Five of the world’s nuclear powers agreed last week that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought” in a rare joint pledge to reduce the risk of such a conflict ever starting. The pledge was signed by the P5 – USA, Russia, China, the UK and France; the main five nuclear weapons states. The release of the statement was timed to coincide with the five-yearly review conference of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), where back in 1968 the nations with nuclear capabilities bargained with nations without nuclear weapons, that they would disarm so long as the rest of the world did not acquire nuclear weapons.

Nuclear weapons can kill a large number of people and cause great damage to buildings and structures. The nations who have acquired nuclear capability have spent large sums of money for a weapon they are unlikely to use in wars. The envisioned utility of nuclear weapons was to deter aggression. However, the potential for massive devastation forces nations to rethink using them as a weapon of war as the destruction is indiscriminate and extremely disproportionate to conventional warfare.

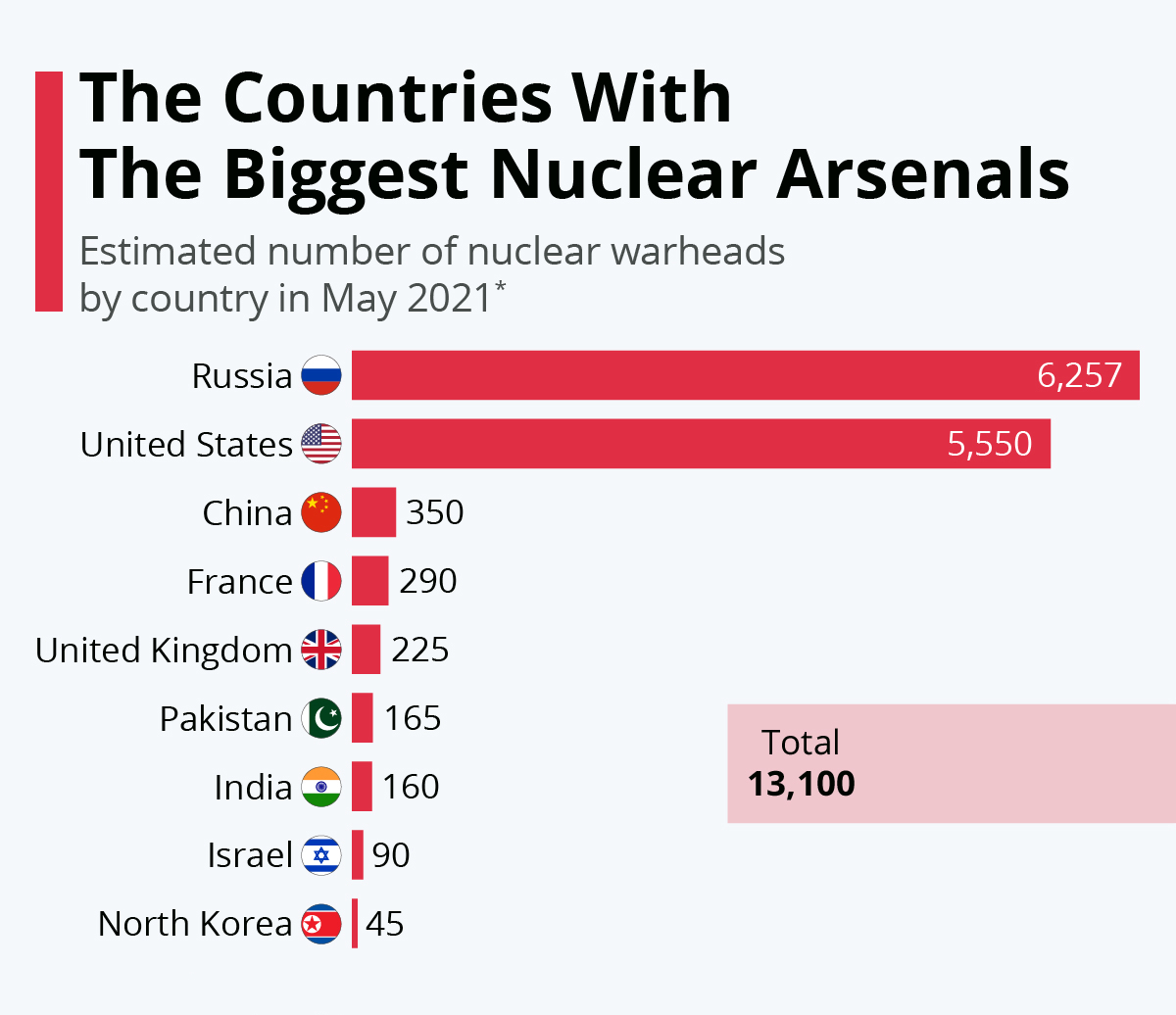

Nine countries today have nuclear weapons with a variety of delivery systems. There is a distinction between deployed and non-deployed weapon systems. Deployed weapons are already integrated with a delivery system and ready to use. Warheads in non-deployed or reserve status still require this final step before they can be delivered.

