A decade ago, in September 2013 the One Belt, One Road initiative (OBOR) was launched in Kazakhstan by Xi Jinping. it was as audacious as it was geopolitical. The trillion-dollar global investment project planned to build roads, ports and other critical infrastructure around the world. For many it was a power play by China to shift the dominance of the western led global order, for others it was a chance of much needed investment.

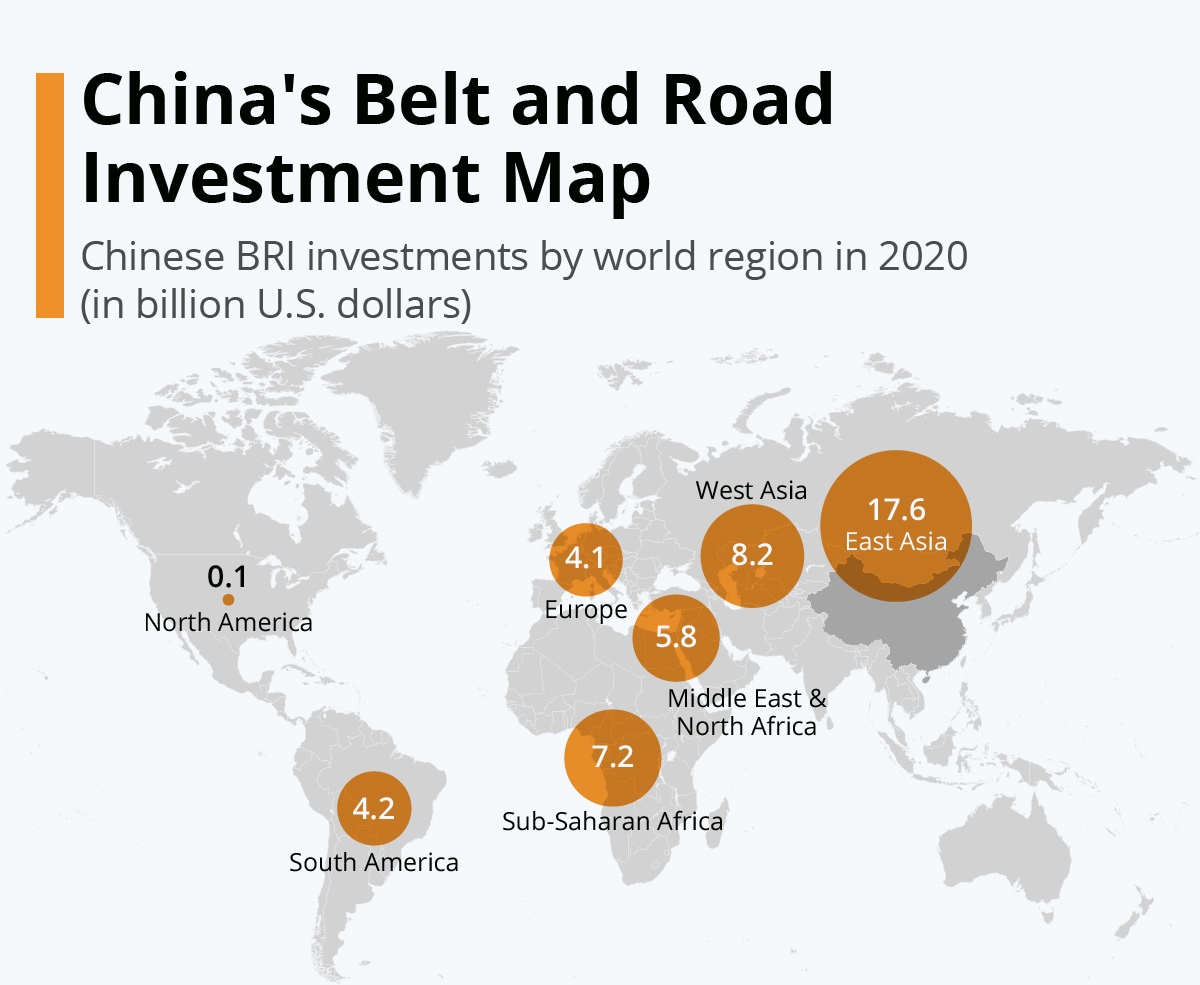

After a decade China has signed Memorandums-of-Understanding (MOUs) with 150 countries and 32 international organisations, among which 46 are in Africa, 37 in Asia, 27 in Europe, 11 in North America, 11 in the Pacific and eight in Latin America. China is now the world’s number one overseas investor. But it’s not all been plain sailing. Sri Lanka and the lease of the Hambantota port being saddled by the burden of unsustainable debt to China is well-documented. It has seen a raft of negative publicity. In 2018, former Malaysian President Mahathir Mohamad suspended work on certain Belt and Raid Initiative (BRI) ventures in his country over concerns of mounting debts to China. In Pakistan, too, the voices against the conditionalities tied to Chinese activities and loans have grown louder. India, for its part, had taken an early stance against the BRI and refused to participate in the inaugural Belt and Road Forum in 2017.

Context

Whilst the BRI has been seen by many as a global power play by China, but for China there was a context to the global project and it serves to solve a number of problems China was facing. China grew rapidly from 1979 to well into the 2000s. This was achieved with production and investment powered by the country’s integration into regional cross-border production networks. In 2002 China became the world’s biggest recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI) and by 2009 it had overtaken Germany to become the world’s biggest exporter. But the Great Recession from 2008 led to a decline in world trade, creating a major problem to the country’s export-oriented growth strategy.

The government attempted to counter the effects of declining external demand with a major investment programme financed by massive money creation and low interest rates. Investments included a massive state-supported construction boom, new roads, railways, airports, shopping centres and apartment complexes. Such a big construction push had left the country with excess facilities and infrastructure, highlighted by a growing number of ghost towns.

China’s leaders were not blind to the mounting economic difficulties. Limits to domestic construction were apparent, as was the danger that unused buildings and factories coupled with excess capacity in key industries could easily trigger widespread defaults. The party leadership then chose a new strategy, one that soughr to maintain the existing growth process by expanding it beyond China’s national borders: the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative was born, it would eventually become the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

