.

China’s strategy towards the Middle East is best characterised as that of a wary dragon: eager to engage commercially with the region and remain on good terms with all states in the Middle East, but most reluctant to deepen its engagement, including strengthening its diplomatic and security activities beyond the minimum required to make money and ensure energy flows.