US president Donald Trump is now the third president dealing with the Afghan war. After an election campaign which saw him reiterate US withdrawal from global conflicts, US president Donald Trump did his latest U-turn on August 21st by unveiling his long-awaited Afghanistan strategy.[1] The Afghanistan war, now officially America’s longest ever war, has divided his own administration and seen a number of advisors relieved of their posts. President Donald Trump reaffirmed his commitment to Afghanistan in his August 21st address to the nation. His speech highlighted the familiar challenges associated with the Afghan theatre, but the US president accused Pakistan for its role in America’s failure and Trump highlighted his realization that a hasty withdrawal of troops could have dire consequences. At the center of his strategy was a vague policy on troop numbers and deployments all pointing towards conflict management as opposed to conflict resolution.

When the US invaded Afghanistan back in 2001 its plan was to drive the Taliban from power and lay the foundations for a democratic Afghanistan. The political architecture the US created was to keep Afghanistan from again becoming a launch pad for any Jihadis and firmly within America’s sphere of control. A democratic Afghanistan was quickly abandoned when the Taliban insurgency was in full swing. But today, 16 years later and two general elections later the government in Kabul has scarcely any influence over the rest of the country. When the pro-Russian regime fell in 1992, the numerous factions that fought the Soviets from 1979 – 1989 turned their guns on each other, the Taliban emerged victorious from this in 1996. After the US toppled the Taliban regime after 9/11, it brought those old warlords together to form a regime. The US established a government on a patchwork of warlords who only had local or regional influence. The only thing that bound the warlords together was their hatred for the Taliban. The Kabul central government has muddled through the years of the Hamid Karzai presidency but it has no capability beyond its government offices to shape the country. The core of Trumps strategy is based on the idea that US support for Afghanistan is not unlimited and that Washington should not be engaged in nation-building in the country.

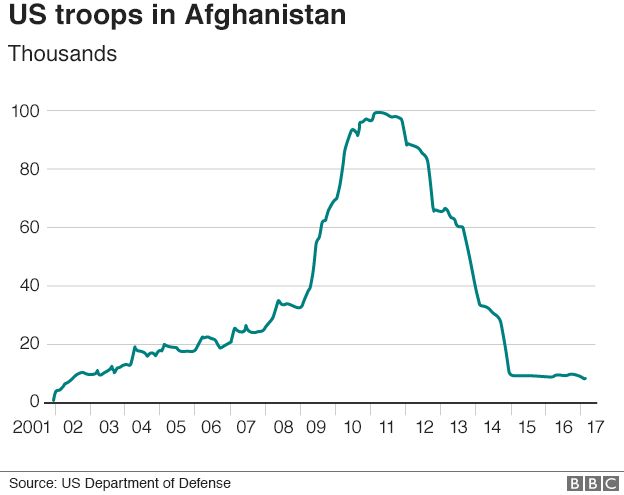

President Trump praised the Afghan government and its security forces, but it’s clear to all that the security services whether the armed forces or domestic police are in no position to maintain order in the country. Prior to Trump, Obama’s strategy was to surge the troops and then withdraw them before his re-election. Trump has been arguing for some time of an extremely small footprint of US military personnel, but in 2011, the US had nearly 100,000 troops in Afghanistan, along with almost 10,000 British troops and 30,000 additional NATO personnel. But even this wasn’t enough to defeat the Taliban insurgency, or even force the group — or its increasingly fractured leadership — to enter meaningful negotiations. The US strategy of handing security over to Afghanistan’s military and security services, will in all likelihood see the Taliban take over the remaining 50% of the country they currently do not have. The Afghan armed forces suffer from a major problem: too many generals. The military has more than a thousand Generals, which arose from top figures from so many different factions being incorporated into the security system to keep the peace. But instead of advancing the national interest and fighting the Taliban, most of these generals are focused on advancing their own personal interests. Trumps strategy of managing Afghanistan will in all likelihood fail, like his predecessors, as the security services are in no position to secure the country.

Despite these challenges the US from the day it invaded Afghanistan has never deployed the resources to resolve the conflict in Afghanistan due to political considerations back home. The US commenced operations barely 30 days after Sept. 11, which was not enough time to mount an invasion using US troops as the primary instrument. Rather, the US made arrangements with factions that were opposed to the Taliban and defeated in the Afghan civil war from 1992 – 2001. This included organizations such as the Northern Alliance, Shi’ah groups from the Hazarah community. These groups supported the US out of hostility to the Taliban and also due to substantial bribes paid by the US. The overwhelming majority of ground forces opposing the Taliban in 2001 were Afghan. The US inserted special operations forces teams to work with these groups and to identify targets for US airpower. The US then got busy with the Iraq war in 2003 and then began to bleed with the insurgency from 2005 onwards. This allowed the Taliban to regroup and reorganise and by the time Barack Obama came to office in 2009 the Taliban had regained a lot of what it lost in 2001. Obama saw the best way to achieve US operational goals was to massively increase the military footprint, with an aggressive deadline for withdrawal. This led to tension between his administration and the military as the military could not defeat the Taliban insurgency with the number of troops in such tight deadlines. The most high-profile victim of tensions between Obama and the military was General Stanley McChrystal who was relieved by Obama of his command due to his scornful remarks about Obama’s strategy.[3] Trumps strategy of adding a few thousand troops to a conflict that over 100,000 troops could not win in 16 years shows conflict resolution is not the aim.

Despite Trumps rhetoric about Afghanistan he has presented a strategy for Afghanistan not fundamentally different to his predecessors. He plans to continue the conflict, his plan is to work in some form or shape with the Kabul government and train Afghan security forces to maintain some semblance of security. Like his predecessors he plans to achieve this with minimal resources and troops. Trump revealed in his speech on August 21st how he plans to manage the Afghan theatre. His remarks on India and Pakistan reveal the surrounding nations are how the US plans to maintain Afghanistan, this also includes China, Iran as well as Russia. These countries despite their own interests are viewed by the US as the ideal way to manage Afghanistan, with minimal US resources and troops. The role of these nations in Afghanistan and how the US plans to achieve its strategic goals through them will be analysed in a upcoming RO series on Afghanistan.

If the US is not looking to win the conflict in Afghanistan outright, this naturally raises the question of why this is the case and what this achieves for the US. This will be analysed in the upcoming RO series on Afghanistan, but one Geopolitical analyst gave an interesting insight: “The US has had the ultimate aim of preventing the emergence of any major power in Eurasia . The paradox however is as follows – the goals of these interventions was never to achieve something – whatever the political rhetoric might have said – but to prevent something. The United States wanted to prevent stability in areas where another power might emerge. Its goal was not to stabilize but to destabilize, and this explains how the United States responded to the Islamic earthquake. It wanted to prevent a large, powerful Islamic state from emerging. Rhetoric aside the United States has no overriding interest in peace in Eurasia. The United States also has no interest in winning the war outright……the purpose of these conflicts is simply to block a power or destabilize the region, not to impose order.”[3]

Part 1 – The US Failure in Afghanistan

Part 2 – Managing Afghanistan

Part 3 – The Geopolitics of Afghanistan

Part 4 – Managing Afghanistan Through Pakistan

Part 5 – Managing Afghanistan Through Iran and India

Part 6 – Managing Afghanistan Through China and Russia

Part 7 – Managing Afghanistan Through the Taliban

[1] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-41007995

[2] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/10395402

[3] Friedman, G, ‘The next 100 years,’ a forecast for the 21st Century, 2009

One comment

Hassan

3rd September 2022 at 6:06 pm

SO insightful the article and the special report. Old but it held the test of time.Hoping for more content, epecially regarding Middle East.