During his visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia in 2013, China’s President Xi Jinping announced what would become his signature foreign policy programme, the Belt Road Initiative (BRI). With a planned estimated cost of $575 billion [1], the BRI focused on the allure of economic promise and progress: all countries have been invited to board the “express train” to wealth and prosperity.[2] The BRI was seen as the Chinese Marshall Plan designed to amass influence in Eurasia.[3]

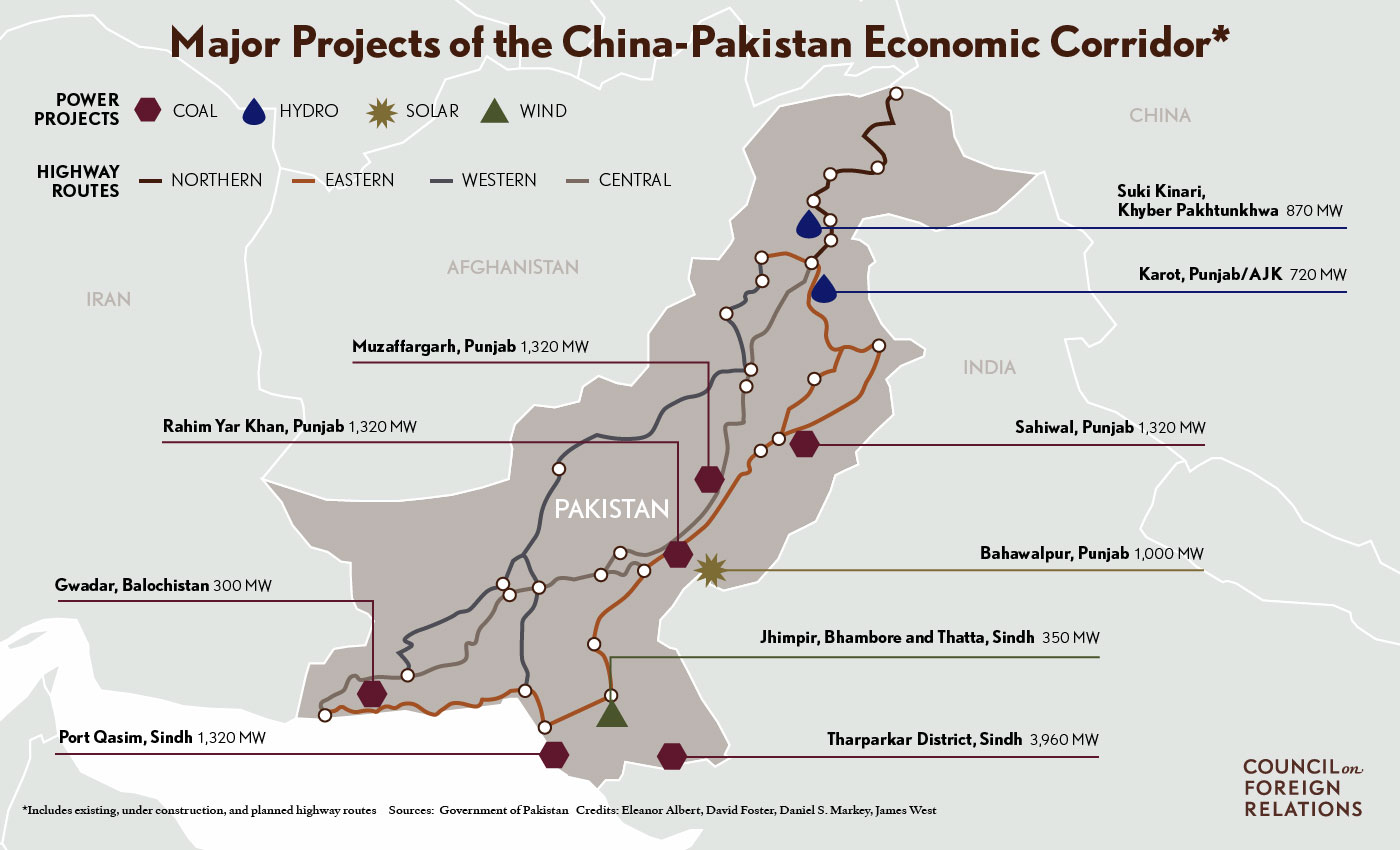

A component of this initiative is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). At $62 billion, this connectivity project was envisioned to stretch from the western Chinese city of Kashgar to Pakistan’s Arabian Sea port of Gwadar, located near Iran and Persian Gulf shipping lanes.[4]

For China, CPEC aims to provide China with an alternative trade route that avoids the maritime choke point of the Strait of Malacca and provides direct access to the Arabian Sea and beyond. Many Chinese writings argue that strategic competition can be carefully avoided by not encroaching in other states’ spheres of influence through these projects, with the US in particular.[5] The initiative is divided into three phases. The short-term phase (2015-2022) focusing on infrastructure, energy, and port development projects; the medium-term phase (2021-2025) which aims to establish 33 special economic zones (SEZs); and the long-term phase (2026-2030) which has yet to commence formally.

