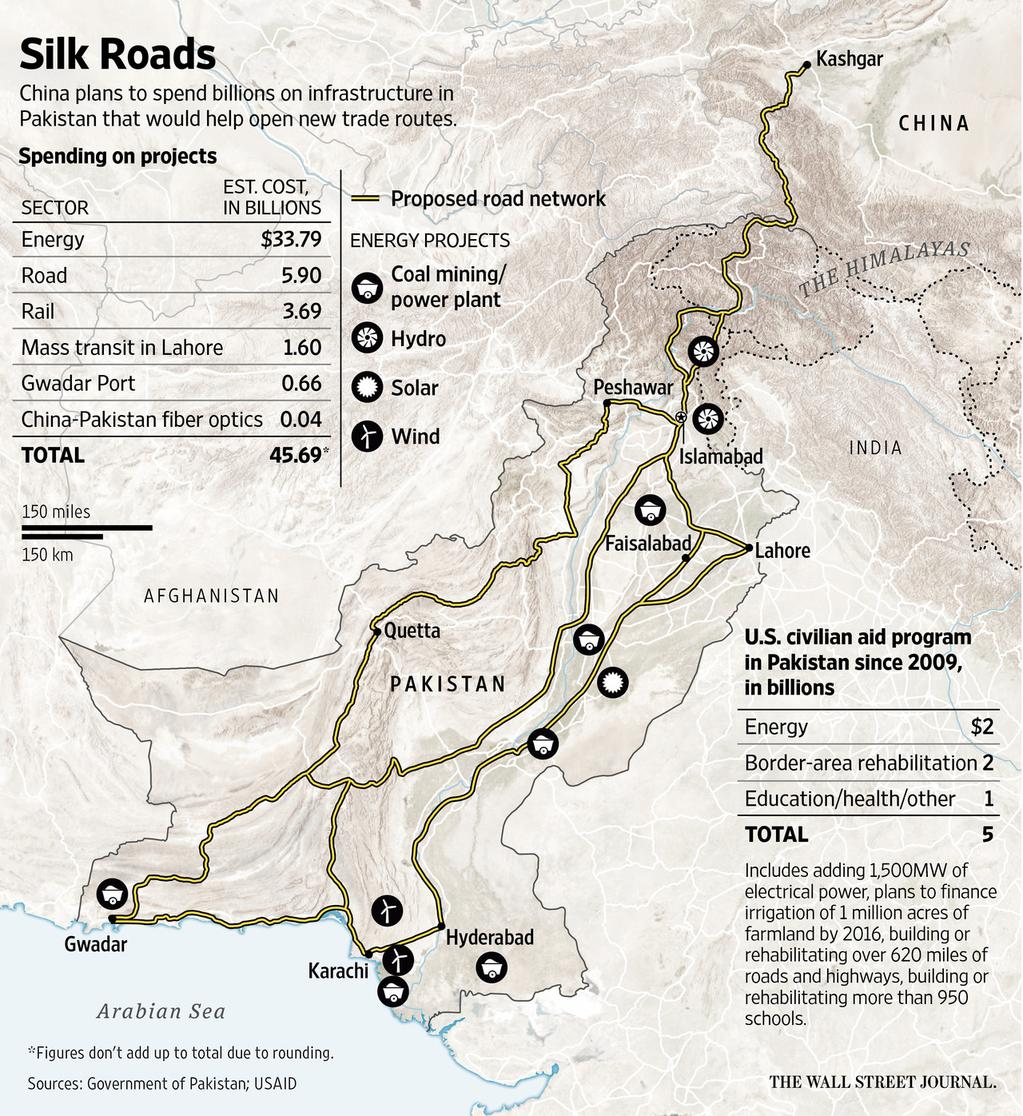

On the 20th of April the Government of China officially committed itself to $46 billion in large-scale spending in Pakistan, primarily in capital infrastructure and energy projects.[1] The first phase of this initiative was finalized in the form of 51 different energy and infrastructure agreements, collectively valued at $28 billion. To signify the importance of this program to China, China’s president, Xi Jinping, visited Pakistan on an official state visit to oversee the finalization of each program. The investment is an instrumental component of China’s “One Belt, One Road” plan to connect its Muslim-majority northwestern province of Xinjiang to the Arabian Sea via Gwadar, a nascent port city in Pakistan’s Baluchistan province. Although a significant initiative by any measure, China’s move into Pakistan is not driven by ambition (such as directly competing with the US for influence in the region), but by a desire to mitigate specific – but emerging – security risks and to exploit under-realized economic opportunities. The net effects may ultimately benefit the US Regional Security and Stability

A primary driver behind China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative is to instill stability across the regional strip comprising of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Xinjiang. To China, the mounting security concerns stemming from Afghanistan and Pakistan present a direct threat to its capacity to maintain a firm hold over Xinjiang, a geographically large Muslim-majority province that forms China’s northwest bridge to Central Asia and West Asia. In the face of its own transgressions against the people of Xinjiang, Beijing has a strong incentive of mitigating the external risks that could fuel an armed uprising in that province. Those risks emanate from Afghanistan and Pakistan in the form of foreign fighters and armed groups. In the case of Afghanistan, the Chinese offered to play a role in facilitating peace talks between the Taliban and Afghan government.[2] Beijing is also thought to have pressured Pakistan into not detracting from America’s post-withdrawal strategy. Both are a significant departure from China’s previous strategy concerning Afghanistan whereby Beijing pushed for a swift US exit, but the prospect of mounting Uighur-resistance in Xinjiang has pushed it to intersect with Washington on this issue.