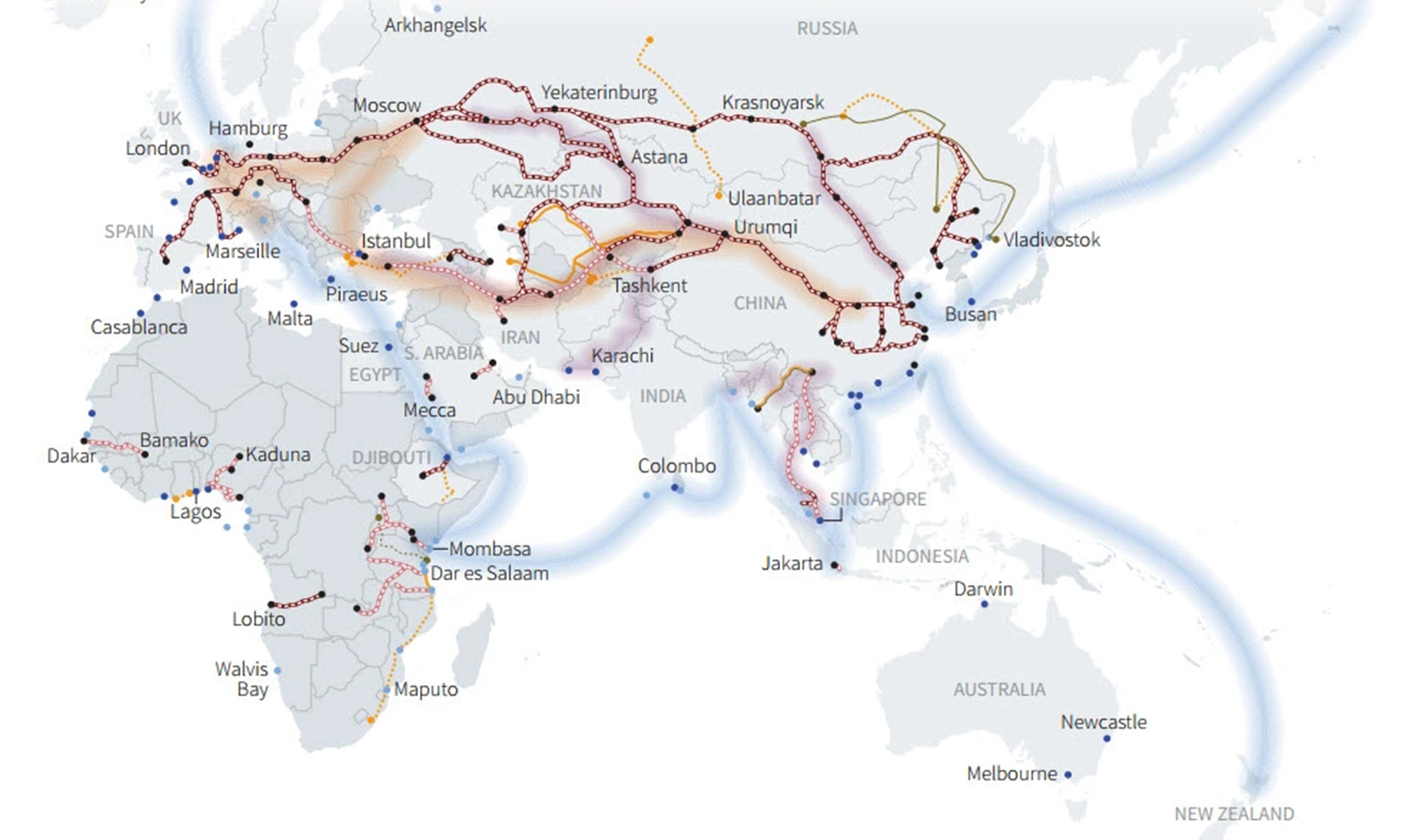

The initial aim of the BRI was to link China with 70 other countries across Asia, Africa, Europe, and Oceania. The two parts to the initial BRI vision: The “Belt” sought to recreate the old Silk Road land trade route, and the “Road,” which was not actually a road, but a series of ports creating a sea-based trade route spanning several oceans. The initiative was to be actualised through a number of separate but linked investments in large-scale gas and oil pipelines, roads, railroads and ports as well as connecting “economic corridors.”