Currently, almost 80% of the China’s oil is currently transported from Strait of Malacca to Shanghai, (with a distance of almost 16,000km and transport time of to 2-3 months) – with CPEC planning to turn Gwadar into an operational port, the distance would be reduced to less than 5,000 km. Presently, the majority of fruit exports from the Baltistan region are being transported through air-cargo via Dubai. This would be significantly faster and cheaper if the same could be sent by road to China via Xinjiang with some estimates doubling revenue of trade in the region.

Pakistani officials predict that CPEC will result in the creation of upwards of 2.3 million jobs between 2015 and 2030. Energy infrastructure constructed by private consortia is expected to help alleviate Pakistan’s chronic energy shortages, which regularly amount to over 4,500MW. These shortages account for an estimated 2-2.5% lost from Pakistan’s annual GDP! For Pakistan, CPEC is not just meant to be 500 km worth of road and high speed rail networks spread across the country – but a plan and strategy that addresses Pakistan’s socio economic and political issues.[6]

CPEC was intended to achieve strategic goals for both the countries. For China, it’s to provide an alternate secure route to import energy and find new markets for its goods and services. For Pakistan, it is to help counter Indian influence in the region, position itself as a major transit point connecting Eurasian region with South Asia and provide a much needed base to kick start its economic growth.

Hype

Should the initial $46 billion worth of projects be implemented, the value of those projects would be roughly equivalent to all foreign direct investment in Pakistan since 1970 and would be equal to 17% of Pakistan’s 2015 gross domestic product. However, the external debt of Pakistan has surged significantly after accepting this Chinese offer.[7]

Even after CPEC investments, there are no signs of an economic turnaround but rather an increase in the likelihood of a default in foreign debt obligations. Pakistan’s external debt has risen to $100 billion, with a third owed to China at 7%-8% interest per annum. This is significantly more than what Pakistan owes the IMF at $7.6 billion.[9]

Even after CPEC investments, there are no signs of an economic turnaround but rather an increase in the likelihood of a default in foreign debt obligations

Locals in Pakistan have already felt the brunt of this economic turmoil. Food prices are up by 40% and transport costs by 20% over the previous year. The poverty rate in the country is forecast to reach an alarming 37.2%.[10] And for all the extra energy the CPEC projects have produced, many Pakistanis are struggling to afford the high electricity prices, just as high fuel prices keep people from travelling on the CPEC-built highways.

The highways have increased Chinese exports into the domestic Pakistani markets and has caused a major concern for Pakistan’s trade deficit as foreign automobiles, weapons, home appliances and agricultural products flood in. Many in Pakistan are worried that CPEC is a neo-colonial project that would give China control over Pakistan, like the British East India Company through which the British colonised the Indian Subcontinent. Others have conjectured that China will continue to leverage its debt to turn Pakistan into a client state and assume ownership over important assets.

From the 2.3 million jobs CPEC promised to create by 2030, by the end of 2022 it only managed to create 236,000 jobs out of which only 155,000 went to Pakistani workers. Four out of the nine approved SEEs are still under construction – five are yet to be launched. The Pak-China Friendship Hospital, meant to create a state-of-the-art medical facility in Gwadar, stands uncompleted by December 2022 with at least another year of delays. Moreover, in the energy sector, the 884MW Suki Kinari Hydropower Project was to be made operational by 2022. Unfortunately, the project is still only 70% complete. There are six other energy-related projects under construction, with no certain dates of completion. Of the transport infrastructure projects, only six are completed, five are under construction, and thirteen are yet to start. While these are some of the major projects that are long overdue, CPEC has faced numerous other disappointments. [11]

Corruption

Corruption in Pakistan has also hampered smooth progress. Delays, political instability and a financial crisis have all limited the implementation of CPEC projects over the past 10 years. When Imran Khan came to power in 2018, the brakes went on CPEC. The Khan government wasn’t convinced the deal was in Pakistan’s national interest and even alleged the then Chief Minister of Punjab province was taking kickbacks from Chinese companies working on CPEC projects.

The problems went beyond bribery. To look into the problems of the energy sector, the government in 2019 set up a committee to audit the power sector and examine the high cost of electricity. The report showed that six Chinese funded power projects had given huge profits to firms from China as compared to existing market rates.

