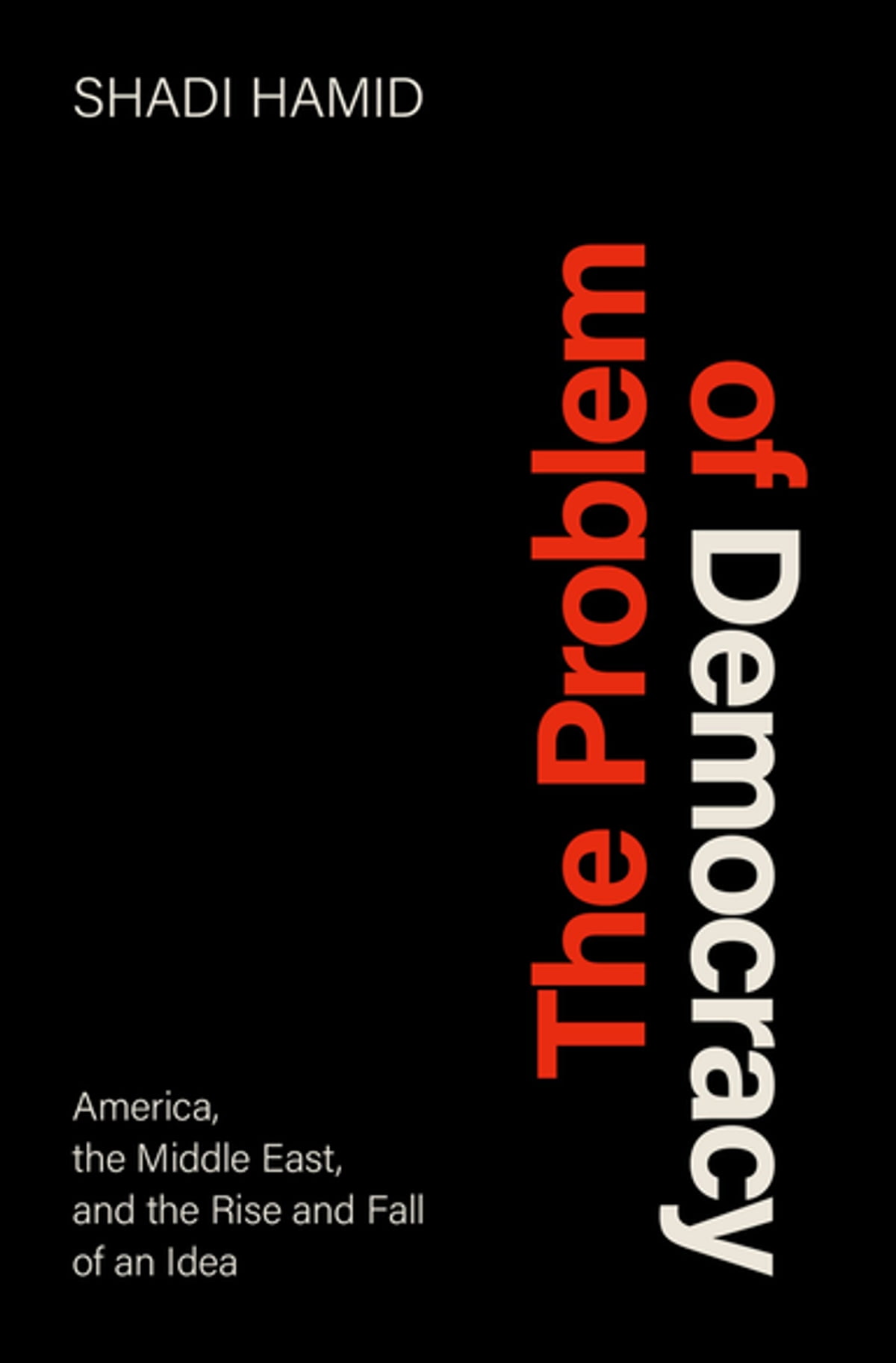

Book Review – The Problem of Democracy: America, the Middle East, and the Rise and Fall of an Idea

Shadi Hamid

January 2023

We are living in an age when economic failings have shaken faith in global capitalism while political failings have undermined trust in liberal democracy and even in the notion of what constitutes “truth”.

We are living in an age when economic failings have shaken faith in global capitalism while political failings have undermined trust in liberal democracy and even in the notion of what constitutes “truth”.