China’s investments in Pakistan will serve to better connect China to Afghanistan, and in the process, Central and West Asia. With Pakistan as its conduit, the “One Belt, One Road” program will allow Chinese manufacturers, exporters and investors to yield largely untapped economic opportunities in vast and mostly underdeveloped regions. This economic dimension is dependent on stability within Afghanistan, which in turn means the strengthening of the Afghan government and state, at least in regards to the threat posed by the Taliban and other armed groups. Although the “One Belt, One Road” initiative positions Pakistan as an indispensable conduit for China (without whom China would not have access to the Arabian Sea or West Asia), it will also require Pakistan to play the leading role in maintaining the One Road’s security. During President Xi Jinping’s visit, the Pakistan Army announced that it would establish a 10,000-strong “Special Security Division” composed mostly of elite soldiers from its Special Services Group (SSG) to protect Chinese personnel involved in One Road infrastructure projects. This figure does not include the costs of protecting the actual infrastructure itself, which is essentially a vast network of transport systems spread throughout Baluchistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan’s western provinces.

Although one might be tempted to assume that China’s investment is a play to counterbalance India by strengthening Pakistan, the actual effect of the program will require Pakistan to continue focusing on internal security issues. For one thing, it will be upon Pakistan to guarantee that fighters, armed groups and weapons do not flow to Xinjiang through Pakistan’s Tribal Areas. Knowing the reality of the Tribal Areas thus far and the impact it has had on Pakistan as a result of America’s ongoing occupation of Afghanistan, it is clear that the task of protecting China’s investments will not leave Pakistan with much room to focus on India. This reality closely aligns with Washington’s desire to see Pakistan continue committing towards ‘internal threats’ (which are, ironically, defined by external powers such as the US and China). In this regard Pakistan has begun to further modernize its counter-insurgency capacity through the acquisition of next-generation AH-1Z “Viper” attack helicopters from the U.S and armed unmanned aerial vehicles or drones such as the Burraq. That said, the Chinese are reportedly willing to strengthen specific elements of Pakistan’s externally-focused assets. Beijing is reportedly in the final stages of securing a multi-billion dollar sale of 8 new submarines (possibly based on the Type-041 ‘Yuan’ design) to the Pakistan Navy. China is also supporting Pakistan in its ongoing fighter modernization efforts via the JF-17 and may potentially expand the scope to include the J-31 Gyrfalcon, a 5th-generation stealth fighter currently under development.

a play to counterbalance India by strengthening Pakistan, the actual effect of the program will require Pakistan to continue focusing on internal security issues. For one thing, it will be upon Pakistan to guarantee that fighters, armed groups and weapons do not flow to Xinjiang through Pakistan’s Tribal Areas. Knowing the reality of the Tribal Areas thus far and the impact it has had on Pakistan as a result of America’s ongoing occupation of Afghanistan, it is clear that the task of protecting China’s investments will not leave Pakistan with much room to focus on India. This reality closely aligns with Washington’s desire to see Pakistan continue committing towards ‘internal threats’ (which are, ironically, defined by external powers such as the US and China). In this regard Pakistan has begun to further modernize its counter-insurgency capacity through the acquisition of next-generation AH-1Z “Viper” attack helicopters from the U.S and armed unmanned aerial vehicles or drones such as the Burraq. That said, the Chinese are reportedly willing to strengthen specific elements of Pakistan’s externally-focused assets. Beijing is reportedly in the final stages of securing a multi-billion dollar sale of 8 new submarines (possibly based on the Type-041 ‘Yuan’ design) to the Pakistan Navy. China is also supporting Pakistan in its ongoing fighter modernization efforts via the JF-17 and may potentially expand the scope to include the J-31 Gyrfalcon, a 5th-generation stealth fighter currently under development.

However, given the reality of Pakistan’s economic constraints and the willingness of its political and military leadership to align Islamabad’s policies with those of Washington, it is unlikely that any of these modernization programs will reach the threshold of decisively altering the balance of military power in South Asia against India’s favour. At most, these programs will allow Pakistan to continue maintaining its doctrine of “minimum deterrence”, i.e. a base minimum necessary for it to defend itself from an external foe, and the US seems content with allowing China to meet Pakistan’s needs up to that level.

Ultimately, China’s “One Road, One Belt” initiative is driven by immediate security and economic interests within its regional sphere, particularly in regards to Xinjiang. Moreover, it is apparent that this initiative intersects with numerous key American interests in regards to Pakistan, namely Islamabad’s continued focus on “internal threats” and neutralization of armed groups within Afghanistan and Pakistan, which – in China’s hopes – would damper armed dissent in Xinjiang.