By Bilal Khan

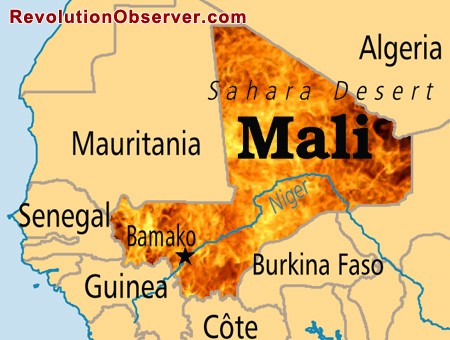

The French-led intervention in Mali is being framed by Western-governments (specifically those of France, the U.S, Britain and Canada) as a legitimate mission to subvert the threat of Islamists in Mali.[1] However, before accepting this as proof of goodwill on the part of the West towards the people of Mali, one must be mindful of the indicators that strongly suggest otherwise.

This offensive is by design an effort to support the Government of Mali, a regime that had overthrown an elected government through a military coup in 2012, and thus, does not represent the people.[1] Furthermore, emerging allegations of attacks against civilians by the government’s forces indicate that this regime is a clear threat to the public.[2] As the intervention progressed with rebels abandoning the areas they had previously captured, alleged instances of Mali’s military engaging in torture and unlawful executions, shelling against Tuareg civilians, and deliberate attacks against Tuareg livelihoods (i.e. cattle and livestock) have followed.[3] It is worrying that Western governments would be frantic about reports of so-called Islamist oppression in Mali[4], yet support another threatening and corrupt entity in the country.

This approach is not exceptional for Western governments, particularly the French government in relation to Africa. The French government has militarily intervened in the continent more than 40 times since the end of the Second World War.[5] This history is fraught with examples of atrocities, political interference, and a desire to ensure France’s strategic economic and security interests. For example, in 1992 leaders of the Algerian military cancelled the country’s elections driven by the fear that an Islamic political party would win. In the resulting civil war, the French government supplied the dictatorship with helicopters and weapons.[6] In fact, as recent as the dawn of the popular uprisings across the Middle East, the Sarkozy government provided its unequivocal support of the dictator Zine el-Abidine bin Ali against the Tunisian people.[7] With such examples, there is little room to assume goodwill.

Instead, there is greater suspect that France’s actions in Mali are strongly driven by its desire to guarantee its own security and economic interests, above those of Mali itself. One analyst states, “it would be rather simplistic and naïve to accept the position that France’s intervention is motivated by a desire to do good for the best interests of the Malians.”[8] This point is in reference to the fact that France relies on energy resources, i.e. oil and uranium, from Niger, Mali’s next-door neighbour.[9] There are reports of France deploying special-forces units in Niger to protect these assets.[10]

The French government was also forthcoming about the strategic security threat Mali posed to France itself should the so-called Islamist groups become dominant in the country.[11] With France’s interests at heart, the French defence minister said (in November 2012) “In Mali, it is our own security that is at stake … because if we don’t move a terrorist entity will take shape which could hit … France.”[12] An intervention driven by goodwill would be an anomaly since “there have been many worse atrocities in other former French African colonies, and such a heavy-handed response [had] not been forthcoming in those scenarios.”[13] In fact, the intervention has resulted in a greater sense of tension between Mali’s numerous ethnic groups, particularly with the Mali regime’s attacks against Tuareg and Fulani populations.[14] This period of Mali’s history will merely feed into its underlying ethnic problems, thus opening the country to greater risk of internal conflict and instability in the near future.

Whilst preparing for Mali, France refused to intervene in the Central African Republic (CAR), hence denying an elected government’s request for support against an expanding rebellion. In relation to this refusal the French President Francois Hollande said, “If we have a presence, it’s not to protect a regime, it’s to protect our nationals and our interests and in no way to intervene in the internal business of a country, in this case the Central African Republic.”[15] In other words, the aim of French foreign policy is to preserve French interests first and foremost. However, Hollande omitted the reality that the pursuit of France’s aims in Mali directly resulted in the support of an illegitimate regime as well as interference in Mali’s internal affairs. Nonetheless, it is clear that humanitarianism and goodwill do not sit as major priorities for France, neither in word nor in action.

Despite the illegitimacy of Mali’s ruling regime and its susceptibility to committing abuses against civilians, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) unanimously accepted the regime’s request in October 2012 for support against the rebellion in the North.[16] In effect, the UNSC approved the legality of the mission, and mandated that necessary military preparations be made.[17] It is intriguing that in a matter of months the request of an illegitimate regime was granted alongside prompt military support. Yet, decisive humanitarian support for Syria has repeatedly succumbed to disagreements within the UNSC, despite the urgency of the situation and the open-brutality of the Assad regime.

Given these realities, one will find little reason to assume that the main objective of the French-led intervention is to guarantee the well being of the people of Mali. The emerging future for Mali is increasingly one of greater ethnic conflict, greater instability, and greater hardship for the population.

[1] Simon Allison. “Mali: five key facts about the conflict.” The Guardian. 22 January 2013. Available at:

[2] Tim Whenwell. “Witness describes Mali forces ‘executing’ students.” BBC Newsnight, Mali. 31 January 2013. Available at:< http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-21283829>

[3] Whenwell

[4] “Islamists use fear, drug money to maintain control of northern Mali – UN rights official.” UN News Centre. 10 October 2012. Available at:

tCso5di>

[5] Applebaum.

[6] Robert Fisk. “Algerian Hijack: France Supplies Covert Military Aid to Regime: the Deals” The Independent. 27 December 1994. Available at:

[7] Roula Khalaf. “France regrets misjudgement over Ben Ali.” Financial Times. 18 January 2011. Available at:

[8] Mwangi S. Kimenyi and Brandon Routman. “The Second Coming of France in Mali and the Challenges of Continental Leadership in Africa.” The Brookings Institution. 18 January 2013. Available at:

[9] Kimenyi and Routman.

[10] Steven Erlanger. “France Is Increasing Security at Sites in Niger and at Home.” The New York Times. 24 January 2013. Available at:

[11] Kimenyi and Routman.

[12] Kimenyi and Routman

[13] Kimenyi and Routman.

[14] Afua Hirsch. “Mali’s army suspected of abuses and unlawful killings as war rages.” The Observer 19 January 2013. Available at:

[15] Paul-Marin Ngoupana. “Central African Republic appeals for French help against rebels, Paris balks.” Reuters 27 December 2012. Available at:

720121227>

[16] Resolution 2071 (2012). “Security Council Demands that Armed Groups cease Human Rights Abuses, Humanitarian Violations in Northern Mali.” United Nations: Department of Public Information. 12 October 2012. Available at:< http://www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2012/sc10789.doc.htm>

[17] Resolution 2071. UNSC.

0 comments

Anonymous

9th February 2013 at 3:54 pm

may allah swt give hidaya to muslims n their leaderz ,,ameeeeeeeen