The most advanced delivery systems are the nuclear triad system. These are land-based missiles, submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBM) and weapons carried by aircraft. Land-based ballistic missiles—especially intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) – provide long-range strike capability. SLBMs have retaliation capabilities in the event that a country’s land-based systems are destroyed in a first strike, whilst warheads on an aircraft provide cover, but they are slower to reach their target than missiles. Each nuclear nation has a different mix of delivery capabilities, only the US, Russia and China are considered to definitely possess a full triad.

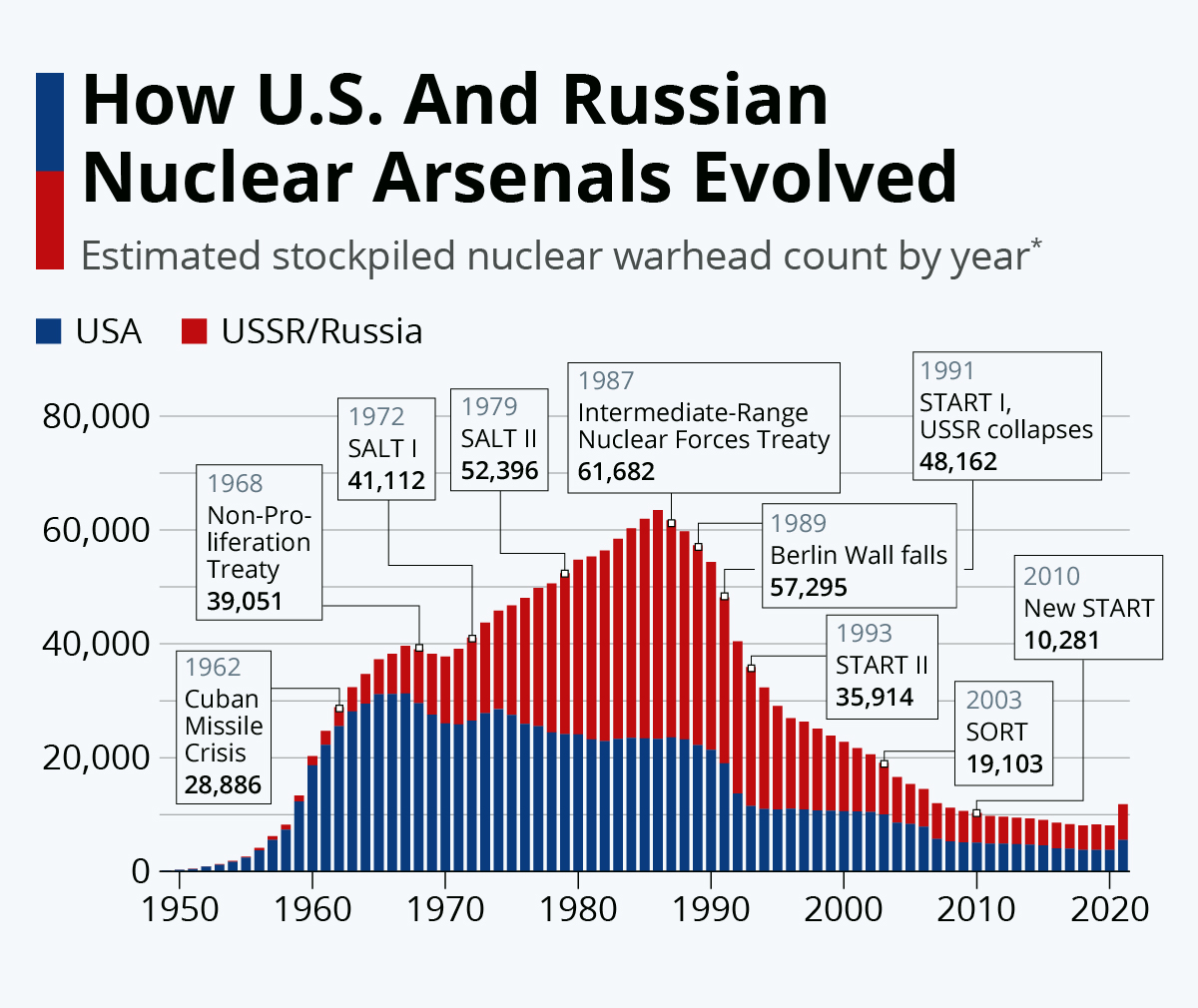

Nearly 90% of global nuclear weapons are held by the US and Russia. The US has around 5,550 warheads, and Russia has 6,257. These include both strategic warheads (which can strike sites located far from any battlefield) and non-strategic, or tactical, warheads (which are intended to be used near a battlefield, and are usually less powerful). The current size of these arsenals pales in comparison to each country’s peak inventory during the Cold War. The USA had 31,255 in 1967 and the Soviet Union had 40,159 in 1986.

