News that a slew of new nations are considering joining the BRICS organisation has given a new lease of life to the organisation of developing nations. Egypt, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Argentina have either applied to join the BRICS, or are considering doing so. So should the western liberal order be worried?

In 2001, Goldman Sachs analyst Jim O’Neill came up with the term BRIC in order to refer to countries poised to drive growth in the 2000s. He came up with the BRIC for Brazil, Russia, India and China. The group adopted a capital ‘S’ when South Africa joined in 2010. At the time the countries had little in common beyond their economic futures. The BRICS were originally identified for the purpose of highlighting investment opportunities and had not been a formal intergovernmental organisation. Since 2009, they have increasingly formed into a more cohesive bloc with annual summits coordinating multilateral policies.

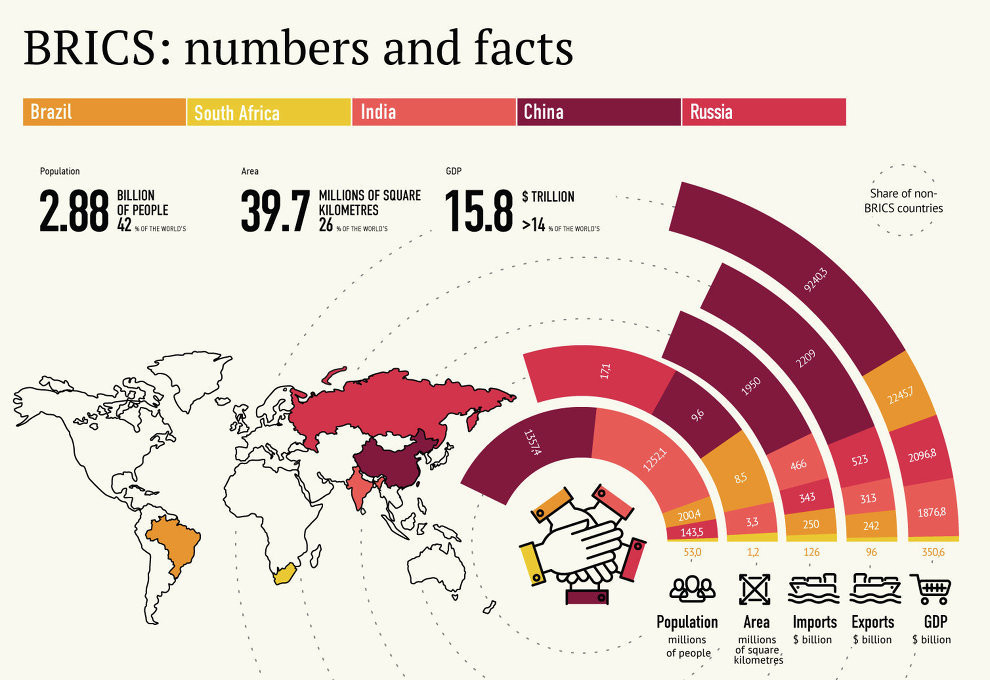

Today the five BRICS nations constitute about 42% of the global population, 30% of the world’s territory, 23% of global GDP and 18% of global trade. The BRICS are considered the foremost rival to the G7 bloc announcing competing initiatives such as the New Development Bank, Contingent Reserve Arrangement, BRICS payment system, and BRICS basket reserve currency.

As the years have gone by the BRICS nations made the most of presenting themselves as an alternative to the global order and many are excited at the prospect of a challenger to the western liberal order. The group has asked for certain changes to the global financial system. These include a call for the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to expand its use of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), which is used as a quasi currency to transfer funds between member governments. The BRICS has also called for a broad-based international reserve currency system.

Despite being called the world’s developing countries all the constituents of the bloc are different militarily, economically and socially as well as where they are in their respective stages of development.

Brazil has traditionally exported commodities and minerals to the US and Europe, but Chinese demand is changing the equation for Brazil’s agriculture. This has resulted in China becoming its number one import partner, which in turn has led to cheap Chinese goods flooding the Latin American nation at the expense of its own industries.

Russia is a largely commodities driven nation with extensive reserves of the world’s key minerals and resources. Russia is the largest global exporter of most of the commodities needed for industry. But with the invasion of Ukraine the nation has been placed in a perilous situation.

India, whilst still early in its development is a global leader as a provider of services. Unlike Brazil and Russia, which have built their economies on commodities exports India has transformed from an economy that was dominated by agriculture to one where the service sector generates half of the nation’s wealth. India for the moment has failed to become a mass manufacturer like the other BRICS countries and as a result still imports much of its manufactured goods from China.

China in a matter of decades has become the world’s factory, producing the world’s textiles and electronics. China is a global export powerhouse, but also a huge consumer of energy.

South Africa exports range from mining commodities, such as platinum, gold, diamonds and coal, to agriculture and manufactured goods. These are mainly to European markets. But South Africa is located far from global markets and there are other suppliers of South Africa’s main exports.

The BRICS have historically been united in their collective rebellion against the existing economic and financial order, but there are major differences within the bloc. China and India are at war in the Himalayas. The economic links between the BRICS members are also not of equal strength: Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa are all much more closely tied to China than they are to one another.

The relationship of each of the BRICS nations with the US, the world’s superpower, is strong enough and has acted as a wedge between most of the members with the others. Each nation also has its own bilateral relations with the US which weakens the bloc. What this bloc however does allow for is for each nation to deal with the others outside the international order, giving an appearance of a new coalition of nations standing apart from the US and the West. The new members who are all considering joining BRICS such as Egypt, Turkey and Saudi Arabia are very close to the US and could lead to the emergence of a faction within the BRICS, if they do ever join.

BRICS is always compared to the G7, but there is little these two have in common save the BRICS wants to be seen as an alternative to the western led G7 nations. The G7 is based upon western values of free markets, globalisation and national sovereignty. The BRICS nations have no such ideological alternative aside from they disagree with the values the G7 and the liberal order its based upon. They have for the moment not been able to present an ideological alternative.

On the political front the BRICS continue to criticise the western led order and propose an alternative currency, development and financial order. But the organisation is hampered by the fact that the five economies have very little to do with one another, with little commonality of purpose. While China and Russia would both like the BRICS to become the anti-G7 that rallies the emerging world in opposition to the “hegemonic” West, both India’s Narendra Modi and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa flitted from their screen-based BRICS summit in June 2022 to the Bavarian Alps to participate as observers at the G7 summit. For Modi, it was his third G7 summit, which he sees as testimony to India’s status as a great power.

The G7 has moved to place a wide spectrum of sanctions on a major BRICS member, Russia. The BRICS response was Brazil voting to condemn Russia’s attack on Ukraine at a UN vote in March 2022, the other BRICS members stalled for time and avoided choosing sides. They have taken advantage of Russia’s willingness to do business, while staying open to Western trade and investment. India has increased purchases of Russian energy, but it also attended the G7 and restarted trade talks with the EU. South Africa typically aligns with Russia, but it too attended the G7, where it discussed energy projects with Germany. In reality the BRICS nations were unable to help or stand as a bloc to the western led G7.

For the moment BRICS remains a platform for powers such as China, Russia and India to satisfy and increase their commercial interests, through any means necessary regardless of diverse political interests that each of them possesses. The fact that there is no formal application process to join BRICS, aside from receiving unanimous backing from all existing BRICS members, is very telling that the BRICS is a loose and informal gathering of developing nations, despite the rhetoric.