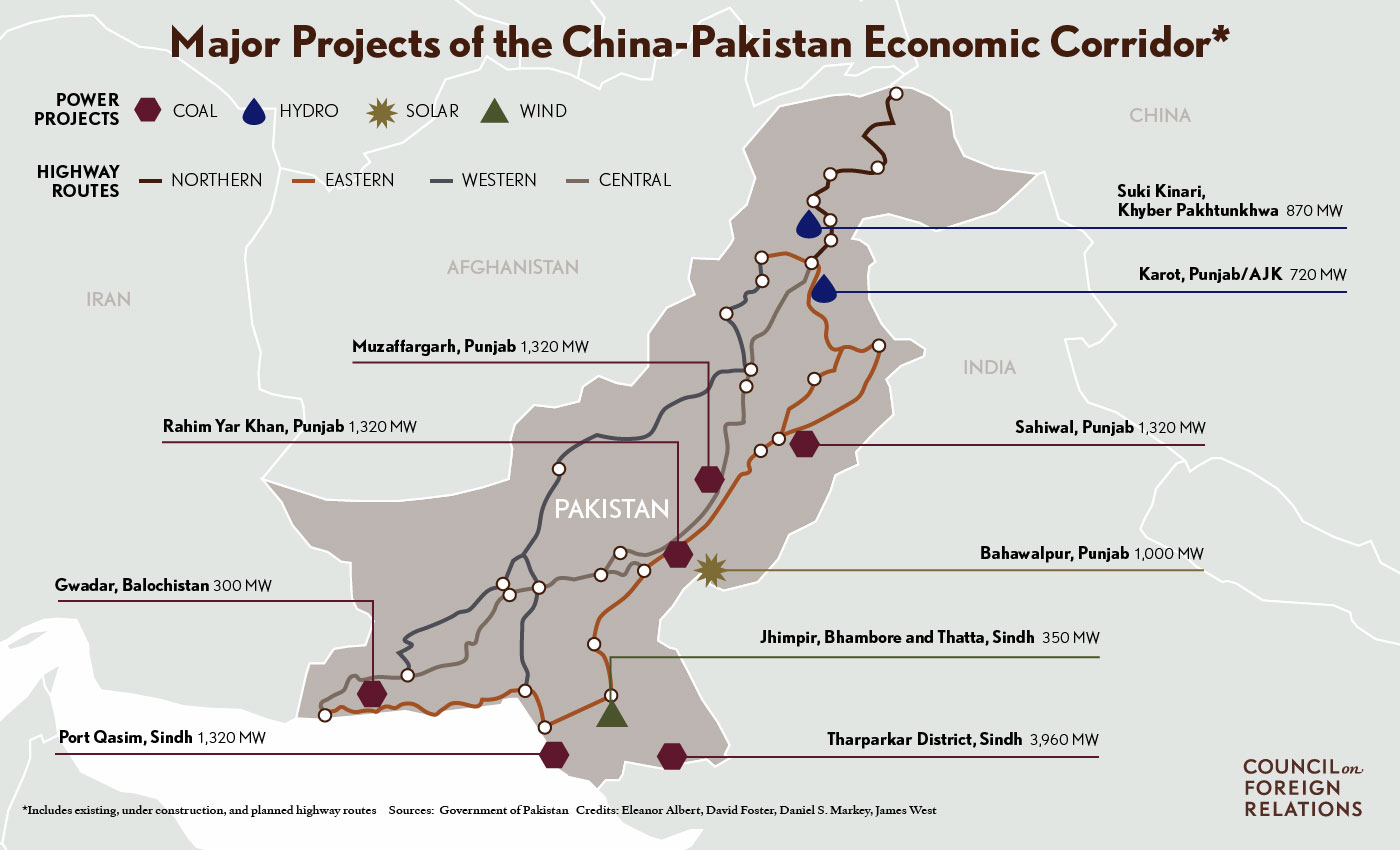

South Asia – China’s flagship BRI project is in Pakistan, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). CPEC projects are underway in the energy sector (which is the largest share of CPEC investment), transportation, infrastructure development and the creation of special economic zones to help facilitate industrial growth in the country. But the projects have been plagued with a number of security threats at different points in the country. In Balochistan where the Gwadar port is being built by China, separatist groups such as the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA) continue to threaten and execute attacks against both the Pakistan army and civilian Chinese workers. Despite progress in infrastructure projects the biggest concern has been the fact the prospect of Pakistan going into a severe financial crisis and debt spiral as the country does not have the capacity to repay the loans it has taken.

South-East Asia – Projects under the BRI projects in Myanmar and Thailand have been slow and often marked with delays due to protracted negotiations. In the case of Myanmar, several dormant or delayed mega-infrastructure projects received a boost during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Myanmar in early 2020. Xi called for “…both sides to deepen result-oriented Belt and Road cooperation and move from the conceptual stage to concrete planning and implementation.” The growing trade imbalance in favour of China is leading to concerns in Southeast Asia over China’s economic leverage in the region. There is wariness that economic dependence on China may affect the domestic economies and more importantly, the region’s independence and sovereignty.

Central Asia – Given its strategic location, Central Asia is critical to China’s BRI initiative. After the inception of the BRI, many projects involving Central Asian countries and China were signed in the fields of oil and gas pipelines, rail and road connectivity, trade promotion, industrial development, and mineral production. The BRI projects in Central Asia are marred by corruption, lack of transparency and debt problems. Almost 30% of the investments in Central Asia are lost in graft. The influx of Chinese workers for these infrastructure projects have minimised the opportunities for local employment. The increased influx of Chinese workers has led to violent protests in the region. In August 2019, more than 500 villagers in Kyrgyzstan entered a mine operated by a Chinese company and injured 20 workers. The steadily growing anti-China sentiments amongst the people of the region pose a serious challenge to the future of the BRI in Central Asia.