Throughout the Cold War, the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) required a large force that would allow for a massive retaliation even if a first strike eliminated a large portion of a country’s nuclear arsenal. Additionally, during most of the Cold War, delivery systems were not particularly accurate, which required that nuclear weapons have very large yields to reliably strike a target that might be located miles away from the point of detonation. As the accuracy of delivery systems improved, fewer nuclear warheads were required to maintain a credible deterrence threat, leading to a decline in the arsenals if the US and the Soviet Union

Several countries had nuclear weapons programmes that were later abandoned. This was due to changes in political circumstances that reduced the need for nuclear weapons. In some cases, it was due to pressure from a major power that provided a guarantee under its own nuclear umbrella.

Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine all inherited nuclear weapons when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991. Ukraine was for a short period the third-largest nuclear power in the world. All three countries returned the weapons to Russia by the mid-1990s to be dismantled.

South Africa independently developed her nuclear weapons and subsequently forfeited them. The pro-apartheid government from the 1960s to the 1980s produced six nuclear weapons. In 1989, the programme was stopped as apartheid came to an end and the government of FW de Klerk handed power over to the African National Congress (ANC).

Argentina and Brazil also abandoned their nuclear programmes before developing a nuclear device. They both secretly pursued nuclear weapons in the 1960s. By the early 1990s, both countries gave up their weapons programmes and signed the NPT.

South Korea and Taiwan also had secret nuclear programmes in the 1970s. Both programmes were subsequently disbanded—South Korea’s in 1975 when she signed the NPT and Taiwan’s in 1988 as a result of diplomatic pressure from the US. In the Middle East, Iraq, Syria and Libya all had active nuclear weapons programmes. Iraq’s nuclear programme was forcibly dismantled after the Gulf War, and Libya gave up her nuclear programme in 2003. Syria’s nuclear ambitions never progressed far, but she is believed to have possessed enriched uranium and built a research reactor with the aid of North Korea. In 2007, Israel took out Syria’s reactor with airstrikes.

Modernisation

Despite all the talk of reducing nuclear stockpiles and disarmament, the nuclear arms race never really finished and remains in full swing. Beatrice Fihn, executive director of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), said the words of the five countries do not match their actions. “They write this ‘nice’ statement but doing exactly the opposite in reality. They’re in a nuclear arms race, expanding nuclear arsenals, spending billions on modernising and constantly prepared to start a nuclear war.”[1]

In the USA’s last nuclear posture review in 2018 she emphasised the modernisation of the entire nuclear arsenal including the increase in the types and role of US nuclear weapons. This also includes the pursuit of a nuclear-armed submarine launched cruise missile to provide a nonstrategic presence.

Russia has been replacing her ageing Soviet-era ICBMs, SLBMs and ballistic missile submarines. Alongside this, Russia is developing several kinds of nuclear delivery vehicles. Some of these, like the Sarmat ICBM, replicate capabilities that already exist. Others expand the force with new types of delivery systems. President Putin unveiled most of these systems during his 1st March 2018, annual State of the Nation address to the Federal Assembly, in which he presented a range of weapons systems currently under development in Russia. His speech also featured videos and animations of new weapons systems.[2]

The US has recently made a big issue of China’s expanding nuclear weapons. Much of this is misplaced as China historically had a small and mostly land-based nuclear arsenal. With her growing power and the need to be taken seriously globally, China is building more road-mobile ICBMs and strategic nuclear submarines as well as introducing air-based nuclear capabilities. Whilst the US has 4,480 nuclear warheads, China remains at 350 warheads and will not be catching up with the US anytime soon.

The UK in 2021 outlined the government’s review of security and defence policy, Global Britain in a Competitive Age: The Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy and announced that she was increasing the cap on her nuclear stockpile from 225 to 260 warheads. The government explained that the decision to increase her nuclear stockpile for the first time in decades was due to a worsening strategic landscape and technological threats.

Similarly France has launched the development of her third generation of nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines and the broad renewal of her nuclear forces.

Despite the talk of reducing and eliminating nuclear weapons, the reality is all the global powers are expanding their nuclear programmes in order to maintain an image of strength and deter others. This has remained the case since the 1968 NPT treaty and will continue into the future as global competition has always driven the acquisition of nuclear weapons. Despite nuclear weapons being a special class of weapon, the reality is all weapons of war are nothing without a strategy and there is no strategy without politics. This is why nuclear weapons – a weapon of war, is politics through other means.

[1] China, US, UK, France and Russia pledge to avoid nuclear war – CNN (ampproject.org)

[2] Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly • President of Russia (kremlin.ru)