According to the report, some of the power projects, where no bidding process was followed, are 237% more expensive than other similar projects in neighbouring countries like India. Similar wrongdoings were highlighted about two coal-based power plants also. It has been reported that $2.5-2.6 billion excess payments were made to Chinese firms. [12]

Effectively, Pakistani elites pushed forward poorly-negotiated projects based on electoral timelines without consideration for Pakistan’s ability to afford and leverage that newly installed capacity. As CPEC-related imports grew, Pakistan’s exports actually declined, thanks in part to the government’s pegging of the exchange rate.

Effectively, Pakistani elites pushed forward poorly-negotiated projects based on electoral timelines without consideration for Pakistan’s ability to afford and leverage that newly installed capacity

The combination resulted in uneven growth, a balance of payments crisis, and an imbalanced economic partnership. The privilege of Chinese FDI crowded out investors from other countries. Furthermore, Pakistani officials proposed poor solutions, such as creating a US zone within CPEC. Meanwhile, Pakistani officials, including in the army, came to realise that Beijing simply wouldn’t write off their debts. As arrears to Chinese electric power producers mounted, Beijing insisted that they be repaid — while also providing short-term emergency lending to Islamabad.[13]

Balochistan

CPEC has also exacerbated existing fault lines in society, leading to an increase in violence. Insecurity in Balochistan has grown to such a level that the Chinese and their instalments have become the target of frequent attacks by Baloch separatist outfits. The region is a wealth of minerals but this does not reflect in the impoverished lives of residents who struggle for basic minimum necessities, such as clean drinking water, reliable power supply, education and health facilities.

In 2018, insurgents from the Baloch Liberation Army attacked a Chinese consulate in Karachi, which was foiled by the police. Likewise, four members of the banned Baloch Liberation Army stormed the Pakistan Stock Exchange in 2020 where the Chinese have major investments. [14]

India, worried by Chinese expansionism and Pakistan’s progress has also decided to take matters into its own hands with strong evidence of espionage. In one instance, Indian spy Kulbushan Yadev from Balochistan, was arrested by Pakistani law enforcement agents within three hours of his border crossing from Iran. Yadev’s confessional statement vindicates Pakistan’s apprehension about Indian involvement in Pakistan, particularly in Balochistan. Yadev’s assignment was to disrupt CPEC and its related projects, specifically the Gwadar Port. [15]

Army Intervention

Amid mounting pressure from China over long delays in the completion of key projects, the Pakistan Army has taken control of CPEC with the appointment of retired three-star Pakistani Lt General Asim Saleem Bajwa overseeing its progress.

Supporters of the army, who maintain close ties with Beijing, exploited the dysfunction in prime minister Imran Khan’s government in 2019 to push legislation that gave it greater control over China’s infrastructure programme. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Authority bill carved out a new position to be held by a military officer to “…accelerate the pace…” of construction. Under the proposed law, the now disposed government ceded further ground to the military, which took over control of CPEC through a presidential ordinance that bypassed parliament. [16]

When the CPEC project was announced it was with grant fanfare. It was to be a new dawn for Pakistan. Modernisation, new infrastructure and jobs were the benefits that would flow. But CPEC has been stuttering and it’s questionable whether Pakistan will reap the benefits it believed in a decade ago. 10 years on, for many Pakistanis, the venture has been underwhelming.

[1] Belt and Road Initiative (worldbank.org)

[2] “Commentary: China’s ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative Delivering Benefits to the World,” Xinhua, April 15, 2017, available at <http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-04/15/c_136210956.htm>.

[3] Enda Curran, “China’s Marshall Plan,” Bloomberg, August 7, 2016; Theresa Fallon, “The New Silk Road: Xi Jinping’s Grand Strategy for Eurasia,” American Foreign Policy Interests 37 (2015), 142.

[4] The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: A View from the Ground | Wilson Center

[5] ChinaPerspectives-12.pdf (ndu.edu)

[6] pak-china-eco-corridor-deloittepk-noexp.pdf (theasiadialogue.com)

[7] Khan, Bilal (3 December 2015). “Pakistan’s economy is turning a corner”. Standard Charter Bank. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

[8] Khurram Husain (15 December 2016). “CPEC cost build-up”. Pakistan. Retrieved 30 December 2022

[10] China’s big gamble in Pakistan: A 10-year scorecard for CPEC | Lowy Institute

[11] Ten Years of CPEC: A Decade of Disappointments – South Asian Voices

[12] Pakistan: Govt report uncovers corruption in CPEC projects | ORF (orfonline.org)

[13] Pakistan tilts back to the West in multipolar era | Middle East Institute (mei.edu)

[14] Ten Years of CPEC: A Decade of Disappointments – South Asian Voices

[15] Dawn, 17 July 2019; Abbtakk 22 June 2017.

[16] Pakistan army muscles in on Belt and Road project | Financial Times (ft.com)