Pacific Island Nation’s – China has attempted to transform its bilateral relations with Australia, New Zealand and numerous Pacific island nations (PICs) into BRI projects. But tensions with Australia and New Zealand’s ban of Huawei after spying concerns emerged, has stalled the BRI in the region. The involvement of Australia, New Zealand, and the PICs in the BRI will depend on political negotiations, where caution, cost and attested benefits are to be weighed.

Africa – 45 out of Africa’s 54 countries have signed up to BRI projects. The investment has mainly been in the power, transport and communications sectors. But there have been major concerns that the infrastructure could turn into “white elephants”, too large, expensive, unviable, not well-planned and out of proportion with their value and usefulness. The assumption that every infrastructure project unlocks economic transformation, creates jobs, and fits into African countries’ national development plans may not be the case.

Latin America – In the first few years since it was conceived in 2013, the BRI did not include Latin America. This changed in 2018, when the Chinese Foreign Minister announced plans to extend the initiative to the region, at a meeting with the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States. Today, China is the second-largest trading partner and the third-largest investor in Latin America and the Caribbean. But Chinese investments have received environmental, social and governance concerns. In Mexico, a high-speed railway project deal was cancelled due to corruption allegations. Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and Colombia, the four largest economies in Latin America and accounting for around 70% of the region’s GDP, are yet to sign BRI agreements. At the same time, these four nations have comprehensive bilateral cooperation agreements with China and are host to multiple Chinese infrastructure projects. This raises an important question as to which projects can be classified as “BRI projects.” Álvaro Méndez, co-founder of the LSE Global South Unit, suggests “Not even China knows exactly what BRI is. Many things that already existed before BRI are being framed under it.” Over the last few years, there has been a noticeable decline in the funds allotted to Latin America under the BRI.

To date there is no official BRI map from China as the initiative has continued to evolve. In addition to infrastructure it now includes efforts at “financial integration,” “cooperation in science and technology,” cultural and academic exchanges,” and the establishment of trade “cooperation mechanisms.” Its geographic focus has also expanded. In September 2018, Venezuela announced that the country will now join China’s ambitious New Silk Road commercial plan, whilst China’s moves in the Arctic also now come under the BRI.

Under the BRI China has rushed to generate projects, many of which are not financially viable

Under the BRI China has rushed to generate projects, many of which are not financially viable. The European railway projects are illustrative of this. Chongqing-Duisburg, Yiwu-London, Yiwu-Madrid, Zhengzhou-Hamburg, Suzhou-Warsaw and Xi’an-Budapest are among the more than 40 routes that now connect China with Europe. Yet out of all these, only Chongqing-Duisburg, connecting China with Germany, was created out of a genuine commercial need. The other routes are political creations by Beijing. The Euro-China railways arrive in Europe full of laptops and other gadgets, the containers on the new routes come to Europe full of low-tech Chinese products, but they leave empty, as there’s little worth transporting by rail that Chinese consumers want. With only half the route effectively being used, the whole trip often loses money. Today, most of the BRI’s rail routes function only thanks to Chinese government subsidies.

As the years have gone by with the BRI a growing number of countries are becoming reluctant to participate because it means they will have to borrow funds for projects that may or may not benefit the country or generate the foreign exchange necessary to repay the loans.

After a decade China has definitely grown and expanded the BRI across the world. But it’s unlikely China will dominate the world as has been indicated by many. This is because US capital, multilateral institutions and European investors have more strength, prestige and networks worldwide than their Chinese counterparts. Western loans and investments are still preferred to China’s, whether in Europe, Africa or Asia. In addition, the US and its allies, such as the European Union (EU), Japan and South Korea, have technological strength, developed economies and sustainable infrastructure. Together, they offer a competitive advantage to China’s BRI and evidence that China’s economic presence has been exaggerated.

Similarly, the US-led economic order has deep roots around the globe. China’s endeavour to undercut this global system is unlikely to succeed. The Chinese cultural, social and economic system is not easily learnable and adoptable for many.

But the claims that the BRI will change the world and China’s aims of transforming its economic model have so far not succeeded. The BRI is not a miracle. It can’t transform places not yet on the verge of taking off. Nor has it and can it fully solve China’s domestic economic challenges.