The shocking incidents of the 6th of January at US Capitol Hill in the aftermath of last presidential elections has led to much soul searching in mainstream western intellectual circles bemoaning the decline of democracy, grappling with policy suggestions to stem the tide.

Coming from authors right at the heart of the liberal establishment across the Atlantic, two books have stood out and merit attention – Financial Times, Martin Wolf’s, “The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism” and Shadi Hamid’s “The Problem of Democracy.”

Shadi Hamid, an Egyptian American political thinker and journalist, is a senior fellow at Brookings, a liberal think tank in DC and is best known for his previous provocative book “Islamic Exceptionalism: How the struggle for Islam is reshaping the world”. Shadi is a rising star in the American liberal establishment with close access to halls of power.

Hamids central theme in his book is in US foreign policy endeavours, especially in the Middle East. US policy makers have always been confronted by the democratic dilemma – how to continue being committed to democracy promotion when the outcomes are not “good” and conducive to achieving their foreign policy objective?.

When Islamist parties rise to power through free elections, the US has always preferred subservient dictators and go out of their way to undermine the outcomes of elections. With this legacy in mind and drawing on new interviews with top American officials, Shadi Hamid explores universal questions of morality, power, and hypocrisy. Why has the US failed so completely to live up to its own stated ideals in the Arab world? Is it possible for it to change?

Documenting instances of this dilemma, he cites the Arab spring of 2011 and especially the way it played out in Egypt. As a native, he gives a detailed insider account of how US policymakers were rhetorically all for democracy in Egypt, until the demonstrators chose an Islamist, Mohamed Morsi, as its president. The outcome of Egypt’s first free democratic elections alarmed Washington to such an extent that the US was happy to see Morsi toppled by the Egyptian military within 12 months. Barack Obama, who had spoken so eloquently at Cairo just a couple of years earlier, hymning the glories of democracy, refused even to call Morsi’s removal a coup.

In recent years, the US has faced the same dilemma elsewhere where free and fair elections handed power to politicians of the ultra-nationalist far right (e.g. Sweden and Italy). The result, in the Middle East at least, has been for the US to put democracy to one side and support unelected autocrats – so long as those dictators are happy to go along with US strategic priorities for the region.

Hamid’s answer to the dilemma is to separate democracy (the way a society makes its choices) from liberalism (an ideology with a worldview alien to Muslims and hence not Universal, though it remains his personal choice). He accepts that given a choice, Muslims will elect a government whose trajectory will not be liberal, aligned more with their Islamic aspirations, often at direct odds with US objectives and interests in the region, such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Shadi considers “Liberalism” as one choice an electorate can make using democracy but not necessarily the only one – “If democracy is a form of government, liberalism is a form of governing,…” he writes.

Building on this premise, Shadi Hamid proposes an agenda for reviving the lost art of democracy promotion in the Middle East. He develops this new theory of “democratic minimalism” (the central thesis of the book) in which liberalism and democracy are decoupled and procedural democracy becomes the primary goal.

While stressing his liberal commitments and being committed to human rights, individual liberty and gender equality, he suggests that the US should no longer combine these principles with democracy in the set of demands they make of other countries. Instead, Washington should require no more than “democratic minimalism”, asking only that the public get a fair say in who rules over them. In essence, US policymakers should drop the quest for liberal policy outcomes in previously undemocratic states.

There is negligible to zero chance of Hamid’s “democratic minimalism” becoming US policy any time soon. It’s hard to imagine any US President directing the US State department to support elections, even signing off aid and military packages, to countries where the outcome is certain to result in Islamic Governments acting on people’s universally popular demand. Just consider how such a government would deal with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict thereby threatening the survival of its most loyal ally in the region – Israel.

Hamid seems to understand this well and suggests the US keep its ironclad commitment to Israel intact, which Muslim countries with Islamist Governments will have to ultimately reconcile with. He seems to think when Islamists start seeing gains from Democracy in getting to power, they will themselves “democratize” while over time organically get incorporated into the global liberal order, which the US controls.

Shadi’s book raises more questions than it answers but also provides a good insight into a strand of thinking within the liberal US establishment on ways to incorporate “Islamist” polity within its order and promote democratic culture in the Middle East – which ultimately aims to further its Geopolitical interests in the region.

Overall Hamid is trying to come up with a strategy to save US credibility abroad and reconcile something US foreign policy regularly undermines. Maybe Hamid should have focussed on democracy more closer to home with confidence in democracy and mainstream politicians at historical lows.